Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

ON MATHEMATICAL PHILOSOPHIES

A CENTURY AGO, MATHEMATICIANS DEBATED THE EXISTENCE of numbers. “You’d think, after millenniums, we’d have gotten that straight,” writes Jordan Ellenberg in The New York Times Book Review, November 23, 2025. “But it’s not that simple,” Ellenberg says, “as Jason Socrates Bardi explains in his new book, The Great Math War.”

The Great Math War: How Three Brilliant Minds Fought for the Foundations of Mathematics, by Jason Socrates Bardi, Basic Books, 2025.

Reviewer Ellenberg is professor of mathematics at the University of Wisconsin. Bardi has published two other books about the history of mathematics, The Calculus Wars and The Fifth Postulate, and other articles about modern science and medicine.

Here are tidbits gleaned from Prof. Ellenberg’s review and Bardi’s book, together with my usual sleuthing. Indeed, “the three brilliant minds” have already appeared here at SimanaitisSays: Georg Cantor in “You Can Count On Me—Or Maybe Not,” Bertrand Russel in “Thinking About Change,” and Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer in “Combed Coconuts Have Cowlicks.”

The Great War Spills Over. “In Bardi’s telling,” Ellenberg recounts (poo! a math pun), “it was only natural for mathematicians to feel anxiety that the centuries-old, apparently stable structures of mathematics might have obscure but fatal cracks; they’d just learned the same thing about their international political system.”

Ellenberg continues, “Mathematics is a human activity, and the idea that mathematical reasoning can be fully separated from the rest of our lives is a fantasy. Bardi is very good at showing how the exclusion of German mathematicians from international conferences, long after the war’s end, created resentment that bled into the way scholars treated one another’s theories.”

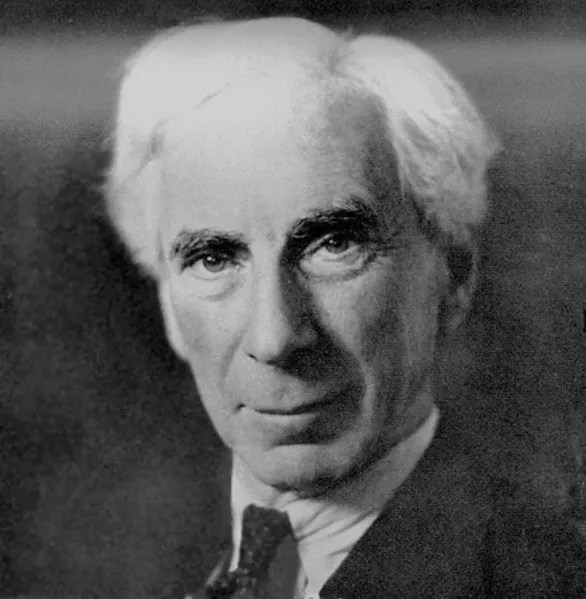

Paradoxes—in Math and in Life. Ellenberg cites, “Bertrand Russell, who came up with some of the first paradoxes that threatened math’s basic structure, is especially well drawn. Russell was torn between his respected academic research and his mostly hated work as an antiwar activist. He was also constantly involved in one love triangle or another. Most were sexual, but the one most movingly rendered here is composed of Russell, his lover Ottoline Morrell and the young Ludwig Wittgenstein—whose stormy relations with Russell were about math only.”

Bertrand Russell, 1872–1970, English philosopher, writer, mathematician, social critic, political activist, Nobel Laureate in Literature, 1950. Photo from 1938.

“For anyone who has admired Russell’s cool, heady philosophical writing,” Ellenberg observes, “it’s bracing to see that his personal life was a hot mess.”

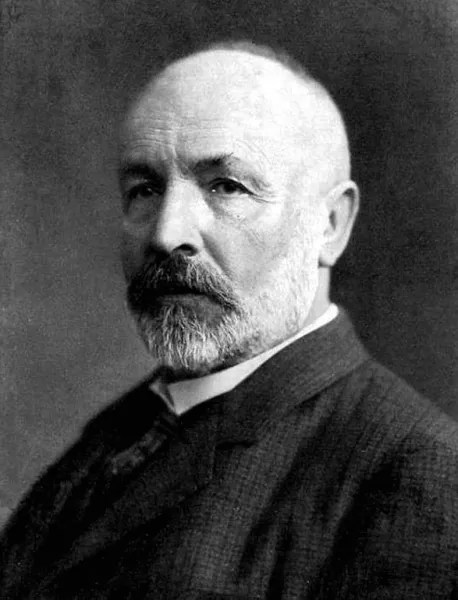

Cantor’s Many Infinities. “In the late 19th century,” Ellenberg notes, “Georg Cantor had proved, startlingly, that there wasn’t just one kind of infinity, but infinitely many kinds. And the infinity of the set of real numbers, while relatively modest, was not the very smallest. Numbers are complicated!”

Georg Cantor, 1845–1918, German mathematician, discoverer of set theory and of the uncountability of the real number line.

“Cantor’s theorem,” Ellenberg cites, “shows that the infinity of describable numbers— such as 3/25, or ⅙—is much, much smaller than the infinity of all real numbers.” Yet, Ellenberg notes, “There are numbers we simply cannot describe. Can you give an example? By definition, no. If that makes you uneasy, great. It made everybody uneasy.”

Brouwer as an Intuitionist. Ellenberg introduces a third “general in Bardi’s war”: “L.E.J. Brouwer advocated a radical solution: According to him, and to the ‘intuitionists’ who shared his views, the only things that are real in mathematics are things human beings with a finite life span can describe, and the only things that are true are those that admit a proof of finite length.”

Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer, 1881 – 1966, Dutch mathematician, a proponent of intuitionism, as opposed to mathematical formalism.

Ellenberg describes, “His opponents, [the formalists] chiefly represented here by the German mathematician David Hilbert, thought such a restrictive view gave away too much—throwing out most of the points on the number line, for instance.”

Intuitionism vs Formalism. Curiously (what with all the bitching I’ve done), Googling “Intuitionism vs Formalism” gives a cogent A.I. Overview of the two: “Intuitionism views mathematics as a product of the human mind, where truth requires a mental construction, while formalism sees mathematics as a formal system of symbols and rules, with truth determined by the consistency of the system, independent of human intuition.”

Without Trashing Either: We formalists enjoy mathematics as a game of symbols and rules. A mathematical statement is purely syntactic; it acquires application only with an interpretation.

I’m reminded of our purist grad school joke about doing applied math only with your office door locked.

Revisiting a Century-Old Controversy: Ellenberg concludes, “This dispute was not settled a hundred years ago, and it probably won’t be now. But in uncertain times, there’s value in remembering that we have been in a place like this before.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Related

Information

This entry was posted on November 28, 2025 by simanaitissays in Sci-Tech and tagged "Can Math Be Violent? For Three Scholars The Answer Could Be Yes" Jordan Ellenberg "New York Times Book Review", "The Great Math War: How Three Brilliant Minds Fought for the Foundations of Mathematics" Jason Socrates Bardi, Bertrand Russell "Thinking About Change", David Hilbert Formalist philosophy of mathematics, Georg Cantor "You Can Count On Me--Or Maybe Not", Jordan Ellenberg reviews Bardi's book "The Great Math War" "The New York Times Book Review", L.E.J Brouwer "Combed Coconuts Have Cowlicks", math philosophies: intuitionist vs formalist.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-kAeCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012