Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

PAUL FRÈRE ON FERRARI PROTOTYPES 1961–1967 PART 2

YESTERDAY, WE BEGAN SHARING PAUL FRÈRE’S INSIGHTS gleaned from Cars in Profile Collection 1. Here in Part 2, Paul recounted Ferrari’s achievements as well as foibles.

Ferrari’s Initial Views on Fuel Injection. Paul recounted, “… when the fuel-injected Vanwalls were making Ferraris eat their dust in 1958, I remember him telling me, in one of many conversations I had with him, that ‘if all cars had had fuel injection up to then and someone suddenly came up with a carburetor, everyone would marvel at its simplicity and efficiency.”

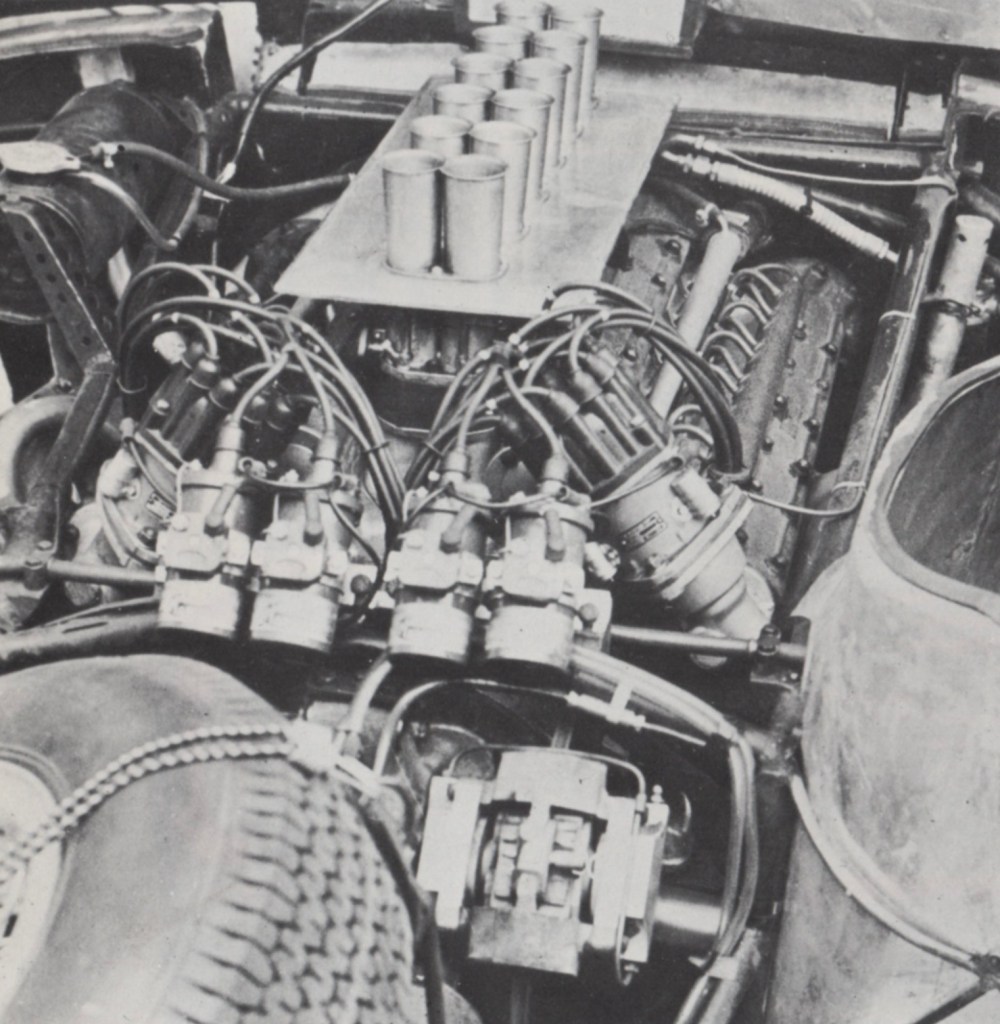

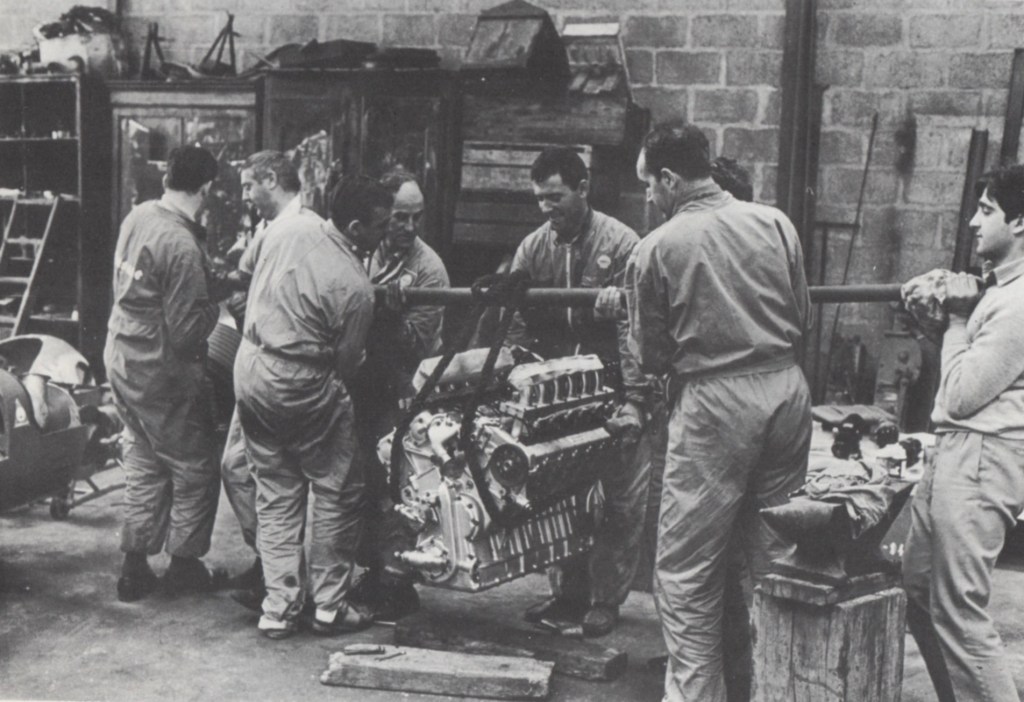

Above, the 1966 Ferrari 330 P3 V-12 engine. Below, preparing a 330 P4 engine for installation, Le Mans 1967. Both images by Geoffrey Goddard. These and following images from Cars in Profile Collection 1.

And on Engine Placement. Paul continued, “It also took him a long time to realize that in a racing car, the more logical place for the engine is behind the driver, just as for a long while he dismissed proper aerodynamics as ‘something he would leave to those people who were unable to muster adequate horsepower.’ ”

I am reminded of Ettore Bugatti’s response to an owner complaining about inadequate braking: “I build my cars to go, not to stop.”

Nevertheless, Times—and Thinking—Change. Ferrari won the 1962 Le Mans with the 330 TRI/LM Spyder, a front-engine V-12 car driven by Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien. The 1963 Sebring 12-hour, Nürburgring 1000-kilometer, and Le Mans 24-hour were won by the 250 P, a car with its V-12 located behind the driver.

