Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

A FORMULA OF BEAUTY

THIS CONVERSATION took place years ago, 1986, to be exact:

“We all recognize that a 1964 Ferrari 250 GT Lusso is better looking than a 1958 Buick,” I said, “but why is this so obvious to everyone from Giorgio Giugiaro to an Eskimo?”

“What’s the big deal?” responded Managing Editor Dottie, “just run two photos.”

I was persistent then; and I remain so 26 years later: Is there a metric, a mathematically analyzable description, of automotive beauty? Or of aesthetics in general?

This traces to a monograph on the subject, “Mathematics of Aesthetics,” by George David Birkhoff. It’s in The World of Mathematics, a classic four-volume collection of such essays.

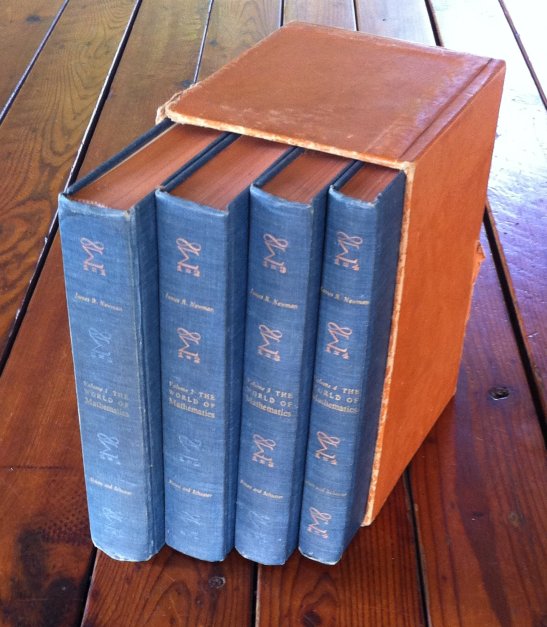

The World of Mathematics, A small library of the literature of mathematics from A’h-mosé the Scribe to Albert Einstein, presented with commentaries and notes, by James R. Newman, Simon and Schuster, 1956. Both Amazon.com and ABEBooks.com list it.

Birkhoff’s analysis begins by looking at the object and sensing its harmony, its discord, its aesthetic effect on us. This takes some effort, depending largely on the thing’s complexity: A Fellini film wears us out, a Disney flick doesn’t. A hexagon generates more intellectual tension than a cirle.

With a car, each element requires a little episode of viewer concentration. The front fender sweep, A. The wheel design, B. The window shape, C. Also, many elements repeat: two front fenders, four wheels, etc. Let’s use a, b, and c for these corresponding repeats.

Then we can define a car’s (or any object’s) total complexity by

COMP = aA + bB + cC + ….

This is what we put into the aesthetic experience. Next, what do we get out of it?

We get sensations, prompted by associated ideas and feelings. Symmetry, for instance, is a visual pleasure. Repetition of a character line is another, as are elements in balance as well as combinations of color. Underlying these and similar aesthetic pleasures is what’s known as “formal” order.

There’s another kind of aesthetic order that’s “connotative.” We appreciate the Lusso’s exhaust note not because of its particular tonal structure, but rather because we associate it with the car’s power, mechanism and mystique.

We identify the elements of order in a manner akin to our formulation of COMP. S might be the Lusso’s left/right symmetry; T, its echoing of a particular arc; U, the connotative order of its exhaust. And, once again, some of these repeat, s, t or u times.

Then ORD = sS + tT + uU +…. is the totality of order exhibited by the object we’re considering.

Finally, we define the object’s aesthetic merit, AEM = ORD/COMP.

In a sense, it’s measuring the density of order. If two objects are equally complex, the more orderly is aesthetically more pleasing. If two offer identical order, the less complex is better looking.

An 18-century Dutch philosopher, Frans Hemsterhuis, wrote “The Beautiful is that which gives us the greatest number of ideas in the shortest space of time.”

Or, we could just run two photos. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2012

Dennis,

If beauty could be reduced to a mathematical formula, it would be neither in the eye of the beholder nor would we need people to try to explain why a Lusso might be more beautiful than a Buick when both actually are beautiful.

Hi, Larry,

A good point.

I’m reminded of Nuccio Bertone’s comment: “We must never forget that Mr. Toad’s idea of beauty is Mrs. Toad.” – d

Is it too much a generalization to suggest a negative correlation for chrome? Consider one of my favorites from the era . . . the ’57 Olds, after allowing for the outsized bumper/grill.

Dennis:

Suz said your blog was fun and she was right. One of the troubles with math and beauty is that aesthetic beauty is always subtle. Any formula that scores objects numerically would put similar things together. The photo of the GT Lusso reminds me of the Saab Sonnet which was unquestionably an ugly car, even though it looks more similar to the Lusso than the 58 Buick. While mathematics can’t describe beauty, it can achieve beauty when expresses universal things simply. Things that are subtle, however, are rarely universal.

– Bill

A Formula that is food for thought. A class mate in my junior high school math class was unable to remember the Pythagorean theorem during a test. His answer: A squared + B squared = cake + cookies.

An Edsall making comments about automotive beauty? Larry, get real.