Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

RADIO FOLKS IN THE MOVIES

GIVEN MY DUAL APPRECIATION OF old-time radio (via SiriusXM “Radio Classics”) and old-time movies (via Turner Classic Movies), it’s not surprising that I find occasional delight in the latter containing personalities from the former. Here are tidbits gleaned from one place and another, each a different variation on this theme.

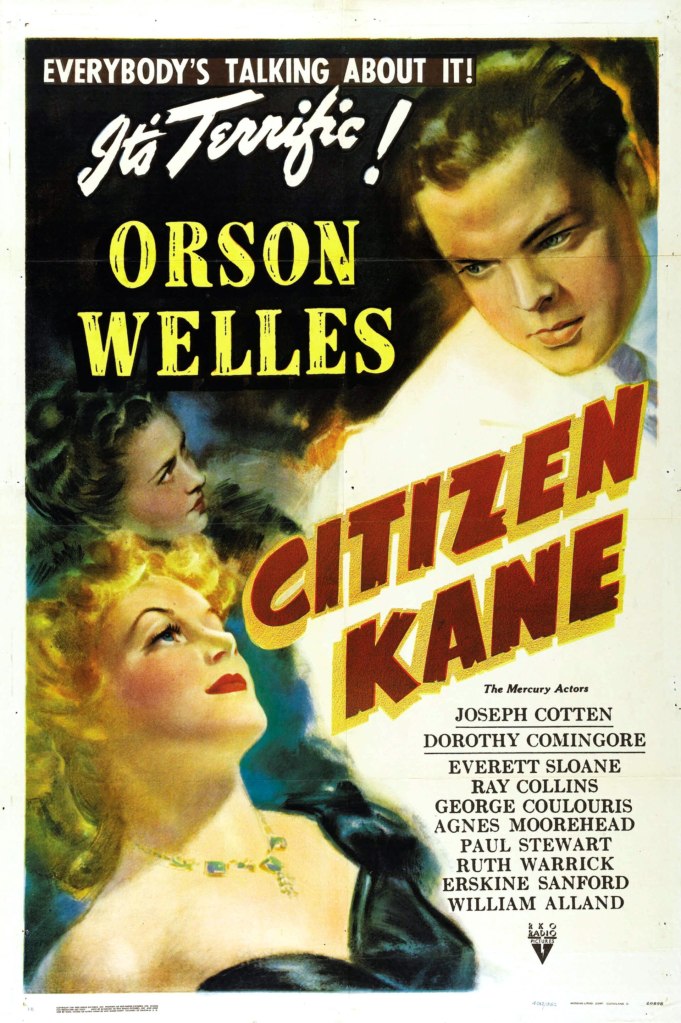

A Polymath at Work. Orson Welles’s professional career began in 1931 at Dublin’s Gate Theatre into which he conned his way as an alleged Broadway star. Back in the U.S. he got his first radio job in 1934. Within a year, Wikipedia notes, “he was earning as much as $2,000 a week, shuttling between radio studios at such a pace that he would arrive barely in time for a quick scan of his lines before he was on the air.” He optimized his Manhattan gig-to-gig commuting by doing it in a rented ambulance.

Welles’s theatrical endeavors at the time included the Federal Theatre Project, finally closed down by Congressional criticism. SimanaitisSays noted, “One of its ironies was a Congressional objection to the musical Sing for Your Supper; this, despite its patriotic finale, ‘Ballad for Americans,’ being chosen as theme song for the 1940 Republican National Convention.”

“Fat lot of good it did them,” the website continues. “Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt carried 38 states to Republican Wendell Wilkie’s 10. Orson Welles’s career, though, was only beginning. He was 25; Citizen Kane was a year away.

“Citizen Kane,” notes Wikipedia, “is frequently cited as the greatest film ever made.” Other films displaying his polymath capabilities included The Stranger (1946); noir favorites of mine The Lady from Shanghai (1947) and Touch of Evil (1958); also Chimes at Midnight (1966); and the quirky essay film F for Fake (1973).

Rochester’s Starring Role, Sorta. Eddie Anderson is best known as Jack Benny’s foil/sidekick/valet Rochester. Rather more obscurely, he’s also known for “What Do Clark Gable and Eddie ‘Rochester’ Have in Common?”

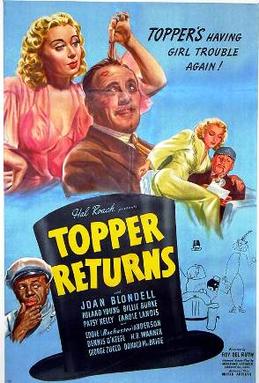

And also as a semi-starring role in Topper Returns. This 1941 supernatural comedy/murder mystery was a followup to Topper (1937) and Topper Takes a Trip (1938).

The Topper series exploited the whimsy of mousy banker Cosmo Topper having the ability to see and speak with ghosts. In Topper Returns, Eddie Anderson portrays his chauffeur (driving a 1937 Mercedes-Benz SSK!).

The 1937 Mercedes-Benz SSK in Topper Returns.

Eddie also recurs in a spooky-mansion routine with an easy chair flipping, a drop into a lagoon, and a pesky seal intent on retaining its top billing. The film is entertaining and deserves its Academy Awards nominations for Best Special Effects and for Best Sound Recording.

Purpose-Built Flicks. Several of these movies were designed specifically for radio personalities to portray characters on the screen, often playing themselves. Here We Go Again (1942) is typical of the genre, itself a followup of Look Who’s Laughing (1941). Both feature radio’s Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Jim and Marian Jordan (Fibber McGee & Molly), and Harold Peary (The Great Gildersleeve, itself a spinoff of the latter).

Wikipedia notes that both “provided needed profits for the beleaguered studio. The film historians did identify the main failing of Here We Go Again, ‘Faced with dreaming up a story that would make use of the various comedians and other divergent talents, [writer] Paul Gerard Smith gave in to his most preposterous impulses, which was just fine with audiences….”

An Uncredited Appearance. The plot of Broadway Melody of 1936 is pretty thin, though it was nominated for Academy Award for Best Picture (Mutiny on the Bounty won). Wikipedia recounts, “Irene Foster (Eleanor Powell) tries to convince her high school sweetheart, Broadway producer Robert Gordon (Robert Taylor), to give her a chance to star in his new musical, but he is too busy with the rich widow (June Knight) backing his show…. Things become complicated when she begins impersonating a French dancer, who was actually the invention of a gossip columnist (Jack Benny, parodying Walter Winchell).”

A screen grab of Don Wilson in Broadway Melody of 1936.

Don Wilson, the regular announcer on The Jack Benny Program, is not credited in the flick, but his voice is evident to radio fans at the beginning—portraying a radio announcer.

A Double Whammy. Having mentioned Jack Benny’s (no better than lame) Winchell character in Broadway Melody of 1936, I note the radio-to-screen-back-to radio double whammy of his The Horn Blows at Midnight.

Wikipedia observes, “Following its poor box-office [budget: $1,831,000; box office: $970,000], Benny often exploited the film’s failure for laughs over the next 20 years in his radio and television programs, making the film a known entity to his audience, even if they had never seen it.”

It isn’t all that bad, though I believe its subsequent radio jokes are better: A struggling theater owner rents out seats to a mortuary’s clientele, and tells Benny even they walked out. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024.