Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

OTHELLOS AND IAGOS WE’VE LOVED AND HATED PART 2

YESTERDAY, BEN BRANTLEY’S PIECE IN THE NEW YORK TIMES got us started in Othellos and Iagos through time. Here in Part 2 we pick up with a complex relationship of people in a 1943 Broadway production of Othello.

Paul Robeson and José Ferrer, Broadway, 1943. Ben Brantley notes, “It took 13 years for Robeson’s singular, boundary-shattering brand of Shakespearean lightning to strike in Manhattan. But this production, astutely directed by Margaret Webster, was a more unconditional triumph. It helped that Ferrer’s Iago was, as Lewis Nichols put it in The Times, ‘a half dancing, half strutting Mephistopheles.’ (Desdemona was, if you please, Uta Hagen, Ferrer’s wife, who became Robeson’s lover.)”

Paul Robeson (Othello) and Uta Hagen (Desdemona) in the 1943 Broadway production. Image from the U.S. Library of Congress.

“At a time when anti-miscegenation laws were still on the books in the States,” Brantley writes, “there were worries that the interracial love affair might alienate audiences. But the opening-night ovations were again thunderous, and reviews were largely ecstatic. (The Herald Tribune described it as a ‘tribute to the art that transcends racial boundaries.’) The production broke records for a Shakespeare play on Broadway, clocking 296 performances.”

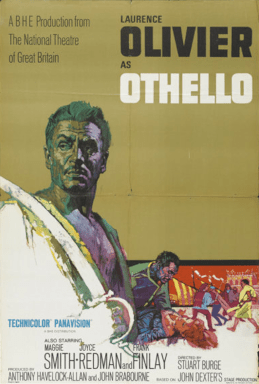

Laurence Olivier and Frank Finlay, London, 1964. Brantley recounts, “Those who saw Olivier’s Calypso-cadenced Moor onstage swear he was mesmerizing. His ‘power, passion and verisimilitude,’ wrote the critic in The Sunday Times of London, ‘will be spoken of with wonder for a long time to come.’ ”

The theatrical poster. Image from Wikipedia.

However, Brantley noted, “But captured on film the next year, Olivier’s blackface makeup and exaggerated mannerisms registered as grotesque and, to many, deeply offensive. A university professor recently discovered it was not a film to show latter-day students.”

Jake Gyllenhaal and Denzel Washington in the play’s latest revival, on Broadway through June 8, 2025. Image by Sara Krulwich/The New York Times.

Orson Welles and Others “Making Down.” Plenty of Othellos were played in blackface. Not cited by Brantley was Orson Welles’ Federal Theatre Project and its “Voodoo Macbeth.” Staged as part of the New York City Negro Theater Unit in 1936, an all-Black cast set the Shakespeare classic in Haiti.

Macbeth with the Three Witches, Orson Welles’ “Voodoo Macbeth.” Image from Wikipedia.

In Barbara Leeming’s Orson Welles: A Biography, she recounts lighter-skinned Black actors “making down” (i.e., darkening their complexions). Indeed, they joked with Welles in doing so when he stood in for an ailing cast member.

Later, by the way, Welles portrayed Othello in his 1951 film, an adaption of the play. Wikipedia notes this was one of Welles’s more complicated shoots, filmed erratically over three years. His original producer went broke. Pouring his own money into the project, Welles would suspend production while he raised cash taking part in others’ films.

A good tale in this: “When Welles acted in the 1950 film The Black Rose, he insisted that the coat his character, Bayan, wore be lined with mink, even though it would not be visible. Despite the expense, the producers agreed to his request. At the end of filming, the coat disappeared, but could subsequently be seen in Othello with the fur lining exposed.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Related

One comment on “OTHELLOS AND IAGOS WE’VE LOVED AND HATED PART 2 ”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Information

This entry was posted on April 14, 2025 by simanaitissays in And Furthermore... and tagged "Othello and Iago a Marriage Made in Both Heaven and Hell" Ben Brantley "The New York Times", "Othello" Laurence Olivier in blackface 1964, "Othello" on Broadway through June 8: Jake Gyllenhaal (Iago) Denzel Washington (Othello), Barbara Leeming Welles bio: "making down" darkening the skin of Black actor, Orson Welles "Othello" lengthy production time (running out of funds), Orson Welles commissions mink-linked coat for "The Black Rose" used later in his "Othello", Paul Robeson Uta Hagen José Ferrer "Othello" 1943 (other complications).Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-jrxCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

I just realized that it’s been thirty years since I last saw Othello, in this case, the film starring Laurence Fishburne and Kenneth Branagh. The overwhelming tragedy of it all left me feeling disturbed.