Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PUZZLES AND DELIGHTS

ARCHITECT FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT continues to puzzle and delight. He designed a building to celebrate flat objects with nary a flat wall, yet it functions splendidly. He defined an office setting that not so subtly differentiated administrators from their staffs, but it’s considered a masterpiece of business architecture. He devised brilliant constructions that appeal to the eye, yet frustrate other human senses.

Here are a few tidbits I gleaned from several sources that celebrate these puzzles and delights of Frank Lloyd Wright.

In designing the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, FLW completely reassessed the concept of displaying art. His idea was to avoid the traditional interconnected series of rooms that required visitors to retrace steps past objects already seen.

Rather, FLW designed a gradual descending spiral surrounding a central atrium. Visitors take an elevator to the top, then leisurely return to ground level while admiring the art and ambience of the structure.

The Guggenheim’s spiral walkway, seen from across its atrium. Image from Wallygva at English Wikipedia.

FLW’s design puzzled more than few. Wouldn’t the building overwhelm the artworks? Wasn’t it awkward to hang paintings, flat objects, after all, on concave walls that slanted outward in low-ceilinged chambers?

In fact, prior to the Guggenheim’s opening in 1959, 21 artists signed a letter protesting display of their works in such a setting.

Today, the Guggenheim is considered a landmark of 20th century architecture. Only the largest paintings are confined by its nine-foot eight-inch high ceilings. And other museums, for example, the BMW Museum in Munich and the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart have emulated its spiral walkway.

Like others of his projects, the world headquarters for Johnson Wax in Racine, Wisconsin, was envisioned as a totality: architecture, internal layouts, even furniture and accessories. As an example of this unity of design, FLW’s beloved Cherokee Red color is evident in exterior brickwork and interior decor.

The Great Room of Johnson Wax headquarters features FLW-designed desks and chairs, and plenty of Cherokee Red.

The headquarters’ Great Workroom is an open office layout originally intended for secretaries; administrators resided in a surrounding mezzanine. Further to differentiate their roles, the executive office chairs are four-legged; secretary chairs have only three.

Above. a secretary work station. Image from 50 Favorite Furnishings by Frank Lloyd Wright, by Diane Maddex. Below, an administrator’s chair miniature ($250), next to a Robie chair ($189), a Peacock/Imperial Hotel chair ($275) and fountain pen. Image and products from Frank Lloyd Wright Gallery, marshallfields.com.

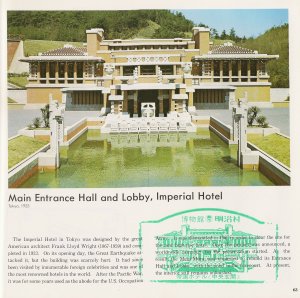

I dearly admire FLW’s Imperial Hotel Tokyo. Indeed, I’ve visited its recreation at the Museum Meiji-Mura about 20 miles north of Nagoya, Japan.

The Imperial’s Meiji-Mura recreation includes its lobby and mezzanine tea room. Artful though they are, its Peacock/Imperial Hotel chairs were not all that comfy.

Above, the Imperial’s mezzanine tea room. Below, its Peacock/Imperial Hotel chairs. Image from 50 Favorite Furnishings by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Whereas I dearly admire FLW’s Imperial Hotel Tokyo, I positively lust after his Taliesin 2 Floor Lamp. Conceived in 1914, and returned to over the years, this design has its bulbs contained in cherrywood boxes reflecting light off panels mounted to its vertical pedestal.

Above, Taliesin 2 Floor Lamp, 1951 ($2530). Below, a variation in the Lovness Dining Room, 1972. Images from 50 Favorite Furnishings by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Taliesin 2 is tall, 80 1/8-inches, and delivers what the Frank Lloyd Wright Gallery calls “broken geometric patterns like moonlight through the leaves of a tree…” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2016

FLW for all his aesthetic inspiration was a dangerous architect if you recall the house that cantilevered over the waterfall. Supposedly the fellow contracted to build it, though not a qualified structural engineer feared it was inadequately supported. He roughly doubled the sections of the support members at considerable disagreement with Wright. And even so, the thing sagged into uselessness and needed shoring up at great expense.

For some reason, many of his buildings had roof problems. After many years of leaks, for instance, the Marin Co. (Calif.) Civic Center had to be nearly completely re-roofed at great expense using a redesigned system. Beautiful, but not always practical.

Remember his answer to the fellow complaining about the leak onto his desk: “Move the desk.”

It reminds me of the comment attributed to Ettore Bugatti about his cars’ cable brakes: “I make my cars to go, not to stop.”

A more recent “top-down” museum experience is the Petersen Automotive Museum in its current incarnation at Wilshire and Fairfax in Los Angeles. They did not start from scratch though, so it’s the “helical” stairway (I have been told, “do NOT call it a ‘spiral’ stair!”) that carries you from the 3rd floor (“History”) to the 2nd (“Industry”) and at last to the 1st (Art). The elevators that take you to the 3rd floor to begin your tour are the original Hitachis from the 1962 Seibu Department Store that still constitutes the bones of the building. The labels have been removed, so perhaps they withdrew their endorsement.

A good point, helical versus (expanding or contracting) spiral. I’ll have to remember this.