Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

HUT! HUT! PROTECTING ONE’S BRAIN PART 1

WHEN I WAS GROWING UP, AUTUMNAL WEEKENDS were made—or ruined—by the performance of the Cleveland Browns football team. That was the era of Lou Groza, Otto Graham, Dante Lavelli, and later Jim Brown and Frank Ryan, with plenty of my weekends celebratory indeed. I had played right tackle at Cleveland East High, one season during which we won the City Series, co-champions with the all-boys Benedictine High.

Completely independent of this, Ryan, a Ph.D. in mathematics, set one of my own Ph.D. exams at CWRU in 1969.

A Stone Wall? All this has some relevance because, as a teen fully fitted out in Blue Bombers uniform, I believed I could have survived running headlong into a stone wall.

Not very sound reasoning, of course, what with CDC data suggesting, for example, that “During 2005–2014, a total of 28 traumatic brain and spinal cord injury deaths in high school and college football were identified (2.8 deaths per year).”

No matter, for I lost interest in football: Back in 1969, what with my Ph.D. and all, we moved to St. Thomas in the Caribbean. There, mainland football made brief appearances on its single TV station one week late, and I turned to focus on international motor sports.

Duh. Long before Formula 1 crashworthiness, roll hoops, and HANS (Head and Neck Support) devices.

Which brings me, through several chicanes, to a recent AAAS Science cover story: “WHAM! Hi-tech football helmets help players take a pounding.” Here, in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, are tidbits gleaned from this Science article.

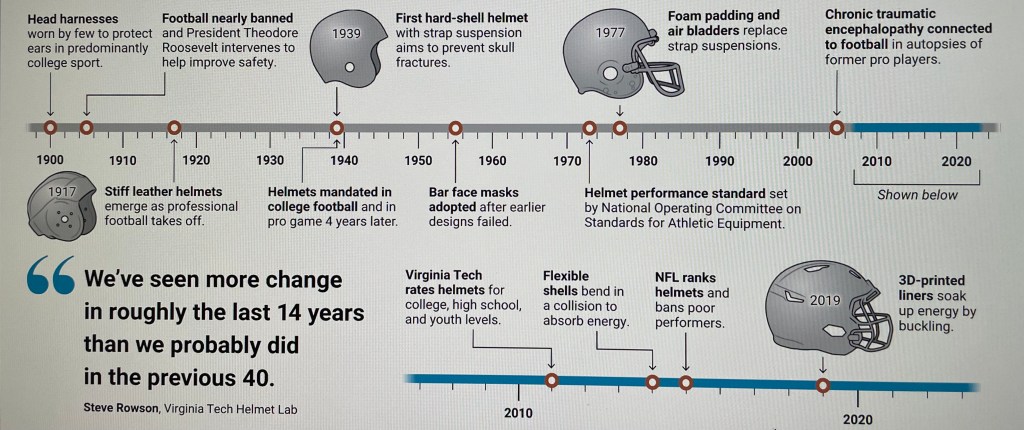

In “Softening The Blow,” AAAS Science, February 5, 2026, Adrian Cho describes, “Football helmets have improved dramatically in recent years. ‘We’ve seen more change in roughly the last 14 years than we probably did in the previous 40,’ says Steve Rowson, a biomedical engineer at Virginia Tech and director of the Virginia Tech Helmet Lab, the de facto rating body for football helmets used at college, high school, and youth levels. Ann Bailey Good, a mechanical engineer at Biocore, which tests helmets for the NFL, says, ‘From what we’ve seen in the lab, they’re definitely able to mitigate impacts much better than they could 5 or 10 years ago.’ ”

This and following images from Science, February 5, 2026.

Rowdy Origins. Cho recounts, “U.S. football emerged in the 1870s as a rowdy, brutal competition among university teams—so deadly that in 1905 then-President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to ban it. As professional football took off in the 1920s, players began to wear snug leather helmets, but they provided little protection. The first hard-shell helmet appeared in 1939. It helped prevent skull fractures but otherwise wasn’t much better. The shell was separated from the player’s head by a suspension of canvas straps, which in a hit would snap tight and transfer energy into the head.”

Concussions a Real Concern. Cho describes, “Innovation in helmets didn’t accelerate again until the 2000s, when concerns about concussions came to a crescendo. Autopsies revealed that numerous former NFL players who had exhibited behavioral and neurological problems suffered from the brain wasting of CTE. Countless parents worried whether it was safe to let their children play football, and calls arose to ban the game for youth.”

He continues, “Scientists also cannot tie those symptoms to a specific brain injury, says Rika Wright Carlsen, a mechanical and biomedical engineer at Robert Morris University who does computer simulations of the brain’s response to head blows. ‘It’s a diffuse injury, so you can’t say, “If you have a concussion, this part of the brain is damaged.” ’ Instead, she says, scientists think stretching of brain tissue triggers a cascade of biochemical signaling that leads to cell death and concussion symptoms.”

Direct vs. Oblique Hits. “Still,” Cho details, “researchers know the risk of concussion depends on the dynamics of the blow. A direct hit that causes the head to recoil without turning induces a linear acceleration and a pressure wave that, if strong enough, can tear tissue and cause a hemorrhage. However, smaller linear accelerations appear to do little damage because, being mostly water, the brain is nearly incompressible.”

“In contrast,” Cho notes, “a blow that turns the head—by striking it obliquely or causing it to pivot on the neck—produces rotational acceleration that can twist and shear the brain. Simulations show rotational accelerations can stretch tissue by 20% or more. Because of the brain’s asymmetry, which way it turns also matters. Torques in the so-called sagittal plane (nodding ‘yes’) cause smaller deformations and fewer concussions than those in the axial plane (shaking your head ‘no’).”

Akin to Automotive Controlled Collapse. Cho recounts, “Gone are the days when a football helmet consisted of a simple rigid shell lined with foam padding. Instead, new materials, designs, and technologies enable a modern helmet to flex and deform. Tests that mimic real head blows show the new features help absorb energy and limit potentially damaging accelerations within the brain.”

A blow to the head cracked the helmet of star quarterback Patrick Mahomes on a frigid day in January 2024, but it still kept him from harm. Image by Emily Curiel/The Kansas City Star via Zuma Press Wire.

Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll delve into these new technologies, not without controversies, of football head protection. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays, 2026

The sad thing is : every time they make a better helmet the coaches teach harder hits .

As a 60 + year Motocyclist I know the importance of good head gear .

-Nate