Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

POURING A CAT

ANY CAT LOVER KNOWS A FELINE’S AFFINITY for fitting itself into enclosures of any shape—and seemingly any size. AAAS Science addresses this in a scholarly manner in “How a Cat is Like a (Furry) Pancake,” September 19, 2024.

“Cats,” Science writes, “show a remarkable ability to squeeze under doors, cram themselves into vases, and wiggle through impossibly small holes. That may be because they sometimes don’t think about the size and shape of their own bodies, a study has found.”

Science continues, “Researchers placed rectangular holes in front of 30 felines that the scientists could narrow both widthwise and lengthwise. When the apertures shrank in height, the cats hesitated before trying to pass through. This suggests that, like dogs, they know how tall they are—something scientists call ‘body size awareness,’ which is linked to self-awareness in humans. But the felines showed no such hesitation when confronted with apertures the scientists narrowed in width, they write this week in iScience.”

Aspects of this research paper are noteworthy to me and my feline pal πwhacket: Our personal experiences (of trivial methodology compared to those reported in iScience) generally confirm this behavior. And, even more telling, πwhacket was highly amused to examine the responses of various test subjects.

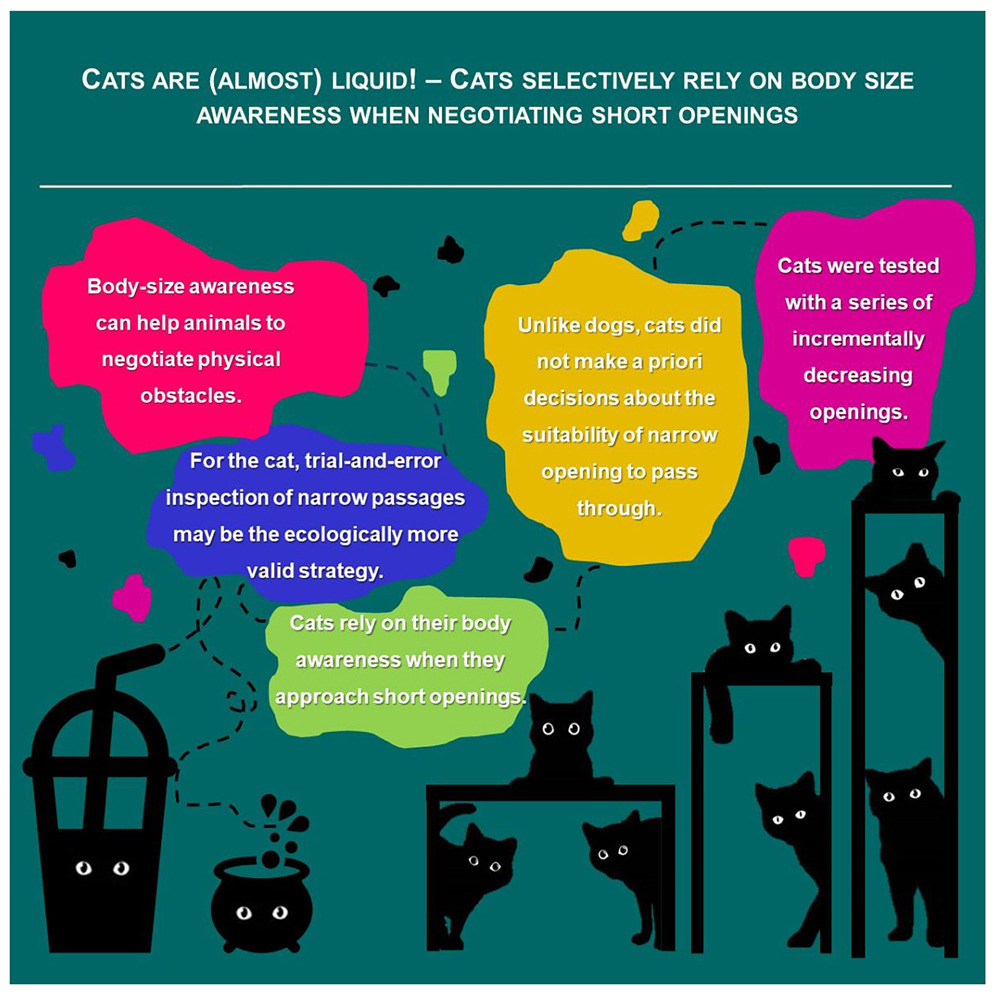

Here are tidbits gleaned from the Science item as well as from “Cats are (Almost) Liquid—Cats Selectively Rely on Body Size Awareness When Negotiating Short Distances,” by Péter Pongrácz, iScience, September 17, 2024.

