Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

CELEBRATING 100 YEARS OF ART DECO PART 1

READERS OF SIMANAITISSAYS MIGHT HAVE CAUGHT ON that I love Art Deco: See, for example, “Deco Dreaming,” “Soaring Art Deco—In The City of Angels,” and even, lamentably enough, “Art Deco, The Met, The Polish Brigade, Trump Tower, And Truth.”

And what better time to celebrate this 20th-century sleek techo style than its 100th anniversary: In BBC History, August 2025, Emma Bastin offers “Designs for Life.” In Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, we glean tidbits from Bastin’s views on the Art Deco genre.

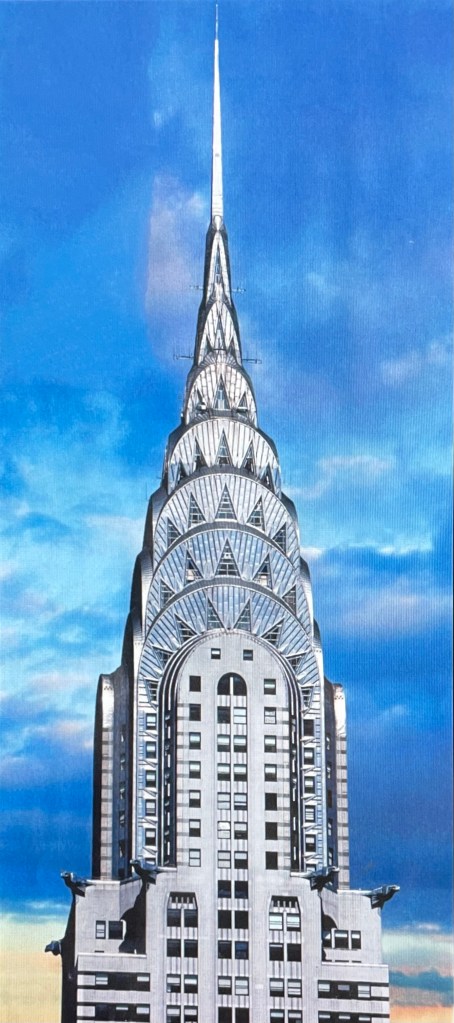

The Chrysler Building, New York City, William Van Alen, 1930. This, the following images, and occasional captions from BBC History.

The Name Comes Late. Emma Bastin observes, “Art Deco—a shortened, anglicised version of arts décoratifs—was never referred to as such in its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s. Like most art movements, it gained its name long after its popularity had waned. The first use of the term as we use it now was by art historian Bevis Hillier in 1968.”

Hitherto, according to Wikipedia, the genre had been known as Art Moderne. These days, this latter term is reserved to describe the later streamlined style of Art Deco in the 1930s.

A Response to its Times. “Art Deco,” Bastin recounts, “was a response to the social, cultural, and economic climate in which it emerged. It drew inspiration from a diverse range of sources, from ancient Egypt to the avant-garde, incorporating motifs from nature as well as concepts of mass-production using artificial materials.”

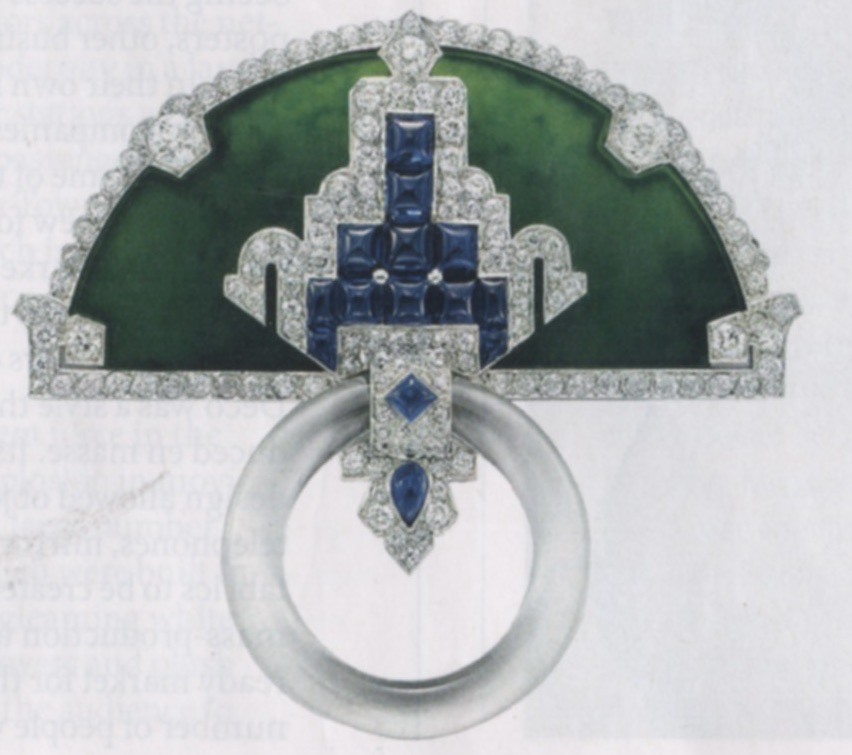

This Cartier brooch, c. 1925, “has a jadeite background showcasing diamonds and sapphires set in a geometric design.”