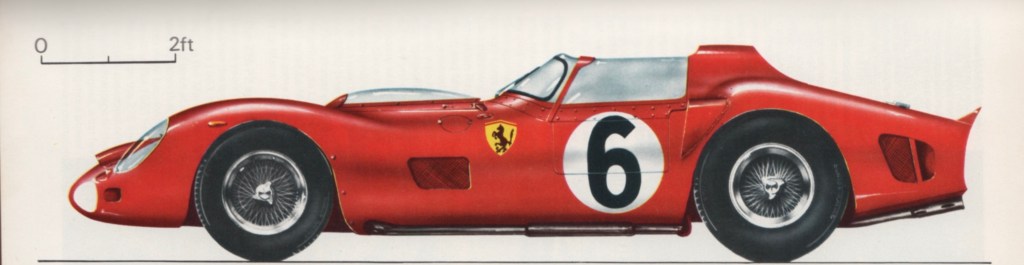

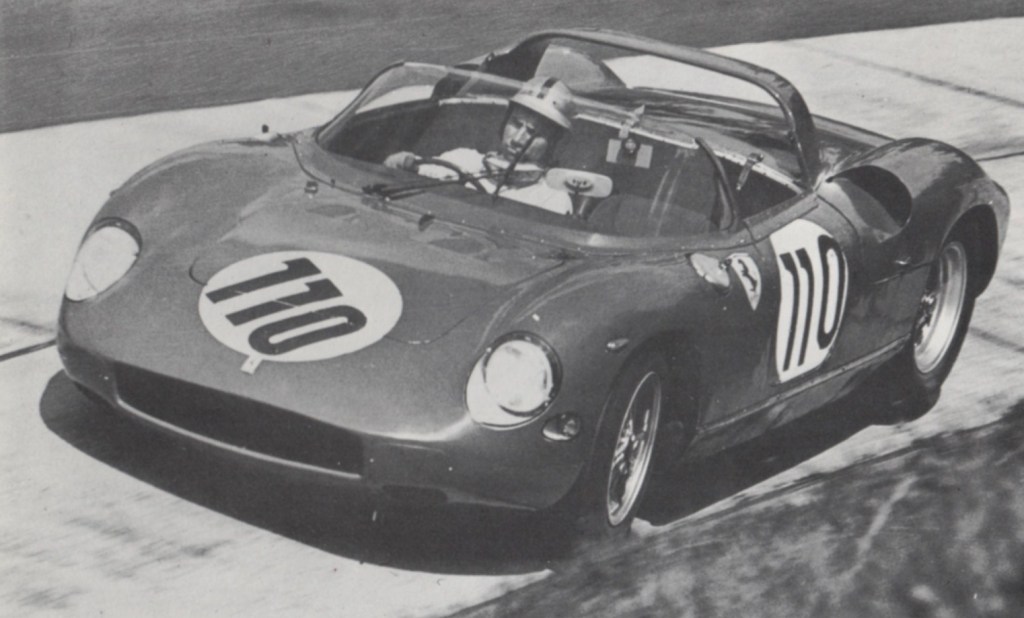

Above, the 1962 Le Mans-winning front-engine 330 TRI/LM Spyder. Image by Martin Lee. Below, a year later the 1963 Nürburgring-winning mid-engine 250 P. Image by Motor & Geoffrey Goddard.

The 330 TRI/LM displays the oddity of its embedded windscreen, one of many regulated changes after the horrific 1955 Le Mans disaster. The 250 P is, to my eye, one of the most pleasing sports prototypes ever.

Sister car of the Nürburgring-winning 250 P, its aerodynamic bread basket handle in prominent view. Image by Motor and Geoffrey Goddard.

Ferrari Jargon. The Cars in Profile analyses offer a glossary of the marque’s nomenclature: Since the start of Ferrari production, V-12 models have typically been identified by the unit capacity of a single cylinder: For example, the first production car, with total displacement 1500 cc, was a Tipo 125 (125 x 12 = 1500).

