Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

LIGHTING OPERA

GIVEN THAT IT WAS A TEENAGE AMBITION OF MINE, I read with interest Anthony Freud’s “Illuminating the Stage,” Opera With Opera News, February 2026. In this article, he speaks with three of “the world’s most experienced and distinguished lighting designers, Paule Constable, Fabrice Kebour, and Duane Schuler, who talk “about their elusive craft which focuses storytelling and enhances emotion.”

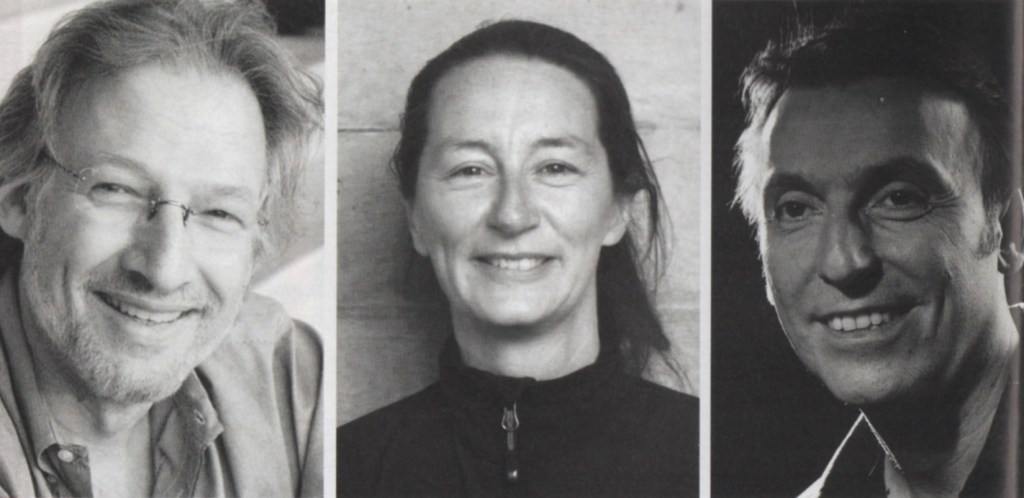

From left to right, lighting designers Duane Schuler, Paule Constable, and Fabrice Kebour. This and the following images from Opera With Opera News.

The Goal. Freud observes, “A skilful lighting designer will punctuate what we are hearing and seeing, intensifying the emotional punch of key musical moments, and focusing our attention on important elements of the production. But to be effective, lighting should work on a subconscious level: We must feel the impact without being conscious that light played a role in intensifying our feelings.”

The Mood, Then the People. Duane Schuler says, “Visibility is not the point, as it can easily lead to boring results. You have to create a mood onstage, a world that is believable and that reinforces what the opera is about. Then you add the visibility…. Light the world onstage before the people.”

Duane Schuler’s lighting for Laurent Pelly’s production of Cendrillion at Santa Fe Opera in 2006, wth Joyce DiDonato in the title role.

“A lighting designer’s goal,” Schuler says, “is to serve the piece, not to say ‘look at me.’ My job is well done when for 90 per cent of the time, people don’t notice what I’m doing.”

A Distillation Process. “I always try to simplify things,” says Paule Constable. “It’s very easy to end up with too much lighting a space, so that the light becomes valueless, just more stuff. When we are producing a piece, we are distilling it, trying to capture its essence for the audience. I am trying to do the same with light.”

Les Contes d’Hoffmann at the 2023 Salzburg Festival, directed by Mariame Clément and lit by Paule Constable, with Benjamin Bernheim (Hoffman) and Kate Lindsey (Nickausse).

Constable observes, “Seeing someone half lit can be much more intruguing for an audience than seeing someone fully lit.”

A Feeling of Darkness, Not True Darkness. Fabrice Kebour says, “That feeling comes when you have trouble seeing every detail. Every situation is different, but basically you use directions of light that shape the forms but don’t show them.”