The 1925 Paris Expo. It was seven years after “the war to end all wars.” Bastin writes, “Unsurprisingly, advances in art and design were temporarily halted during the war but quickly leapt forward in the following years, driven largely by the desire to forget—to make a break with what had gone before—and for modernity”

Picture Palaces. “Cinema,” Bastin notes, “proved to be a potent force in the spread of Art Deco…. From their gleaming white exteriors to their modern foyers and plush interiors, cinemas allowed the audience to lose themselves in fantasy for a few hours.”

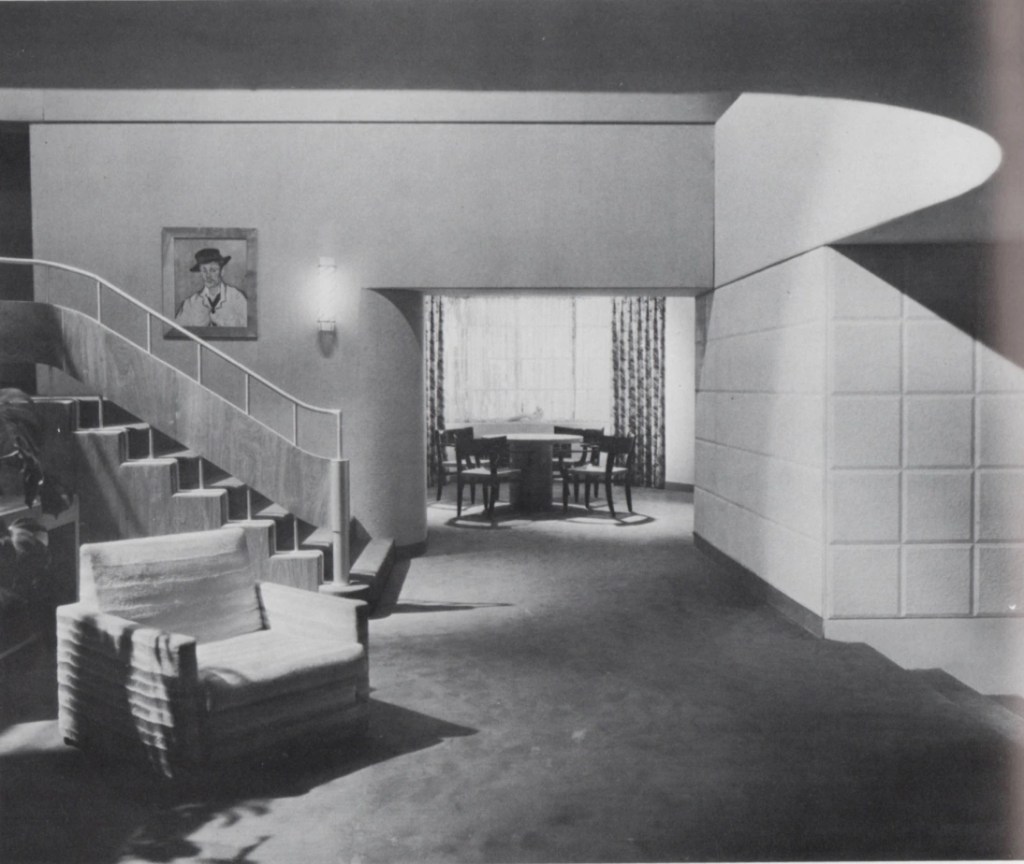

Bastin observes, “It was not only the cinema buildings that were Art Deco: the films themselves were also heavily influenced by the movement. From the 1920s, the industry led the way in fusing modernity and glamor. Hollywood art director Cedric Gibbons, who visited the 1925 expo, became the master of Art Deco styling in films.”

A scene from After the Thin Man, 1936. Supervisory Art Director: Cedric Gibbons. Image from “Deco Flicks.”

Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll explore Art Deco’s need for speed, distinctive style, and marketing to the masses. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Art Deco not only influenced buildings and jewelry of the day, but fashion in dress and wonderful advertising art … of all types. Planes, trains and boats of all sizes were influenced, and portrayed in many of the more collectable posters and movie lobby displays.DeHavilland and most French airplanes fairly screamed Deco, as did most sleek ocean liners, with coach builders going wild on Cords, Bugattis, and every long and svelte aspirational dream on wheels.The PBS “Poirot” mysteries seek out remaining architectural, fashion and motive examples to celebrate in their episodes.