Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

KEEPING KEWL WITH AND WITHOUT VAPOR COMPRESSION PART 2

THIS ALL BEGAN WITH LEARNING ABOUT solid-state refrigerants as described in “Sizing Up Caloric Devices,” AAAS Science, August 2, 2024. Today in Part 2, three types of solid-state devices offer potential for a/c sans vapor compression.

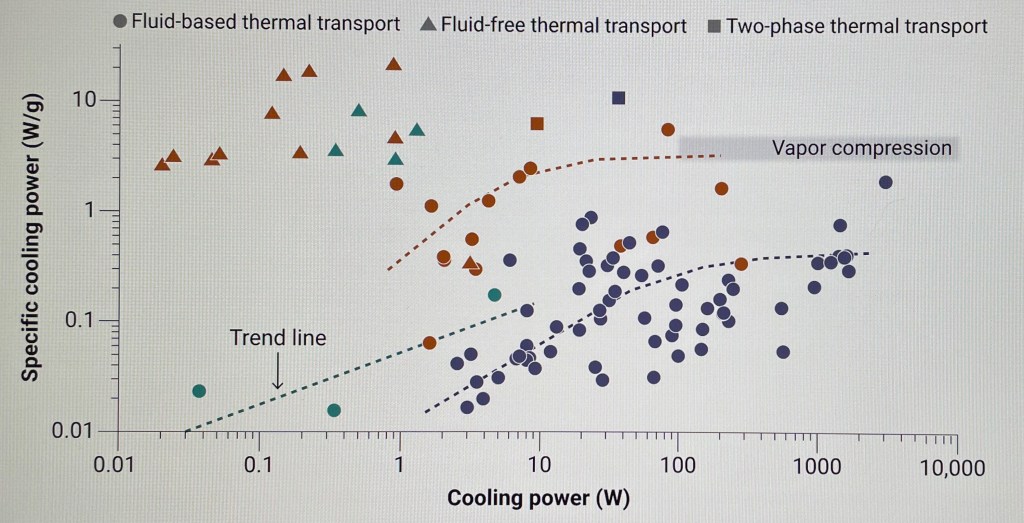

Image by A. Fisher/Science and M. Hersher/Science. Reproduced from Part 1 to save you flipping back and forth. It’s color-keyed to the device illos below.

Magnetocaloric Technology. “Cooling occurs,” researchers note, “when a changing magnetic field (H) changes the material’s spin…. Magnetocaloric cooling is the most dominant technology in terms of the sheer number, as these types of cooling devices have been around since the 1970s. Although not widely commercialized yet, kilowatt-capacity magnetocaloric refrigerators and air conditioners have been demonstrated.”

Magnetocaloric technology. This and following images from AAAS Science.

Electrocaloric Technology. Researchers describe, “An electric field (E) changes the electric dipole moment to drive cooling.” The researchers also note, “As such, the size scale of solid-to-solid contact cooling systems is intrinsically limited, as revealed by delivered cooling power ranging only from milliwatts to 3 W. Nonetheless, this high SCP makes fluid-free electrocaloric and elastocaloric cooling systems potentially suitable for efficient and compact thermal management in electronic devices, in computer chips, and for human skin.”

Electrocaloric technology.

Elastocaloric Technology. “Changing stress (σ),” researchers say, “affects the crystal structure to absorb heat.” Researchers observe, “Values of 20.9 and 19 W g–1 have been reported as the SCP of elastocaloric polymers and metal, respectively, and 7.9 W g–1 has been achieved with electrocaloric polymers. These numbers are larger than those of state-of-the-art commercial-grade thermoelectric modules.”

Elastocaloric technology.

Energy Star Ratings. Researchers note, “A key system-level metric is the overall system energy efficiency. This is the coefficient of performance (COP) at fixed input (Thigh) and output (Tlow) temperatures. The typical COP of vapor-compression air conditioners is 3.5 to 4 (with Thigh = 308 K and Tlow= 300 K according to the Air Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute 2020 standard), and this is reflected in the ubiquitous Energy Star ratings on appliances.”

They continue, “Given the high intrinsic efficiency of caloric processes at the materials level, there are reasons to be optimistic about the COP of caloric systems. A promising early data point is the report of a system COP of 1.9 at 12 K temperature span in a kilowatt-capacity magnetocaloric air-conditioning prototype. The latest breakthroughs in the boosted cooling power of electrocaloric and elastocaloric systems are perhaps signaling the coming of age of the calorics.”

You read it here first. At least I did.

A Personal Experience with Climate Change. I recently noticed my 2012 Honda Crosstour’s a/c was performing less than effectively.

Of course, the ambient temperature here in near-coastal balmy SoCal was 86º Fahrenheit at the time. Not particularly hot by global experiences these days (and, coincidentally, at one of my Celsius/Fahrenheit memory aids: 20-30 C = 68-86 F).

Crosstour Tales. Fact is, the Crosstour’s odometer just turned 30,000, and I’ve never had the a/c looked at in 12 years. So no complaints. I took the car to my favorite HB Automotive and A/C and, sure enough, one of the a/c pressure metrics that should have been 0.9 was at 0.4.

In my retired state of automotive engineering, I neglected to ask the unit. However, I vaguely recall the theory of vapor-compression a/c. (Mom always called me “book smart, head dumb.”) Wikipedia confirms my memory: “Vapor-compression uses a circulating liquid refrigerant as the medium which absorbs and removes heat from the space to be cooled and subsequently rejects that heat elsewhere.” PV=NRT is in there somewhere too.

Anyway, after restoring matters to 0.9 no leaks were identified, and two weeks later it seems even cooler with swapping the original cabin air filter for a fresh one.

Not bad for a 12-year-old car, I say. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

This revives a memory of a motor I learned about as a Cub Scout that used rubber bands arranged on an armature in such a way that when it was partially submerged in hot water, it would rotate.

Doc, sounds neat. Does it have a name?

“Rubber band heat engine”, oddly enough. There is a description in the Caltech Feynman lecture series in the thermodynamics section. However, it is a bit different than the way I remember it. Speaking of Feynman, I hope you’ve read, Surely you’re Joking!