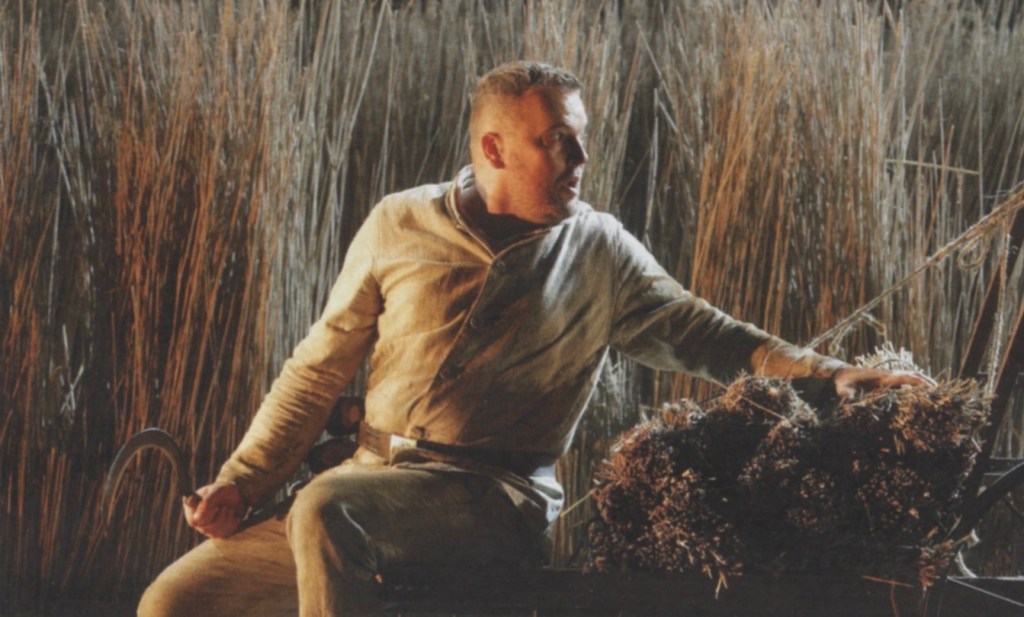

Fabrice Kebour’s lighting for David Pountney’s production of Siegfried at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2018, with Burkhard Fritz in the title role—and a strikingly lit dragon.

Working with Directors and Set Designers. Kebour recounts, “I don’t talk to the director about actual lights because it is a language that most directors don’t speak. Instead, because it’s important for the director to know what I am going to do, I explain what I want the director and the audience to feel.”

The premiere of Michael Jarrell’s Bérénice at Opéra de Paris in 2018, directed by Claus Guth with lighting by Fabrice Kebour.

Timing…. “If you are a set designer,” Constable notes, “you can build a model so that you have a miniature version of the world that everybody can work from…. With costumes, you have fittings and you can see with half-made costumes what works on specific people.”

A Holding Pattern. However, she says, “For me, all I can do is work things out on paper and in computer-generated models; but it’s only during the week or ten days before a show opens that light will meet the performers, when I am developing the lighting in front of everyone.”

“It’s tightrope-walking,” she says. “The big technical decisions are made in advance. But how a piece breathes, how it moves, where the cues are, is governed by rehearsals. It’s a bit like a holding pattern above a busy airport: You are circling, and you are learning more and more as you get close to landing.”

Creativity and Science. Constable says, “I think of myself as sitting between creativity and science. I love the logic and the use of technology to make something that is incredibly ephemeral. The toolkit available to us has grown enormously, but I often worry that we automatically regard what is new as good.”

Tomasz Konieczny as Wozzeck at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2015, in David McVicar’s production with lighting design by Paule Constable.

She notes, “I love light more than the technology.”

Stage Lighting and the Great Painters. Anthony Freud recounts, “The art of lighting design pre-dates the invention of electrical theatre lighting by several centuries: Great painters such as Caravaggio and Vermeer were masters of lighting design and light was a key engine of the drama in many of their works.”

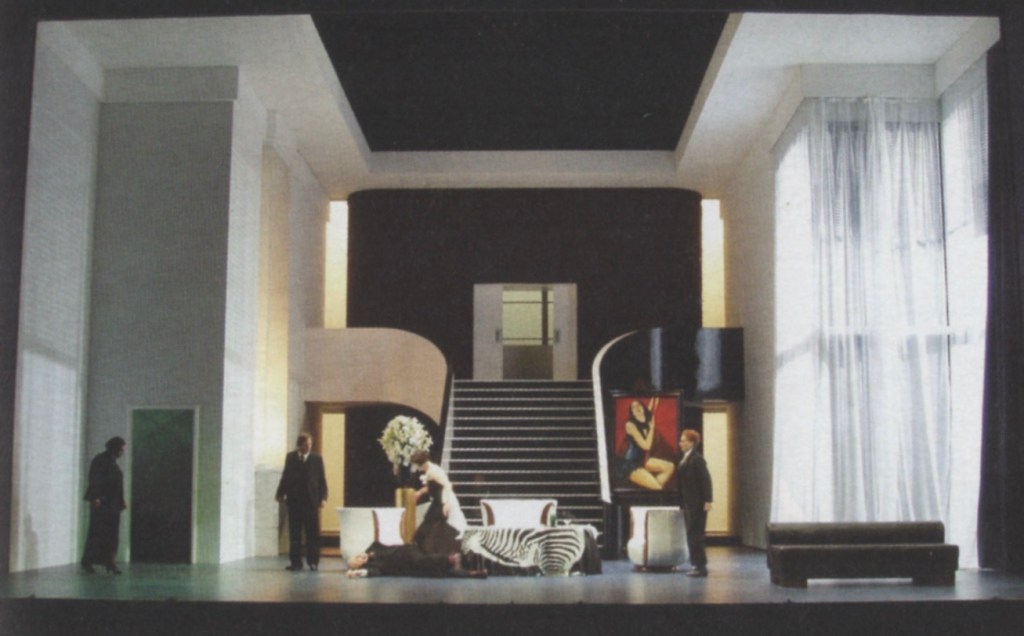

Peter Stein’s production of Lulu at La Scala in 2010, lit by Duane Schuler.

A College Exercise: Schuler recalls, “One of our exercises in college was to take a postcard of a famous painting and to draw a light plot around that postcard: How would you achieve this look if you were trying to put it onstage.”

And One for the Audience: Freud suggests, “Next time you are at a performance, try thinking about how lighting focuses the storytelling and magnifies emotion, particularly in the way it responds to the music.”

And I’ll accept that I never had sufficient talent to fulfill that teenage dream. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026