Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

G.P. MERCEDES OF MORE THAN A CENTURY AGO PART 2

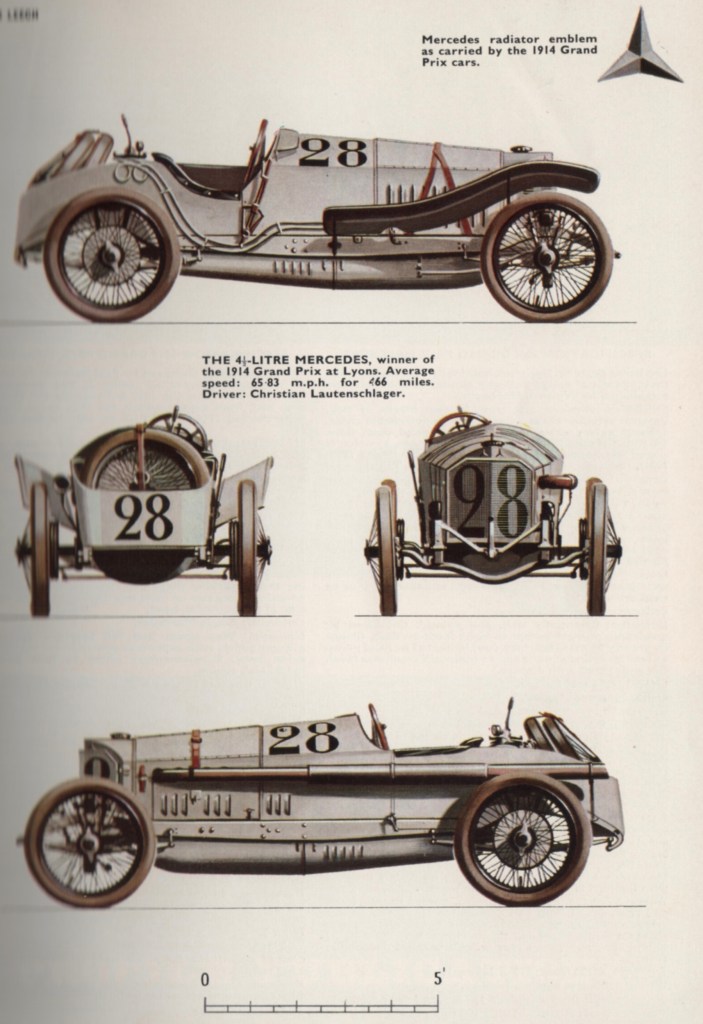

YESTERDAY, ANTHONY BIRD OFFERED ANALYSIS of the 1908 G.P. Mercedes, a 12.8-liter behemoth winning the Grand Prix at Dieppe much to the consternation of the French (who, in a sense, pouted for two years without international Grands Prix). Today, both Bird and Laurence Pomeroy examine the 1914 G.P. Mercedes, a car that was conservative in some ways (no front brakes, for example), yet advanced in others and exploiting the 4 1/2-liter limit in force for the Grand Prix at Lyon. Here are tidbits gleaned from Bird’s article in Classic Car Profiles 1-24 as well as Pomeroy’s having the 1914 G.P. Mercedes as one of the 17 cars analyzed in The Grand Prix Car Volume One.

Illustration by L.C. Cresswell from The Grand Prix Car. Note the 1914 car’s knock-off wheels and eschewing of chain drive.

Sacred Cows Destroyed. Bird wrote, “A look at some of the technical details destroys three of the sacred cows of motoring history: Firstly—that aero engine practice did not influence car engine design until after the war. Both the 1913 and 1914 Mercedes racing engines had much in common with the firm’s well-known aero engines.”

The other two sacred cows involved final drive design and engine speed. In particular, Mercedes’ “inferior” torque-tube layout would lead to rear wheel steering. Bird observes, “Despite the pundits who assure us this arrangement promotes oversteer, the cars steered beautifully.”

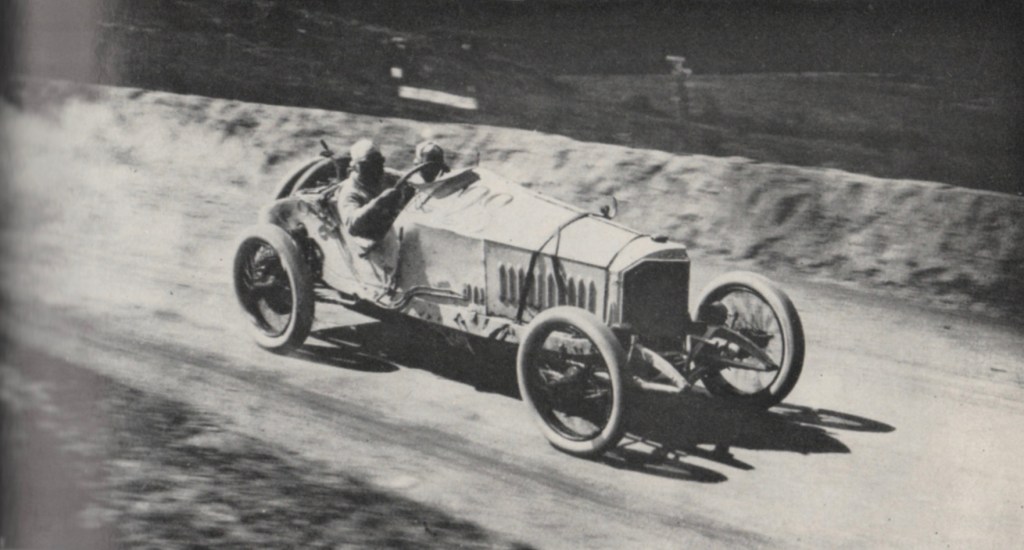

Lautenschager takes a fast corner on his last lap. This and other images from Classic Car Profiles.

