Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

A BOND/MACMINN LE MANS COUPE IS HONORED AT AMELIA CONCOURS PART 1

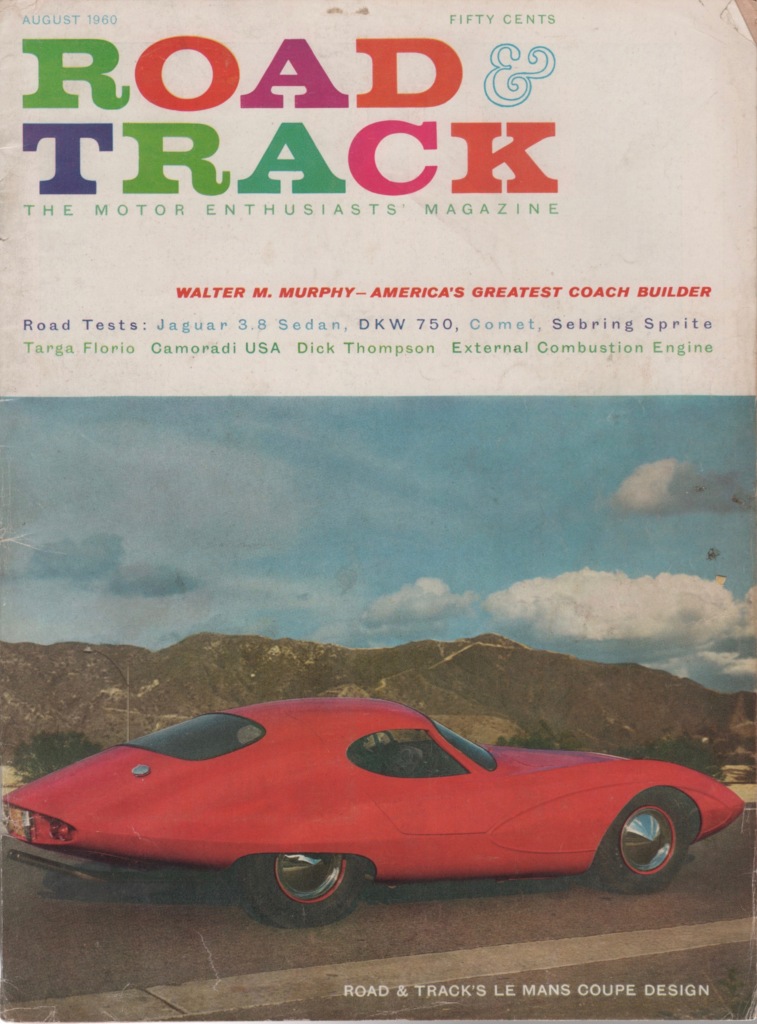

GARNERING THE CHIEF JUDGES AWARD at the 2024 Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance is a car identified in Classic & Sports Car’s May 2024 issue as the “wild 1958 Macminn Le Mans Coupe.”

Image from Classic & Sports Car, May 2024.

In fact, as these tidbits relate in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, the tale is rather more involved.

Briefly.… It begins in November 1957 with “An American Car for Le Mans,” Sports Car Design 39 conceived by R&T’s Publisher & Technical Editor John R. Bond. John continued the theme into Design 40 in R&T’s January 1958 issue, then refined it as Design 41 in February with contours by ArtCenter’s Strother “Mac” MacMinn, and the pair summarized the project in April’s Design 43.

What of Sports Car Design No. 42? This was a March 1958 analysis of Stan Mott’s Cyclops. Another tale for another day.

Road & Track’s Le Mans Coupe was the cover subject in R&T’s August 1960 with Strother MacMinn’s “Sports Car Design Realized.” Mac recounted, “A number of people wrote, expressing definite interest in attempting the project, and the series of articles actually did trigger three dedicated Southern California enthusiasts into action.”

Indeed, the tale continues past this as well.

