Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

U.S. AIRMAIL TIDBITS PART 1

THOSE OF A CERTAIN AGE will recall writing “AIR MAIL” on envelopes (and adding extra postage) for this special service. Imagine that; how quaint. Posting “letters” to be delivered by humans, not email. And what humans they were: Earle Ovington performed the first authorized U.S. Mail flight in 1911 in his Blériot, the same sort of craft in which Louis Blériot crossed the English Channel in 1909. Katherine Stinson (her surname, a familiar one in aviation) was the first woman to deliver U.S. Mail by air in 1913. And in 1926, a fellow named Charles Lindbergh was chief pilot of a company specifically contracted to fly the mail.

Here, in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, U.S. airmail tidbits are gleaned from the about.usps.com website, from Chronicle of Aviation, and from my usual Internet sleuthing.

Long Island’s Garden City Estates to Mineola. “In 1911,” the U.S.P.S. website recounts, “the U.S. Postal Service authorized the first mail flights at an aviation meet on Long Island, New York…. Aviator Earle Ovington had the distinction of piloting the first history-making flight, on September 23.”

Seven pilots, the website describes, “made daily flights from Garden City Estates to Mineola, New York, dropping mailbags from the plane to the ground where they were picked up by Mineola’s Postmaster, William McCarthy.”

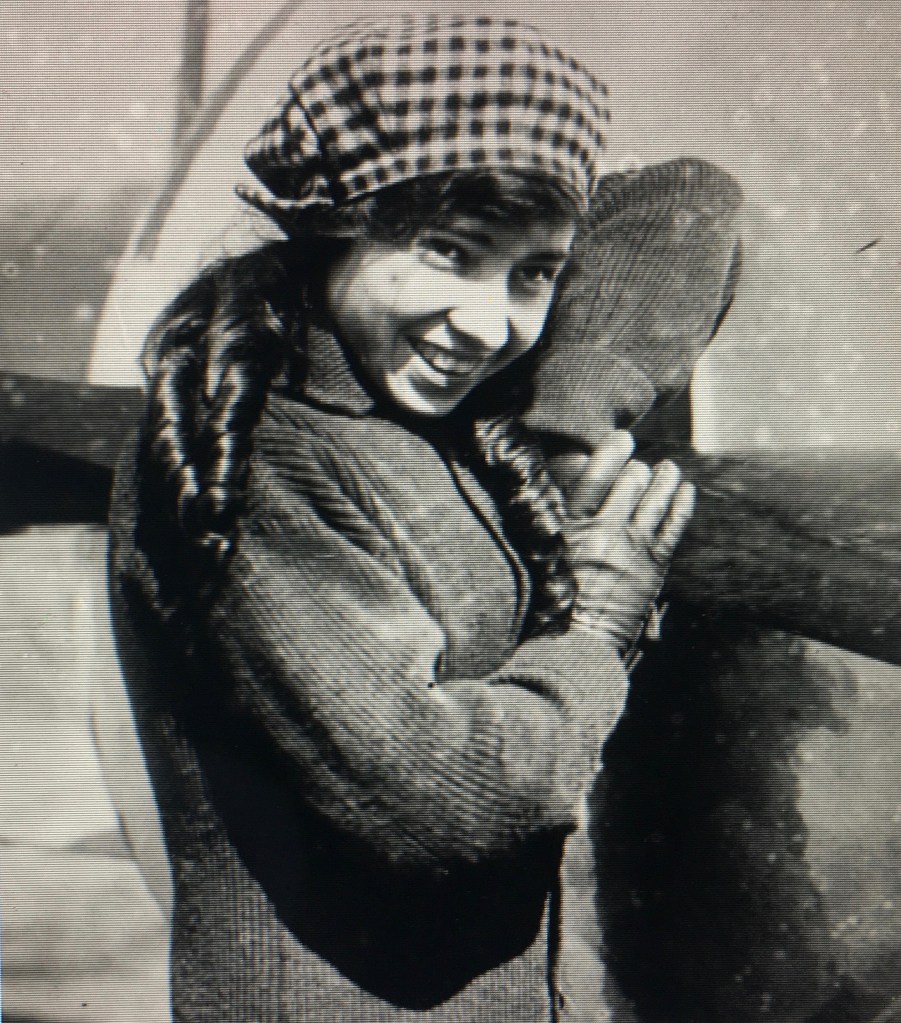

Airmail Delivery by a “Flying Schoolgirl.” “In 1913,” the Postal Service writes, “22-year-old Katherine Stinson became the first woman to fly the U.S. Mail when she dropped mailbags from her plane at the Montana State Fair.”

Chronicle of Flight reported, with a dateline Montana, September 27, 1913: “Over the past four days, she has carried 1333 letters and postcards at the Montana State Fair in a publicity stunt to promote a Montana airmail service. Known as ‘The Flying Schoolgirl,’ she came to aviation by a strange route. Her first love was music, and she took up flying to pay for her piano lessons. But she was so struck by life in the air that she abandoned all to win her pilot’s license. Her younger sister Marjorie has been bitten by the bug and is following her footsteps.”

The Postal Service continues, “Stinson captivated audiences worldwide with her fearless feats of aerial derring-do. In 1918, she became the first woman to fly both an experimental mail route from Chicago to New York and the regular route from New York to Washington, D.C.”

And, in 1920, Katherine’s brother Eddie established Stinson Aircraft Company in Dayton, Ohio. The firm was later merged with Cord of automobile fame, then AVCO, later Consolidated Vultee, and, in 1948, was sold to Piper Aircraft.

Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll learn about an airmail pilot named Lindbergh and how another may have earned the equivalent of $164,264 in today’s dollar. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023

The Boeing B-1 was their first commercial plane flying international mail between Victoria BC and Seattle. It is on display at a museum in Seattle. Here is a picture of it:

Sorry . It seems that the link was removed. Try adding the dot yourself.

mohai[dot]org/collections-and-research/#see-the-collection

Hi, Bill,

At one point I considered doing a GMax Boeing B-1. I didn’t follow through, at least in part because of its design similarities with the Benoist flying boat flown by Tony Jannus on the 1913 Tampa/St Petersburg Airline. Both neat craft with neat histories.

Interesting about Stinson. Good to see the distaff get praise.

For more early air mail, anything by Antoine de Saint Exupery. His Wind, Sand and Stars (1940) a jewel.

Antoine de Saint Exupery was an airmail pilot, and while Wind, Sand and Stars is poetic, his Night Flight dramatically delves with the danger and drama of flying the mail.

Dennis – Are you aware that that Benoist used in the Tampa/St. Pete air service is considered the first scheduled airline?

I like the variety of AirMail schemes tried and employed. In the 30s, a string of gliders, linked nose to tail behind one tow plane, with them dropping off at intermediate points was tried by the Lustig Skytrain test. A similar method was considered for aerial freight, based on the efficiency of multiple craft and one tow plane.

For mountain towns, too small for an airport, the All American Air Service would fly over a postal area, drop a padded pouch, and swoop down, hooking up another mail pouch.

This method was used in WWII to pick up troop gliders in Europe and Burma, and spies or bailed out airmen behind enemy lines.

All American became All American Airlines, then Allegheny Airlines, then USAir.

Finally, in the 40s a small glider pickup method was used to deliver hundreds of pounds of fresh lobsters from Maine to a small landing beach on the South tip of Manhattan. They’d be rushed to local restaurants, and the glider using the All American technique to return for more crustaceans.

Sure. There’s an item here, some time back, on Tony Jannus and saving the time driving around the bay.