Huge Engines = Large Flywheels. “The photographs,” Bird noted, “say all that needs to be said of the way racing cars had changed externally in six years. It must be remembered, however, that the high build and sit-up-and-beg driving positions of 1908 had not been retained purely by conservative adherence to touring car fashion. The very large engines had very large flywheels, and to give 6 or 7 inches clearance beneath a flywheel nearly two feet in diameter dictated a high chassis and floor level.”

“On the 1914 Mercedes this dimension was reduced by some 10 or 12 inches, and the very narrow body (37 in. at the widest point) and coupe vent radiator helped reduce drag.”

Aero-engine Influence, Up-to-Date. “The cutaway drawing,” Bird observed, “shows the 1914 4483-cc Mercedes G.P. engine: the apparently old fashioned exposed valve springs and stems were retained to aid cooling and make for easy adjustment, but the crankshaft dimensions and combustion chamber and valve ports would have passed as up to date until quite recently.”

In particular, the engine had four valves per cylinder (an innovation introduced by Peugeot in 1912).

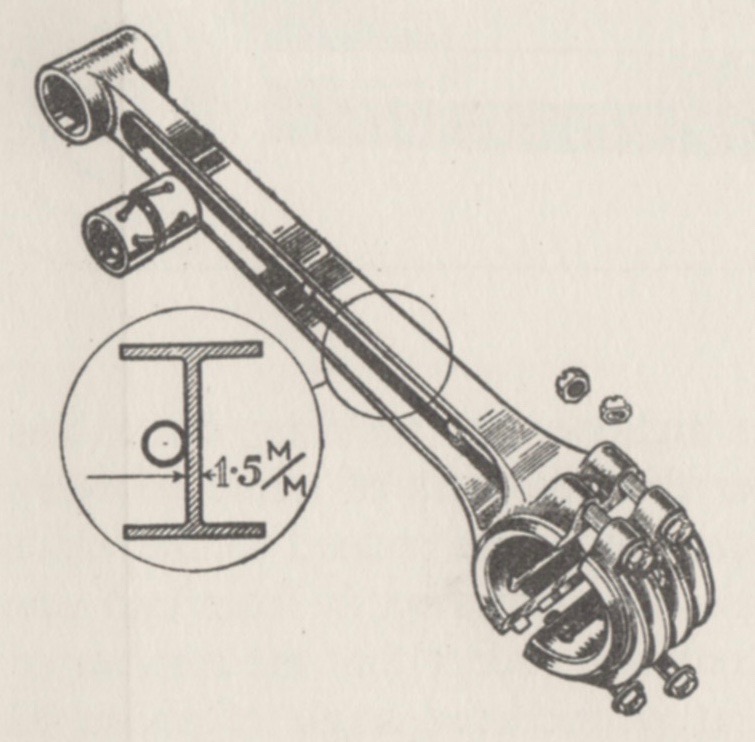

Adieu, Drip-and-Splash. Bird said, “the drawing also shows the plunger-pump system of pressure lubrication (the 1908 engines had still relied upon drip-feed-and splash basically.”

In The Grand Prix Car, Pomeroy offered an extended paragraph describing its intricacies and L.C. Cresswell included details of the triple pump lubrication unit (with the added comment “vide text.”

Mercedes triple-pump pressurized lubrication. This image and the following from The Grand Prix Car.

Both Bird and Pomeroy noted that this mechanical system was supplemented by another pump operated by the mechanic’s foot.

Machinist’s Art. Pomeroy continued with a fulsome description of the engine’s connecting rods: “The big ends,” he wrote, “were also white metal cast into detachable bronze shells, the rods themselves being particularly fine examples of the machinist’s art with the web only 1.5 mm. thick.” Once again, Cresswell confirmed matters.

Replacing Chains. Pomeroy described, “The detail of the rear axle is yet a further example of the immense thoroughness with which these cars were prepared. The crown-wheel was in one with the half-shaft, the latter being hollowed to save weight. Sufficient half-shaft-cum-crown-wheels and pinions were constructed to give a choice of six alternative ratios between 2.2 and 2.7:1.”

“The choice of gear ratios,” Pomeroy continued, “was indeed a severe headache for the designer. The 23.3-mile Lyons circuit was popularly supposed to have 100 corners: it certainly embraced a difference of 700 ft. between the lowest and highest point, and one leg consisted of an eleven-mile switchback straight.”

Three of the five Mercedes entries finished 1, 2, 3. Illustration by James Leech from Classic Cars in Profile 1-24.

War to Come. Bird recounted, “Four weeks later the pistol shot which started the war was fired. A macabre twist to the tale is provided by the fact that the chauffeur at Sarajevo who was wounded in the attempt to drive the murdered Archduke out of range was Otto Merz, a Mercedes apprentice, one time riding mechanic to Poege and himself a famous racing driver in the ’twenties.’” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023

The rapid sophistication witnessed in the above over the nascent motorized buckboards of only eights years prior is staggering.