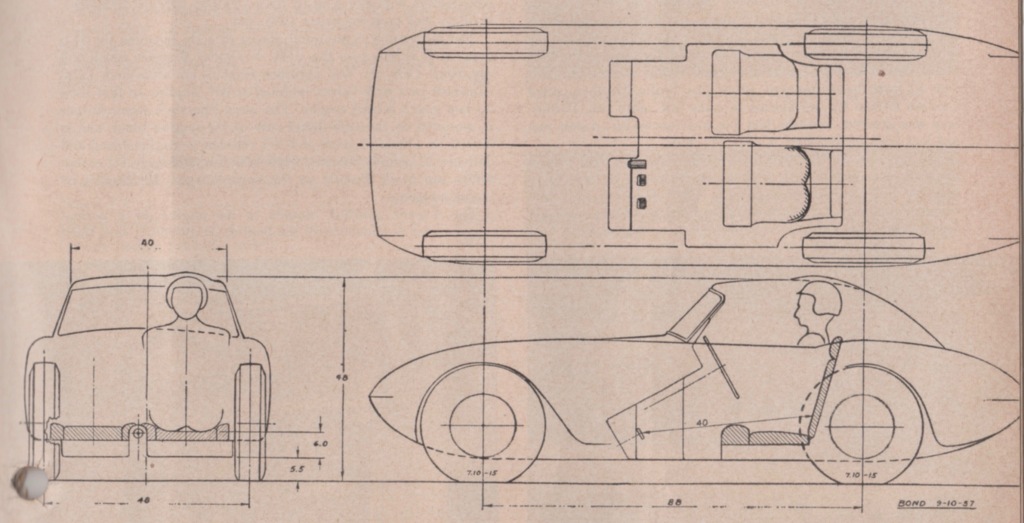

Design 39. In his preliminary proposal, John isolated three factors: horsepower, weight, and frontal area. He also noted, “we may as well state that a closed coupe is the optimal form for Le Mans. A fully roofed body offers the lowest wind resistance (and the highest top speed) which in turn means the fastest laps, provided the car is no heavier than an open car. A coupe can even ‘stand’ more frontal area than a roadster and still be a faster machine, other things being equal.”

John’s preliminary proposal gave small frontal area and met the era’s Le Mans specifications (considerably more complex following the venue’s 1955 disaster). Image from R&T November 1957.

Driver Comfort. “One of the commonest mistakes in sports car design,” John said, “is placing the pedals higher than the seat, or more correctly, the occupied seat. Sports car races are often long and always arduous, and no driver can do a good job for long with his feet higher than his derrière…. Many existing cars violate this arbitrary rule, but it is very doubtful if the 3 or 4 inches saved in overall height contribute as many added miles (in an endurance race) as are lost through driver fatigue and loss of efficiency.”

I wonder what John would think of current race car seating. Or, come to think of it, of race driver athleticism.

“We must also not overlook the fact that most drivers wear a helmet [i.e., not a soft one], and this requires extra headroom. The roof bulge shown is one solution, and the 1.5 inches that this idea saves in the height of the remainder of the roof cancels half of the extra seat height specified for comfort reasons.”

John’s logic was followed within a decade in the Ford GT-40’s roof bubble for the likes of Dan Gurney.

