Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

IN NEED OF A DIVINE COMEDY PART 2

YESTERDAY IN PART 1 WE BEGAN sharing Eric Bulson’s review of Mary Jo Bang’s new translation of Dante’s Divina Commedia. In today’s Part 2, Bulson explores Italian (and its Tuscan dialect) and poet Bang’s efforts to bring it to modern readers.

Lost in Translation. Bulson observes, “A great deal of Dante’s remarkable repertoire of technical tricks will get lost in translation, whatever the language and whoever the translator: the chiasmuses, the neologisms, the numerical correspondences, the wordplay, all of the dazzling rhymes necessary to keep the engine of terza rima going.”

“To appreciate just one example of Dante’s feats,” Bulson offers, “here is Bang’s rendition of the tercet from Paradiso’s final canto, in which he is now face-to-face with God: ‘O Eternal Light, You who alone exist within/ Yourself, who alone know Yourself, and self-known/ And knowing, love and smile on Yourself!’ ”

“It flows,” Bulson says, “but what Dante does can’t be matched. The pileup of you and yourself and alone is meant to approximate something extraordinary that is happening in the Italian words: Etterna, intendi, intelletta, and intendente are infused with the pronoun te, ‘you,’ which is directed toward God. He is everywhere, present in the very language being employed to address him at this moment.”

English Translations. When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow rendered the first American translation of Divine Comedy, Bulson recounts, “he chose the more forgiving blank verse, which works much better in English, a rhyme-poor language without Italian’s abundance of vowel sounds at the end of words.”

“His translation, published in 1867,” Bulson notes, “was wildly popular. Since then, about 50 other American renditions of the entire poem have appeared. None is as provocative as the one that Mary Jo Bang, a poet, has been working on for the better part of two decades.”

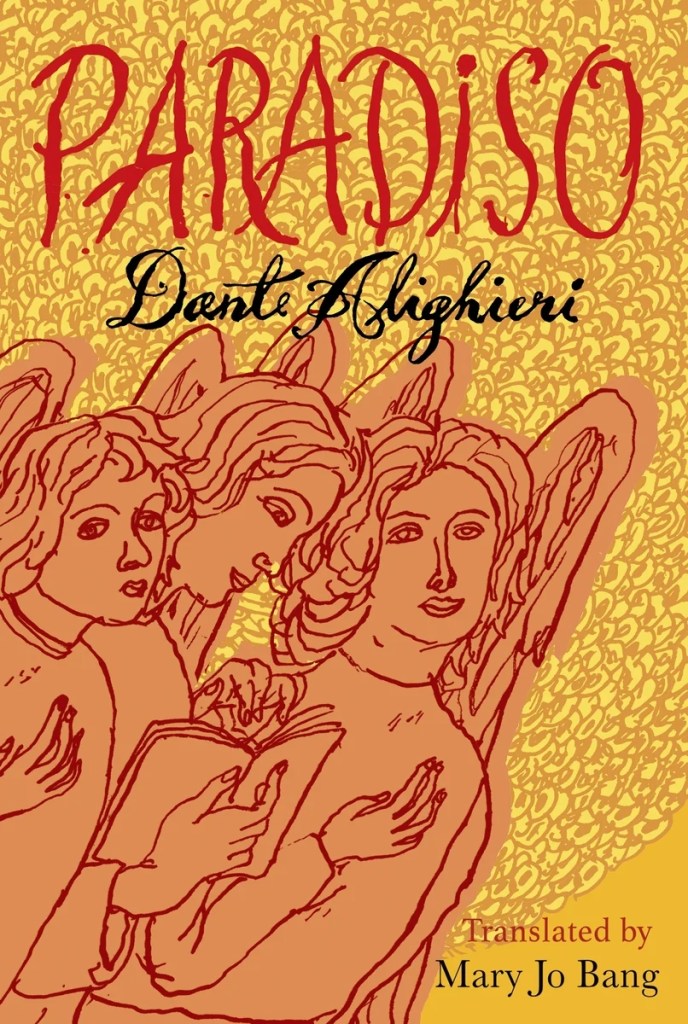

Poet Mary Jo Bang’s Paradiso.

Bang’s Methodology: Bulson observes, “Never having studied Italian, Bang saw a chance to try her hand by relying on those variations, along with Charles S. Singleton’s translation (already on her shelf). The 47 variations mostly struck her as formal and ‘elevated,’ and she was curious to discover how contemporary English would sound.”

“In the process,” Bulson says, “she arrived at something fresh: ‘Stopped mid-motion in the middle/ Of what we call our life,’ her tercet began, conveying an abrupt jolt, as if a roller coaster was kicking into gear, and then went on: ‘I looked up and saw no sky—/ Only a dense cage of leaf, tree, and twig. I was lost.’ ”

Referencing Ray Bradbury, Elton John, Shakespeare, and Led Zeppelin. As other examples, Bulson observes, “Bang mixes in nods to the more contemporaneous references she’s used. An image of reflecting light that ‘bounces up, / Like a rocket man who longs to come back’ is accompanied, for example, by a citation to both a 1951 Ray Bradbury short story and the Elton John song ‘Rocket Man.’ ”

Bulson continues, “Commenting on the line ‘Don’t be like a feather in each wind’ as a metaphor for inconstancy, she refers to an echo not just in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale but also in Led Zeppelin’s ‘All My Love.’ This poem, she conveys, isn’t frozen in time….”

Indeed, art should be etterna. Thanks, Eric Bulson and Mary Jo Bang for this. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026

Related

Information

This entry was posted on January 22, 2026 by simanaitissays in I Usta be an Editor Y'Know and tagged "What Dante Is Trying To Tell Us" Eric Bulson "The Atlantic" (review of Bang's translation), Bang's translation includes touches of Bradbury/Elton John/Shakekspeare/Led Zeppelin, Dante exiled from Florence (yet composed in Tuscan dialect), Dante's "Divina Commedia" "Inferno" "Purgatorio" "Paradiso", Dante's "Divine Comedy" translated by Mary Jo Bang, Dante's terza-rima complex rhyming scheme, Italian: lots of vowel endings (rhyming), Mary Jo Bang poet strives to use contemporary English in translation, Mary Jo Bang: poem not frozen in time.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-kTaCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012