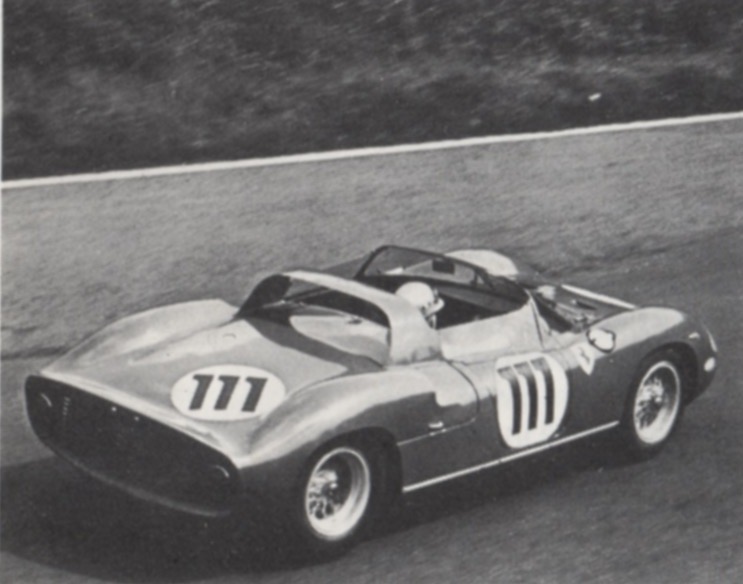

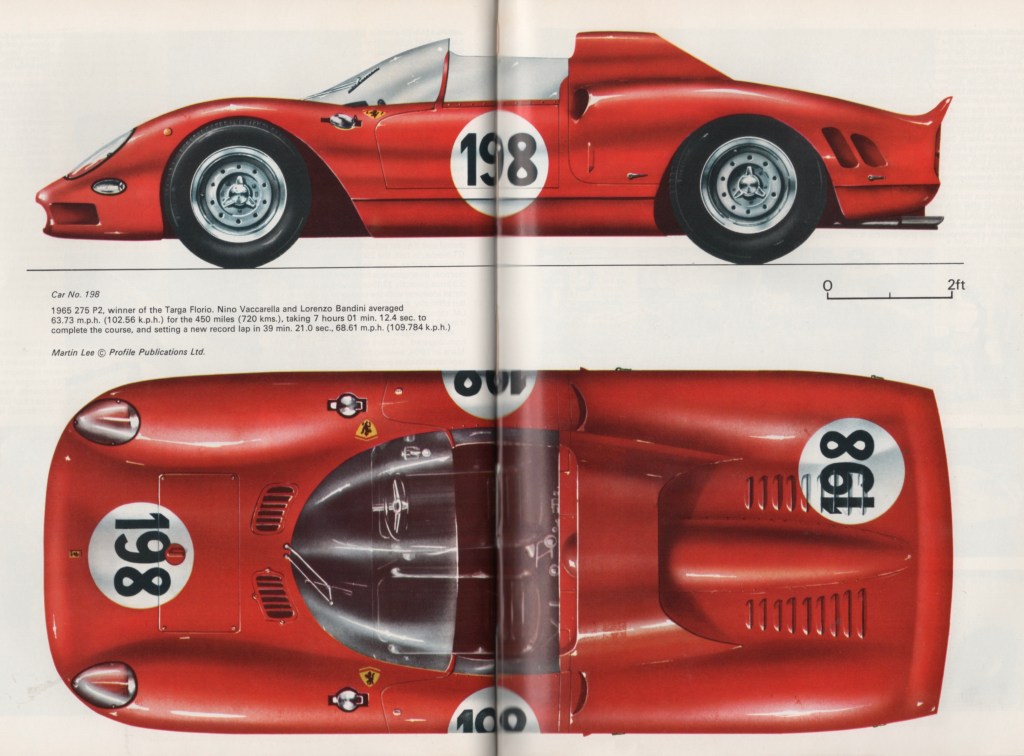

The 1965 Ferrari 275 P2, winner of the Targa Floria that year. Image by Martin Lee. (Displacement actually 3285 cc.)

With V-6 and some V-8 models, the first two figures suggested the total capacity and the last figure the number of cylinders: 246, for example, stands for 2.4 liters displacement of a V-6.

Alphabetical suffixes included S = Sport, P = Prototype, GT = Gran Turismo, LM = Le Mans, LMB = Le Mans Berlinetta. Nomenclatures could be combined, for example, with the 330 TRI/LM translating into a 4-liter V-12 with Testa Rossa (Red Head) cylinder heads and independent rear suspension as raced at Le Mans. The 250 GTO earned its originally handwritten O for “Omologato,” i.e, FIA-homologated.

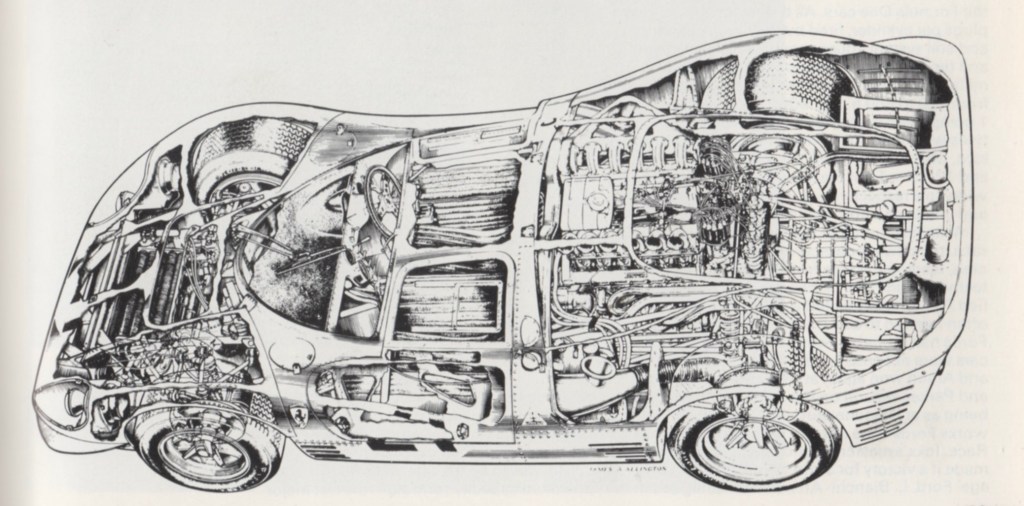

Complexities of the 330 P4—the most advanced of the Ferrari sports-racing prototypes. Image by Shell Oil.

Summary of 1961-1967. Paul recounted, “The period under review, 1961 to 1967, is the more interesting because it covers the years when Ferrari who had regained his dominance of Formula One as soon as he swopped over to the rear engine layout… and realized that even for two-seater prototypes it would be beneficial to have the engine behind the driver.”

And by then Ferrari had an entirely new challenger—the Ford Motor Company. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026

Tipo by cylinder capacity; interesting. Presumably, power varied by cylinder count (was there anything other than 12s at the time?) and supercharging within a given tune.

In a totally different context, Electro-Motive (later GM, now Progress Rail) did that with their locomotive diesels (starting in the 1930s): the original was the “567” line which was the individual cylinder capacity in cubic inches. Over the years, that grew to 645 then 710. Power varied by cylinder count (6 to 20), turbocharged or not, and various other settings.

If you are missing any magazines, e mail me.Years ago I gave Auto Week around 20 of ones they did not have.Enjoy looking at your “old articles”.Found the one about your visit to the Morgan factory and the 10 they made a day.Also found the letter to the editor exposing your numbers.Your reply, “AGG”John