Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

OTHELLOS AND IAGOS WE’VE LOVED AND HATED PART 1

CULTURAL NAIF I’VE ALWAYS BEEN (Moby-Dick is about this big whale), Shakespeare’s Othello is a good-guy Moor, albeit prone to jealousy and homocide; Iago is a bad-guy all-around-conniving ensign. Imagine then my reading Ben Brantley’s “Othello and Iago, a Marriage Made in Both Heaven and Hell,” The New York Times, April 1, 2025.

Ben Brantley writes, “Who exactly is in charge here? Is it the strutting general or his self-effacing ensign? The man celebrated for his ‘free and open nature’ or the sociopath who keeps stockpiling secrets?”

“On the most basic level,” Brantley continues, “the answer is obvious. (For those unfamiliar with “Othello,” serious spoilers follow.) It’s the resentment-riddled Iago, the ultimate disgruntled employee, who takes command of his commander, and pretty much everyone in his orbit, in coldblooded pursuit of revenge. It’s Iago who gives the orders to his boss, while making his boss believe otherwise. And it’s Iago who’s still alive at the end.”

Well, there is that.

“But in another sense,” Brantley says, “the contest has never been that easy to call. Put it this way: After you’ve seen it, who is it who dominates your thoughts? Which character’s point of view wound up ruling the night? In other words, who owned the production?”

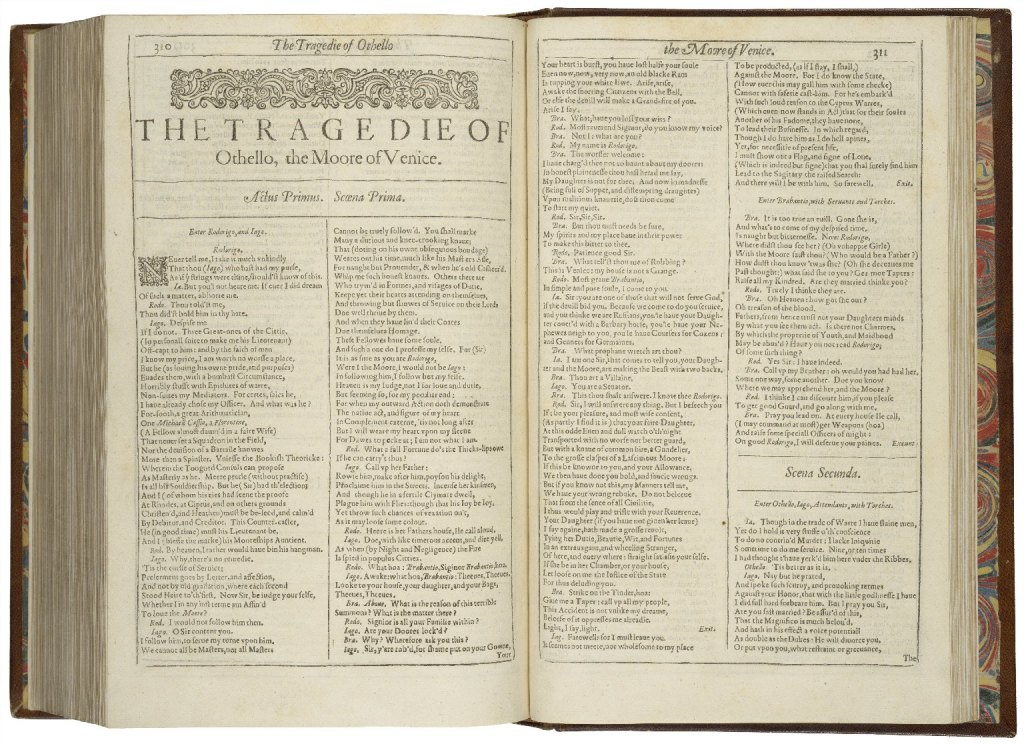

The first page of Othello from the the First Folio, printed in 1623. Image from Wikipedia.

Brantley then follows up with capsule commentaries of Othellos ranging from London, 1930, to Broadway, 2025. Here, in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, are tidbits gleaned from these various productions, together with personal reflections thereon.

Othello’s Tragedy, But Iago’s Play. Brantley observes, “ ‘Othello’ is Shakespeare’s only major work in which the hero and antihero are given equal weight. (If you keep score by monologues, Iago has eight of them; Othello only three.) And as the Shakespeare scholar Harold Bloom summed up the dichotomy: It is Othello’s tragedy, but it is Iago’s play.”

“There is another way, of course, in which ‘Othello’ is singular in Shakespeare,” Brantley recounts. “Its leading man is Black, and for centuries he was almost always portrayed by white men with dark makeup. And it is as impossible now to see ‘Othello’ without thinking of racism as it is to revisit ‘The Merchant of Venice’ without thinking of antisemitism.”

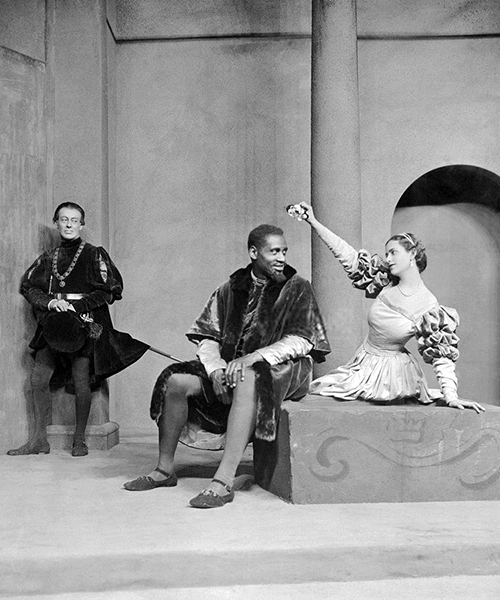

Maurice Browne (Iago), Paul Robeson (Othello), and Peggy Ashcroft (Desdemona) in Othello at the Savoy Theatre, 1930. Image from newyorkerstateofmind.com.

Paul Robeson and Maurice Browne, London, 1930. Brantley describes, “By all accounts, Robeson’s opening night at the Savoy Theater was one of those extraordinary evenings when an audience felt it had witnessed history in the making, and it ended in 20 curtain calls.… This was, after all, the first Black actor to appear on a mainstream London stage as Othello in nearly a century, when another American, Ira Aldridge, briefly took over from an ailing Edmund Kean.”

Indeed, Ira Aldridge has already made an appearance here at SimanaitisSays: He also portrayed Aaron in Titus Andronicus in London in 1852.

Tomorrow in Part 2, Brantley describes a real-life triangle involving Othello personages in 1943. And Orson Welles portrays a well-dressed Othello through skullduggery. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

I hope readers are able to seek out the audio recordings of Robson’s Othello. His power and troubled sensitivity will overwhelm you. His caged fury is evident, and it’s almost better than witnessing in person from the middle rows.