Highlights. Pongrácz writes, “Cats were tested for their body-awareness with incrementally decreasing openings. Cats did not make a priori decisions when they approached tall, narrow openings. However, cats hesitated to approach and enter uncomfortably short apertures. Trial-and-error or body-awareness are both ecologically valid strategies for cats.”

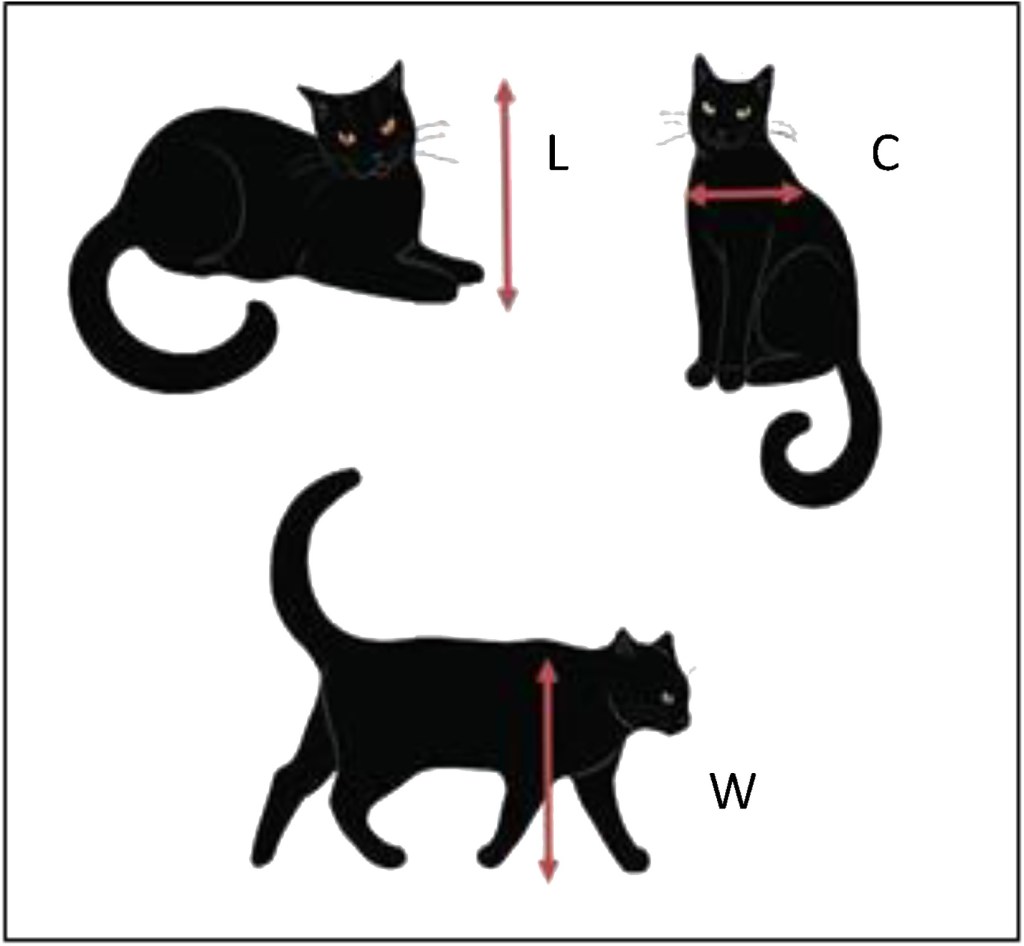

Average Test Subject. The average test subject measured 19.61 cm in “Sphinx posture;” 11.48 cm in chest width, and 27.97 cm at the withers. Its head width was 10.14 cm; its total height, paw to ear tip, was 37.12 cm.

