Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

BROTHER, CAN YOU SPARE A CURLICUE? I’M A LITTLE SHORTHANDED HERE

AT A recent book exchange, I swapped six bags of my literary has-beens for one bag of treasures. (The affair was enlivened when I mistakenly put a copy of the Marquis de Sade’s Justine on a table intended for kids books.)

A particularly bright older book caught my eye, a 1950 Anniversary Edition of Gregg Shorthand Dictionary.

Gregg Shorthand Dictionary: Anniversary Edition, by John Robert Gregg, S.C.D., Gregg Publishing Company, 1950.

John Robert Gregg invented this form of stenography (the word, from the Greek, stenos narrow and graphia writing) in 1888. There have been other methods of shorthand, though Gregg’s is said to have followed Major Beniowski’s 1845 The Anti-Absurd or Phrenotypic English Pronouncing and Orthographical Dictionary. (Don’t you love the title?)

Gregg’s Anniversary system dates from 1929. This simplified version was originally intended for 1928 publication, but what with one thing and another…. (I’m beginning to like John Robert Gregg more and more.) There is a Centennial system, updated in 1988, about which I have no bibliophilic interest because it’s not an old book. (I have tee shirts that old.)

All of the Gregg shorthands are based on phonics, the sounds of words, not their English spelling. (A good thing, what with “they’re,” “their” and “there,” y’know?) There are 35 basic strokes combined to form words. Also, to speed things up (in application, not learning), Gregg shorthanders use them as “brief forms” for common words: “You” or “your” end up simply as the “u” sound. “Go” or “good” simply use the “g.” Thus, the phrase “U go good, grrl!” looks like a little skip, two bounds and a gentle landing.

U Go Good, Grrl! These and the following from Gregg Shorthand Dictionary Anniversary Edition, shorthand written by Winifred Kenna Richmond.

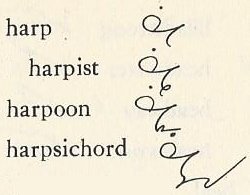

The Gregg Shorthand Dictionary is fun to peruse because of its logic and all-inclusiveness. For instance, the “harp” shape evolves into “harpist,” of course, but also “harpoon” and “harpsichord.”

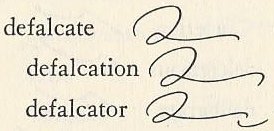

Nor are obscure words avoided: “Defalcate” looks like an artful numeral 2. Its tail gets increasingly fancy to indicate “defalcation” and “defalcator.”

Pause here to look up “defalcate.” Google says, “Embezzle (funds with which one had been entrusted).” This sounds redundant to me. Are there other embezzlers lacking initial trust? If so, didn’t the embezzlee get just what he deserved?

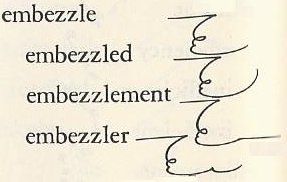

Embezzle/embezzled/embezzlement/embuzzler look rather like elaborate 7s with increasingly long tails. Embezzlee is not noted.

My copy of the book also contained a separate scrap of paper containing a shopping list: bread, matches, lettuce, olives, radishes, celery, potatoes. I note pointedly this list was written en clair, not in shorthand.

To the best of my knowledge, only two people of my acquaintance knew this art. One was Loraine Keaton, copy editor at R&T, rest her sweet soul, who also knew how to tap-dance. The other was secretary to a colleague at the Society of Automotive Engineers. He used to type first drafts of letters, then give them to her for final versions. She would say, “I know shorthand, so please dictate them because I can’t read your typing.”

Nor, come to think of it, can I read my own shorthand. Too many look like abundantly tailed numerals. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2015

My Mom taught Gregg (not Pittman) in Roxana Illinois High around 1941. Tried to impart it to me when I was twelve. Her book looked just like yours. You need to chase down an antique court steno typewriter that made these characters and had to then be transcribed back for court records.