Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

HUT! HUT! PROTECTING ONE’S BRAIN PART 2

YESTERDAY, WE BEGAN GLEANING TIDBITS about the latest in football helmets. Today in Part 2, Adrian Cho delves deeper into “Softening The Blow,” AAAS Science, February 5, 2026. There’s also a related podcast “Engineering safer football helmets, and the science behind drug overdoses,” with Cho and Sarah Crespi.

A High-g Hit. Cho observes, “During a hit, a football player can experience, if only for a few milliseconds, an acceleration of up to 180 g (180 times the acceleration of gravity). The forces can rupture tissue and break bone, including in the head. A helmet’s job is to limit the head’s acceleration.”

Enter the NOCSAE. Cho continues, “Borrowing from the field of auto safety, NOCSAE [the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment] developed a test in which the helmet is placed on a dummy head, carefully designed and instrumented, and the head is dropped onto a hard surface.”

“Released in 1973,” Cho notes, “NOCSAE’s pass-fail standard spurred dramatic improvement. Helmetmakers replaced the canvas suspension with energy-absorbing foam padding and made helmets larger to give the head more room to slow down.”

A Hiatus. “Then,” Cho recounts, “innovation slowed once more—so much so that for most of his 23-year career Tom Brady, the celebrated quarterback drafted by the New England Patriots in 2000, wore a helmet that closely resembled the one worn by Hall of Famer Joe Montana of the San Francisco 49ers, who was drafted 21 years earlier. Same rigid domed shell. Same little round earholes. Same squarish face mask.”

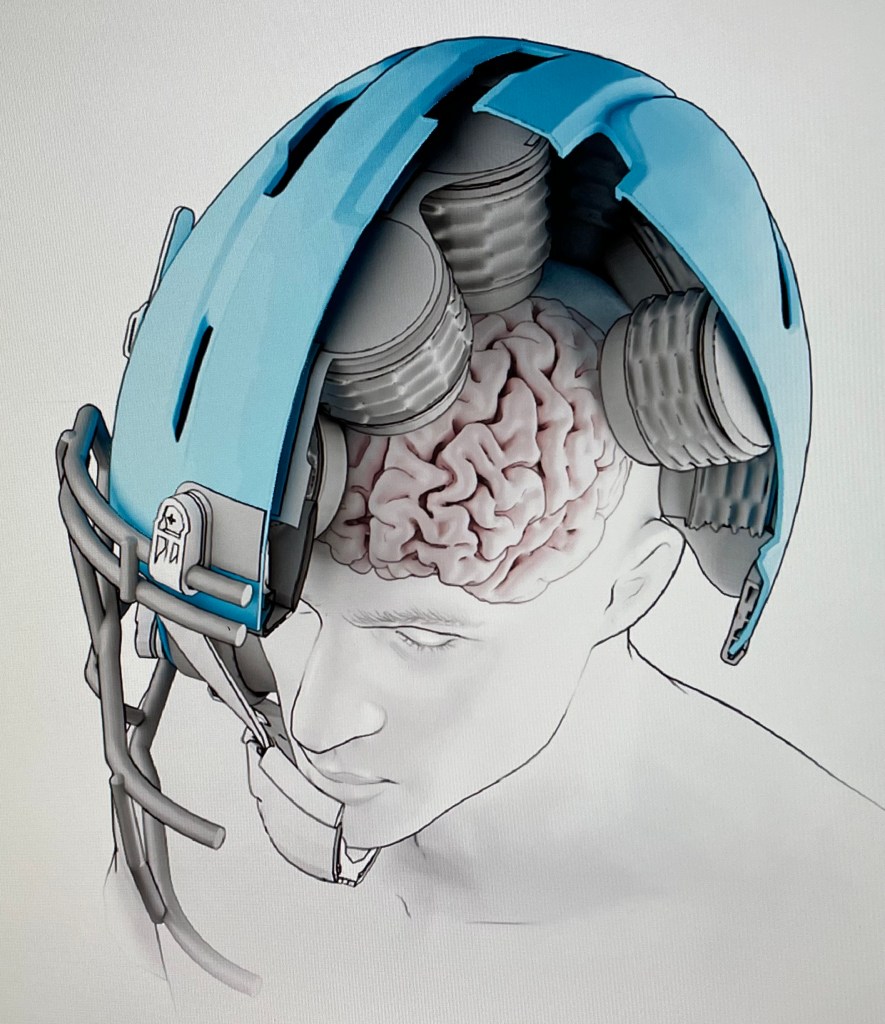

Lately, Significant Progress. Cho observes, “Both the helmet’s shell and its liner have been redesigned to crumple in a collision, absorbing energy and reducing the forces on the head and brain.”

