Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

THE PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

THERE’S IRONY TO BE HAD in my having a Ph.D. in mathematics. This is at least in part because I spent the majority of my career working in automotive journalism, with only peripheral involvement in my math speciality of dynamical systems theory (what I call sorta differential equations without the dirty bits).

Indeed, there’s added irony in that Ph.D. stands for Doctorate of Philosophy. Yet I recall Philosophy 101 as one of the more baffling courses in my undergrad education. Sure, I learned about Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and those others of civilization’s great thinkers. I believe my skepticism arose with Bishop Berkeley’s denying the existence of the physical world yet nevertheless trusting that chair.

Maybe I was thinking too literally?

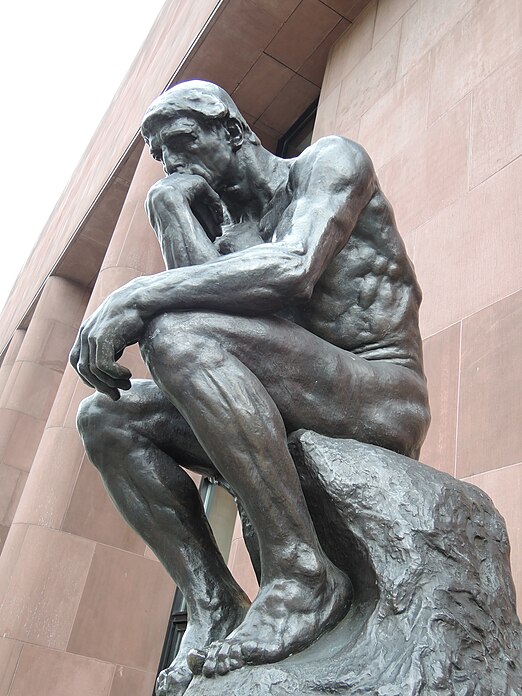

Le Penseur, by Auguste Rodin, 1904. Image by Kaisching from Wikipedia.

A Wikipedia Definition. According to Wikipedia, “Philosophy (φιλοσοφία, ‘love of wisdom,’ in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, value, mind, and language. It is a rational and critical inquiry that reflects on its own methods and assumptions.”

This last point about reflection leads directly to an editorial in Science magazine published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Thorp’s AAAS Editorial. H. Holden Thorp is Editor-in-Chief of the journals published by AAAS. His editorial “Teach Philosophy of Science,” April 12, 2024, addresses science, its public trust, and public understanding. Here are tidbits gleaned from the article.

H. Holden Thorp, Editor-in-Chief, AAAS journals; Rita Levi-Montalcini Distinguished University Professorship of Chemistry and Medicine at Washington University; Professor of Chemistry at George Washington University.

Public Trust. Thorp writes, “As Pew studies have shown, trust in scientists and medical scientists in the US is higher than for all other institutions surveyed except the military. There was a modest decline over the past 4 years, but a similar decrease was seen for other professions. In absolute terms, trust in scientists is at 73%, whereas trust in most other institutions is far lower, with business leaders at 35% and elected officials at 24%.”

I suspect modest declines are at least in part attributable to politicization in matters such as climate change, the Covid epidemic, and health care in general.

Science, a Work in Progress. “Most prominently,” Thorp says, “the study showed that 92% of respondents felt it important that scientists show they are ‘open to changing their minds based on new evidence,’ which is of course what they must do. Many scientists would be surprised to find that this idea needs to be reinforced.”

Thorp emphasizes an important point: “Science is, after all, a work in progress that changes as new findings cause revision and refinement of held interpretations. The history of science is a powerful narrative of this culture of self-correction, and it is the essence of science to attempt to make discoveries that change the way scientists think.”

Science, a Target. “But whenever science becomes important in the public eye,” Thorp notes, “as with climate change and the pandemic, the continuous revision can become a target for those who wish to undermine scientific knowledge.”

Or those who wish to politicize matters for their own gain.

“Scholastic Fallacy.” Thorp notes, “French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu coined the term ‘scholastic fallacy’ to describe the tendency of academics to assume that everyone thinks about problems in the way that scientists do. As Bourdieu points out, most people do not have the time and effort to spend thinking about these issues in the same way as those for whom this is a full-time job.”

As a consequence, Thorp says, “Academics often fail to recognize this and are mystified when the public doesn’t understand that interpretations are continually revised in light of new data, as has happened across history.”

Enhanced Philosophy of Science. “Resetting the public’s understanding of how science works will be a big job,” Thorp says, “but a good place to start is with students who get science degrees. Unfortunately, most programs are full of didactic classes about scientific principles, with few if any requirements on the history and philosophy of science.”

Thorp continues, “Because many undergraduate science majors pursue careers outside of science, including medicine, a shift in curricula would ultimately produce a public that is more literate in the way that science works.”

And, of course, a more discerning public is better able to make important decisions to the benefit of us all. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

Be interesting to know who, precisely, these 92% of respondents are; their backgrounds, reading, who imagine scientists require their assurance that they are “open to changing their minds based on new evidence,” when we live in a nation producing but a quarter per capita the scientists, doctors, engineers as China, India, Pakistan, and must import same. And when we’ve a presidential candidate wanting to drop nuclear bombs on hurricanes, who told Covid sufferers to imbibe bleach, thinks humans invented asbestos, says climate change a hoax, while selling designer Bibles.

Philosophy and religion are just that. Science brings us usable knowledge, expands engineering and medicine.

Who was more important to human development, Immanuel Kant or Isaac Newton?

Parse philosophy, peruse religious tales and edicts if you wish. But don’t kid yourself their relative import.