Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

IS THERE AN ALCHEMIST IN THE HOUSE?

ALCHEMY WAS MORE than changing base metals into gold. Malcolm Gaskill reviews Jennifer M. Rambling’s The Experimental Fire: Inventing English Alchemy, 1300–1700 in the London Review of Books, July 15, 2021. In his review titled “Philosophical Vinegar, Marvellous Salt,” Gaskill observes “… alchemy was not an academic field in its own right. It was a slanted approach to intellectual inquiry, the pursuit of knowledge tout court, with intelligent links to medicine, metallurgy, oenology, physics, chemistry, biology, theology, moral philosophy, iconography and creative writing.”

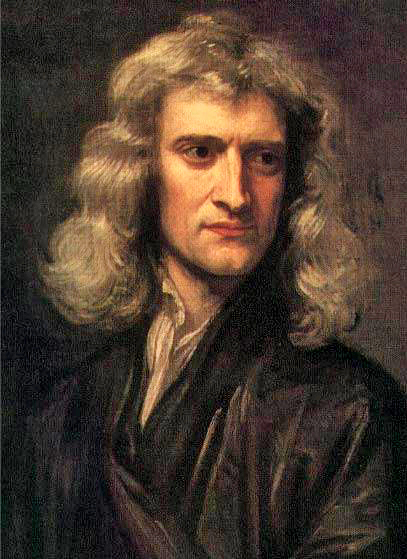

True, its practitioners ranged from the charlatan in Chaucer’s “Canon Yeoman’s Tale” to no less than Sir Isaac Newton. And Gaskill’s review of Rampling’s book is replete with tidbits.

Malcolm Gaskill is emeritus professor of early modern history at Britain’s University of East Anglia. Jennifer M. Rampling is associate professor of history at Princeton University.

Alchemic Origins. Gaskill writes, “Much of the Western alchemical tradition grew out of knowledge spreading from Hellenistic Egypt and the Holy Land, and from Jewish and Islamic scholars, such as the Arab physician Avicenna, who discoursed on ‘philosophical’ elements (mercury, sulphur and salt) as well as conventional ‘material’ elements.”

“By the 13th century,” Gaskill continues, “philosophical elements had become the cornerstone of Paracelsian medicine. Many English alchemists were monks and friars, who took trips abroad to track down parchments relating to geometry, magic, theology, medicine and alchemy. The most popular text was the Secretum secretorum, supposedly Aristotle’s teachings as passed directly to Alexander the Great, translated from Arabic into Latin.”

Alchemists’ Bad Rap. “One reason that the reputations of alchemists like Ripley [a 15th-century practitioner] survived, even into the late 17th century, is that the procedures they recorded were so cryptic it was hard to confidently determine that they were wrong.”

This reminds me of some of today’s political practitioners.

On the other hand, Gaskill observes, “It only looks like a pseudo-science if we starkly juxtapose it with enlightened modernity. Alchemy had no substance, in the sense that no one ever managed to make precious metals from base ones—but then neither did theology or astronomy (read: astrology), both also thoroughly speculative disciplines.”

The Alchemistic Monetary Con. The transformation of base metals into gold had evident attraction. Gaskill writes, “Though debasing the currency with artificial coin was outlawed, it was fine for cash-strapped monarchs to do it, if they found men of experience to assist them.”

For example, Gaskill notes, “Early in the 15th century, multiplication of metal was forbidden by Henry IV, not because the act was intrinsically sinful, but because—as with minting coin—the crown had to have a monopoly.”

Henry VIII and Alchemy. Gaskill observes, “Henry VIII set alchemy back by dissolving the monasteries, which disrupted work and caused manuscripts to be lost, both in religious houses and the college libraries of Oxford and Cambridge. Furthermore, given the windfall provided by the dissolution, the king had no need to make gold: in this sense Thomas Cromwell was his alchemist.”

Isaac Newton’s Multiple Role. From 1696 until his death in 1727, Sir Isaac Newton served as Warden and Master of the Mint. It was a time of currency reform, counterfeiters, and clippers.

Clippers shaved circumferences of coins, then remelted and resold the precious metal. Thus, the ridged circumference of today’s coins, dimes and above. Apparently ridging is not worth the trouble for nickels or pennies.

Keynes’s Newton. Twentieth-century economist John Maynard Keynes was a collector of Newton’s writings. Gaskill notes, “On his death in 1946, Keynes bequeathed what is now a priceless collection … to his Cambridge college, King’s, complete with a memorable tagline of his own devising. These esoteric writings demonstrated that Newton was not after all ‘the first of the Age of Reason, he was the last of the magicians.’ ”

Might that apple falling from the tree had been a Golden Delicious? ds

© Dennis SImanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2021