Bigger Helmets. Continuing a decades-long trend, Cho observes, “modern helmets have also gotten bigger. The extra padded space between shell and scalp gives the head more room and time to slow down.”

This and following images from Science; some of them, accessible as videos.

Cho explains, “Molded from more pliable materials and perforated to allow for flexing, the shell of a modern football helmet bends under a blow, much like a car’s crumple zones do. Unlike the car, the helmet returns to its original shape.”

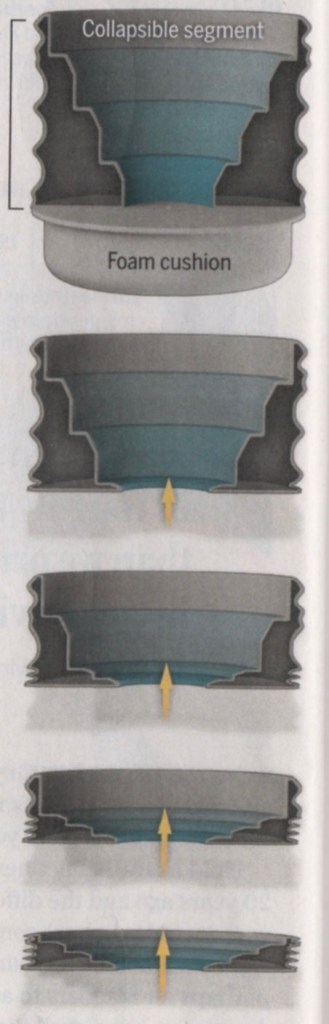

Smart 3D-Printed Padding. “Liners used to rely on foam and, sometimes, air bladders as padding,” Cho describes. “Now, many helmets employ 3D-printed liners, such as the K3D technology from KOLLIDE.”

Each pillar provides controlled collapse, reducing the head’s acceleration on impact.

Evaluating the Product. “Given the subtleties,” Cho notes, “helmet designers and engineers needed three things to improve the headgear: data on the accelerations that produce concussions, data on the sorts of hits football players experience, and a test protocol to reproduce such hits in the laboratory. And that’s what engineers at Virginia Tech and, independently, at Biocore have developed.”

Massive 2-meter pendulum tests youth helmets at Virginia Tech. Video can be accessed at the Science article.

At Virginia Tech, Cho describes, “Researchers place a helmet on a NOCSAE head, mounted on a dummy neck and bolted to a sled on rails. A magnetic latch releases a pendulum with a 15.5-kilogram bob, which swings into the head with a crisp ‘thwack!’ The procedure is repeated, striking the helmet in four spots, each at three impact speeds of up to 6.4 meters per second. For each hit researchers record the accelerations in the head and calculate the concussion risk.”

By contrast, Cho describes, “Biocore researchers reproduce those hits in the lab by placing a helmet on a dummy head and striking it at six locations and three different speeds. To mimic the unparalleled violence of the pro game, they deliver much harder blows than Virginia Tech researchers, at speeds up to 9.3 meters per second, using a battering ram powered by compressed air.”

Ann Bailey Good leads Biocore testing for the NFL. Image by Tom Cogill via Science.

Cho describes, “In the high-speed video that Biocore takes of every test, the rounded plastic end of the ram burrows into the helmet and the mechanical neck snaps over. Instruments in the head measure linear and angular accelerations, and researchers rank helmets based on their ability to limit a measure of acceleration that correlates with concussion risk.”

“The simulated hits look appalling,” Good says, “but the values for the acceleration metric have fallen by about 30% since 2015.”

Not Without Controversy. Cho observes, “Some in the helmet business question whether the Virginia Tech and Biocore testing protocols accurately represent the sorts of blows that football players experience. In particular, Nick Esayian, CEO of LIGHT, challenges the relevance of impact tests in which the helmeted head is stationary. ‘Nobody in the history of the NFL has just stood there and gotten ear-holed like that,’ Esayian says. ‘The dynamics of the testing need to better mirror the biokinetics of what really happens on the field.’ ”

Inc. recently produced a YouTube on this matter, which, honestly enough, features “Lights Helmets advertisement” during portions.

Cho concludes with, “Compared with helmets from just a few years ago, the one Kreiter [a New York Giants’ center] wears today is a marvel of engineering and technology. Exactly how much safer it is remains less clear.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026

Nick Esayian is correct in stating that real football players are not “fixed” in place as they take hits, so often the movement of their bodies during hits also absorbs some of the impact energy, but nonetheless the improved design of the helmets will help avoid or reduce brain injuries. The negative is that as players become more and more padded, harder hits become inevitable due the “invincibility” that the protection induces.

Rugby has a higher rate of concussion at 0.3% versus 0.25% for football for people over 18. But rugby rules generally preclude direct head impacts, where these are more often incidental, unlike football where the head impacts are most often more deliberate.