Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

INDEPENDENCE FOR WHOM? PART 1

A FEW DAYS AGO, I PROMISED to continue with more from The Atlantic’s “The Unfinished Revolution.” As I noted, think of this magazine’s excellent series as “a much appreciated (and much needed) civics lesson.”

Here, in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, are tidbits gleaned from Annette Gordon-Reed’s “Whose Independence?,” The Atlantic, October 9, 2025.

The American Creed. Annette Gordon-Reed recounts Thomas Jefferson’s challenge in drafting The Declaration of Independence: “He had to explain in both philosophical and legal terms the Second Continental Congress’s decision to break away from Great Britain, provide a list of grievances against the Crown that justified complete separation as a remedy, and plant the seeds of diplomacy for the fledgling country.”

“In the course of writing a document capacious enough to do all of that,” Gordon-Reed writes, “Jefferson formulated the Declaration’s second paragraph, with language that has become its most quotable passage: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ Those words, now held as perhaps the world’s most important statement of universal human rights, were so powerful that they are often described as the ‘American creed.’ ”

Declaration of Independence, by John Trumbull. The painting, oil on canvas, 12 ft. x 18 ft., was commissioned in 1817, purchased 1819, and mounted in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in 1826.

A Contradiction, a Challenge. Gordon-Reed observes, “But those words also created a glaring contradiction. Of the estimated 2.5 million people living in the American colonies, about 500,000 were enslaved people of African descent, the majority of whom lived in the southern colonies. About 200,000 lived in the largest colony, Jefferson’s Virginia.”

She continues, “At the time Jefferson wrote that part of the Declaration, he owned nearly 200 people at his home plantation, Monticello, and other sites. While working on the document in Philadelphia, he shared rooms with his enslaved valet, Robert Hemmings, the 14-year-old half brother of his wife, Martha.”

By the way, see Monticelllo.org with regard to Hemmings verses Hemings. Robert appears in The Atlantic’s three-page foldout of personages in “The Unfinished Revolution.” He’s standing in the middle, key no. 13. Also, see “Hurrrah for Mac ‘n’ Cheese (and History and Non-Binary Gender)” for another Hemmings member of the Jefferson entourage.

Gordon-Reed also describes Prince Hall, no. 14, directly behind and above Hemmings. Hall was a Boston colonial, founder of America’s first lodge of Black Freemasons and a noted antislavery activist.

Image by Joe McKendry from The Atlantic.

Artist Joe McKendry employed this contemporary portrait of Prince Hall. Image from The Atlantic.

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 1857. Through U.S. history, there have been glaring examples in contradiction of what Gordon-Reed calls “the core of American law and culture.”

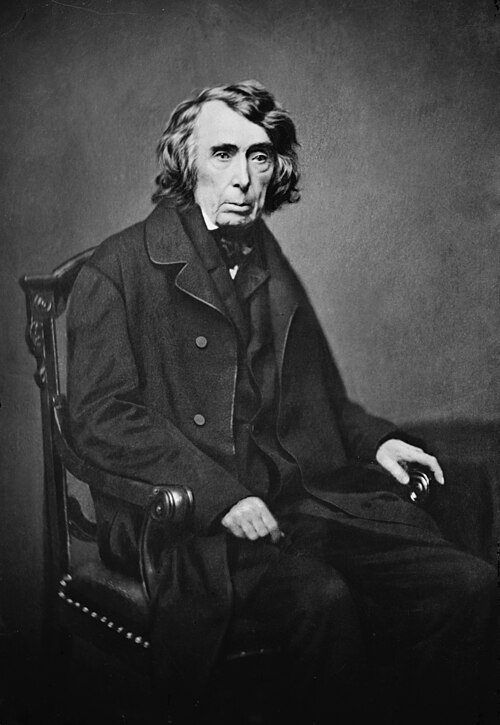

In discussing the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford, she writes, “The infamous 1857 ruling held that people of African descent were not citizens of the United States. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney looked to his version of history and found that ‘neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.’ ”

Note well, even free Blacks were included in Taney’s pronouncement. (?!)

Roger Brooke Taney, 1777–1864, American lawyer and politician, fifth chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, 1836–1864. Image by Matthew Brady, 1850.

“Taney’s issue, of course,” Gordon-Reed stresses, “was race. For him, being white was the basic requirement for being an American.”

I shudder in reading about Dred Scott v. Sandford, just as I do when learning of Trump’s refugee goals. What I recall from civics lessons of yore is “give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Tomorrow in Part 2, a civil war ensues and, in its conclusion, Annette Gordon-Reed observes, “the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to settle the matter.”

Would that it had been so simple. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

To think that even today, two and a half centuries later, we’ve yet to cleanse our national soul simply as the cradles of western democracy, Athens, and to a lesser extent, Rome, saw no irony in slavery. That glaring oversight was carried over when our founding fathers used Greek civic virtue, Roman republicanism, a senate, checks and balances, our public buildings following classical architecture, a century later the Statue of Liberty harking to Roman goddesses.

Washington followed Cincinnatus’s humility, even as John Adams’ Cicero’s eloquence, but Homer, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas accepted slavery, Immanuel Kant later justifying it on racial grounds.

At our founding, the United States of America was the not just the world’s only democracy, other than the Iroquoian Six Nations Confederacy, or republic, but truly neither, rather a melding of both. For all our hope and striving, racism and slavery yet along for the ride.

A long overdue step in the right direction would be the end of the Electoral College, which favored slave states.