Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

CATCHIN’ ZZZS WITH THE WADDLE

ANIMALS OF ALL SORTS, HUMANS INCLUDED, engage in microsleep, seconds-long interruptions of wakefulness. Why they/we do it is not completely clear, as the short duration may have little benefit in restorative functions of the brain. However, as reported in Science, December 1, 2023, researchers have studied microsleep in chinstrap penguins. Science editor Sacha Vignieri notes, “The penguins nodded off more than 10,000 times a day, for only around 4 seconds at a time, but still managed to accumulate close to 11 hours of sleep. Their breeding success suggests that this strategy allows them to get the sleep they need.”

Here are tidbits gleaned from “Nesting Chinstrap Penguins Accrue Large Quantities of Sleep Through Seconds-long Microsleeps,” by P.-A. Libourel et al, Science, November 30, 2023, together with my usual Internet sleuthing.

Well-named. As noted by Wikipedia, the chinstrap name comes from a narrow black band under the penguin’s head: “Other common names include ringed penguin, bearded penguin, and stonecracker penguin, due to its loud, harsh call.”

Its Latin name Pygoscelis antarcticus derives from “rump-legged” suggested by its brush tail; antarcticus identifies its range (with an orthographic correction in Latin grammar from an earlier antarctica).

Chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarcticus). Image from US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration from Wikipedia.

Chinstrap Napping. Like other creatures, chinstrap penguins can sleep selectively. (Dolphins, for example, sleep with only half their brain at a time.) The researchers identified two kinds of chinstrap napping: Unihemisphere Short Wave Sleeping (USWS) and Bihemisphere Short Wave Sleeping (BSWS).

Napping Methodology. “Using data loggers,” the researchers write, “we measured sleep-related EEG activity from both cerebral hemispheres, the electromyogram (EMG) from the neck muscles, body movements and posture with accelerometry, location with GPS, and diving with a pressure sensor. BSWS and USWS were automatically scored using hierarchical clustering and individual thresholding on the EEG.”

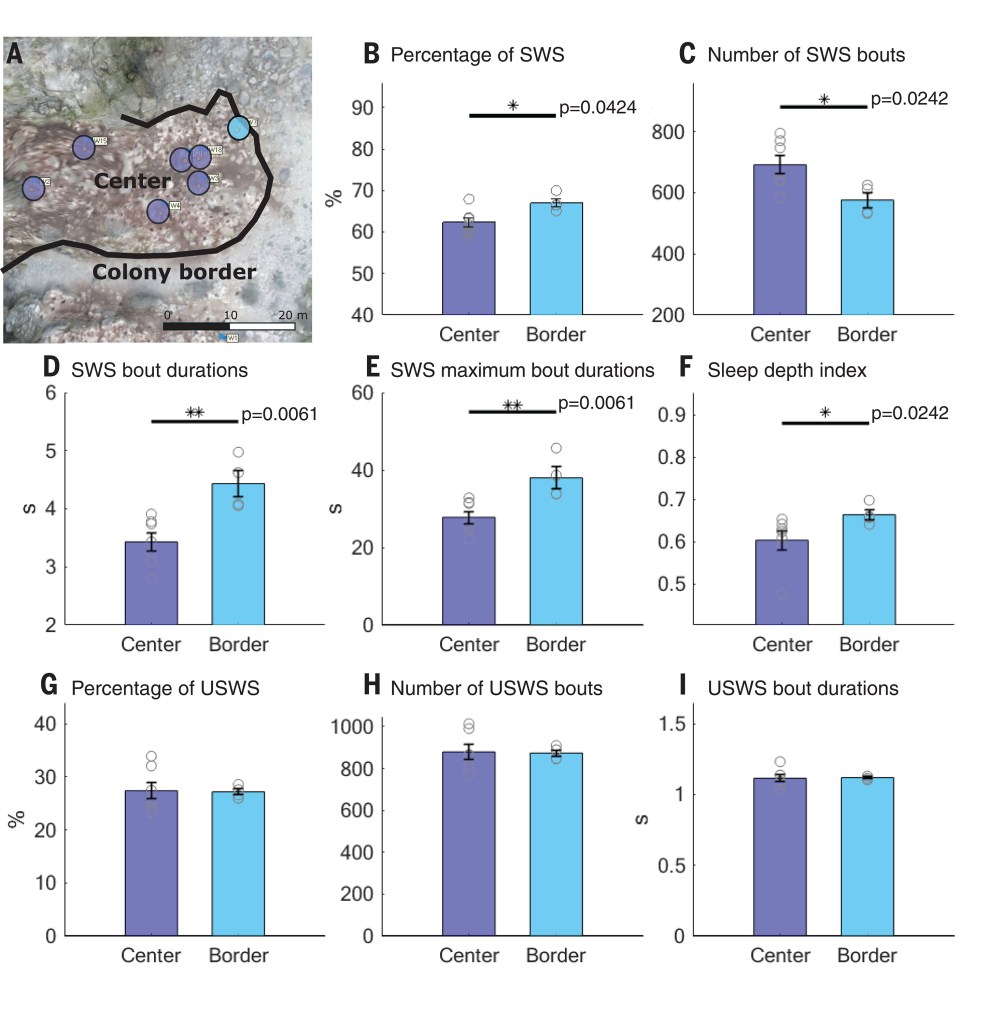

This and other images from Science, December 1, 2023.

Hazards of Chinstrap Parenting. The brown skua is a large seabird which curiously enough Wikipedia writes has been noted “for sometimes bonding with humans who live for extended period in Antarctica, such as the Eastern Orthodox at Trinity Church, and engaging in playful or apparently mischievous behavior with them.” The corvids are also known to behave this way with humans.

Among other skua mischief is preying upon the eggs of chinstrap penguins. Nor are penguin colonies all that benevolent locales. The researchers observe, “As one penguin parent must therefore guard the eggs or small chicks continuously while its partner is away on foraging trips lasting several days, they face the challenge of needing to sleep while protecting their offspring. In addition, they also have to effectively defend their nest site from intruding penguins.”

Which is Safer: Deep Within the Waddle or at its Border? “Given the threat from outside and the hustle and bustle within the colony,” the researchers say, “it is unclear whether nesting in the center of a colony leads to better sleep quantity and quality.”

The results show interesting contrasts: “Nests were classified as either on the border or in the center (>2 m away from the border) of the colony (Fig. 3A). Birds nesting at the border obtained more SWS (Fig. 3B), through fewer (Fig. 3C) but longer bouts of SWS (Fig. 3D) than those in the center of the colony.”

Researchers continue, “The maximum duration of SWS was also longer in birds incubating at the colony border (Fig. 3E), and birds at the border slept more deeply than those in the center (Fig. 3F). Also, none of the variables for USWS (percent of time, number of bouts, and bout duration; Fig. 3, G to I) varied significantly as a function of nest position. Consequently, contrary to predictions based on mallards, birds nesting at the colony border slept better (more, deeper, and less fragmented sleep) than those nesting in the center, and they did not engage in more USWS.”

Perhaps as expected (recall the stonecracker penguins’ “loud, harsh call”), hanging out within the waddle is not the more restful. I know human assemblages for which this is the case. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023