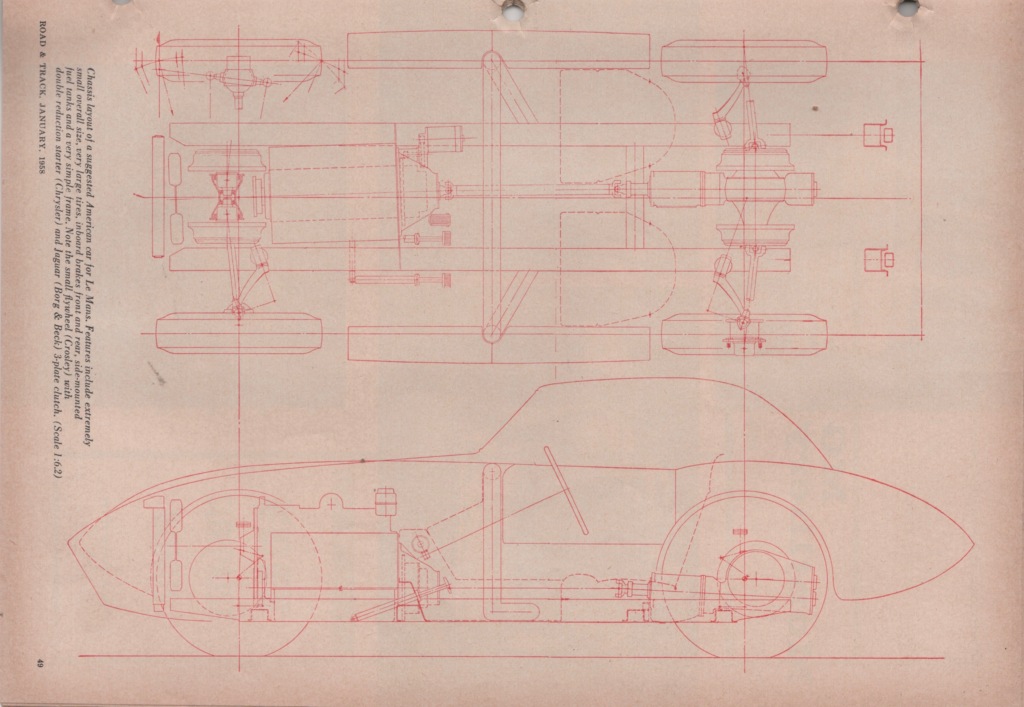

Design 40. John got downright serious about specific mechanicals: “The only choice of engine, if it must be American, is Corvette, because of its compact size and low weight. The new 3-liter limit means that the proposed machine could still run, but would not received championship points.” This was to get even worse with evolving regulations. By Design 43, John was thinking of “the experimental ‘La Salle II’ V-6 with single overhead cams and fuel injection.”

“Features,” John said, “include extremely small overall size, very large tires, inboard brakes front and rear, side-mounted fuel tanks and a simple frame.” Image from R&T, January 1958.

“We also,” John recounted, “have to face the problem of applying power to the rear tires. To hold speed in a 0.7g corner [remember, this was before aero downforce] requires power, the exact amount dependent on the speed and slip angle.”

“For neutral steering,” he continued, “generally considered the fastest way through a corner, we must compromise the front tires slightly. Otherwise, when power is applied, the rear tires will lose traction before the fronts, (increase their slip angle) and the car will oversteer.” John discussed changing camber angles, front and rear, and concluded, “With ample power available, the car will oversteer anyway; this is unavoidable.”

Inboard Brakes, Front and Rear. John conceded the added weight of mounting brakes inboard, but felt that the tradeoff of reduced unsprung weight was beneficial. He even specified mechanicals: Mercedes 300SL drums and front wheel spindles of “reworked Cord assemblies with a pair of opposed Timken bearings replacing the double-row ball wheel bearings.”

The Next Installment. “The third and last part of this article,” wrote John (not yet recognizing the need for still another installment), “will explain the difficulties we have had in getting a stylist and an aerodynamicist to agree on a suitable body design.”

Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll see how John handled this quandary. And maybe we’ll sense a need for a Part 3…. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

The bodywork seems to owe something to 57 varieties heir Rust Heinz’s ’36 Cord 810-based one-off 1938 Phantom Corsair, co-styled and built by Maurice Schwartz of Pasadena’s Bohman & Schwartz.

Just looked at that R&T last winter.JohnPS gave away over one thousand sports car magazines. Now have a couple thousand more to do something with.Keeping the ones from 40s thru 60s for a time.