L is height in laying (“Sphinx”) posture; C is width of chest; W, height at the withers. This and other images from Pongrácz, iScience.

My attempt at measuring π was a shambles. He kept nuzzling the steel ruler.

Methodology: “The cat is depicted in front of an opening of the cardboard panel (black), which is attached to a doorframe in the owner’s home. O = owner (behind the panel); S = start point; A = assistant (a family member, who was asked to position the cat, and release it from the start point); E = experimenter (who recorded the trials with her mobile phone camera).”

Schematic overhead of typical testing scene.

Methodology continues: “In some cases, when there was no assistant, the experimenter held the cat at the start point, and the camera was placed to a piece furniture, 1–1.2 m above the floor.”

I’m comforted to read that I’m not the only one challenged by methodology. Pongrácz reports, “Although we run the statistical tests on the composite behavioral variables, some of the original behaviors are worthy to report also as descriptive results. In the case of the ‘same height’ openings (Table 2), two cats opted for jumping over the panel, both in trial 4. In the case of the ‘same width’ openings (Table 3), one cat jumped over the panel in each trial, three cats jumped over the panel in trial 4, one cat jumped over in trials 4–5, one cat jumped over in trial 5, and one cat jumped over only in trials 1–2.”

“Jumping over,” Pongrácz says, “can be considered as cats’ refusal to use the opening.”

I certainly applaud Pongrácz’s scientific dedication. π finds the “jumping over” particularly funny.

Species Comparisons. Pongrácz recounts, “Budgerigars and bumblebees were tested in such conditions where they had to fly through holes—where collisions during flight holds risk of injury. Therefore, in the case of these animals, the careful a-priori examination of the holes and the evasive posture while flying through were adaptive responses, most likely based on the representation of their own size and shape.”

“With regard to dogs,” Pongrácz says, “as they usually move at a fast pace, and their body is less flexible than it is in cats, their response of slowing down and looking for alternative solutions before arriving to a too small opening, can also be regarded as a biologically relevant strategy, aided by body size awareness.”

“However,” he observes, “such precautions would probably be superfluous for a cat, because of their specific features of locomotion, anatomy and space usage. Cats prefer environments with a complex structure (plenty of hiding places, vantage points, in other words: ‘obstacles,’ where they usually move slowly and with great agility.”

“More importantly,” he notes, “their anatomy supports flexibility and their free-floating, diminutive collarbones allow them to squeeze themselves through very narrow gaps.”

“If, of course, they want to,” π reminds us. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

A beagle, my current pet, would also consider gnawing the edges of the opening to enlarge it…

As both a cat, dog, and bee lover I found this incredibly interesting. I was only disappointed that no one thought to work in a “herding cats” reference anywhere.

l believe the researcher’s comment about “jumping over” covers that.—d

Perhaps it’s because many cats — like those shown in the photos — are mostly fur! One of our (late) felines looked like she weighed 15 pounds but on a scale was only nine pounds. Wet, she looked almost malnourished, except we knew better. As for herding cats, our (also sadly late) Queensland Heeler, without any sheep in the neighborhood, would herd the cat who followed directions but whined about it. The wonderful pooch had learned early on not to try to herd our other cat, another rescue.

First, any scientific study dealing with behavior of cats is instantly suspect as they seem to be genetically inclined to follow any instructions, react to stimuli or give repeatable results.

Second, note the relationship between the span of a cat’s whiskers and its size, and they use them as feelers for apertures and night vision. I recall scientific studies on this related to robotics and automation (once my field) and part of my Boy Scout lore.

One of the cruelest things you can do to a cat is trim their whiskers, as they’re crippled and confused until they grow back.

Finally – WordPress responds erratically for me when I use Firefox but seems better with MS Edge.

Assume you meant “….genetically DIS-inclined to follow any instructions….”

Yup … or words to that effect. Thank you.

(Was my comment edited by a childless cat lady???)