Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

IN NEED OF A DIVINE COMEDY PART 1

READERS BACK TO 2017 MAY RECALL “Dante’s Inferno, a Destination Guide;” this, concerning the first of three parts of Divina Commedia (the other two, Purgatorio and Paradiso).

Durante degli Alighieri, known as Dante, c. 1265–1321, Italian poet, writer, and philosopher. Renowned as the Father of the Italian language. A posthumous portrait by Sandro Botticelli, 1495, via Wikipedia.

Given plenty of today’s hellish goings-on, I felt compelled to read Eric Bulson’s “What Dante Is Trying To Tell Us,” The Atlantic, January 2, 2026: In particular, “A colloquial translation of Paradiso might make people actually read it.”

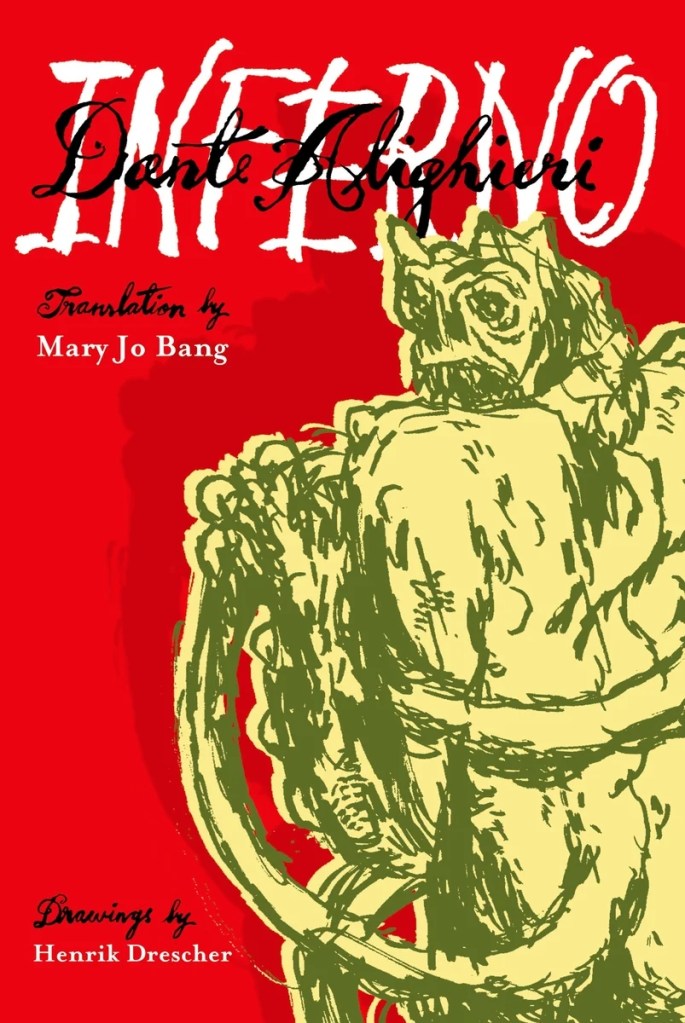

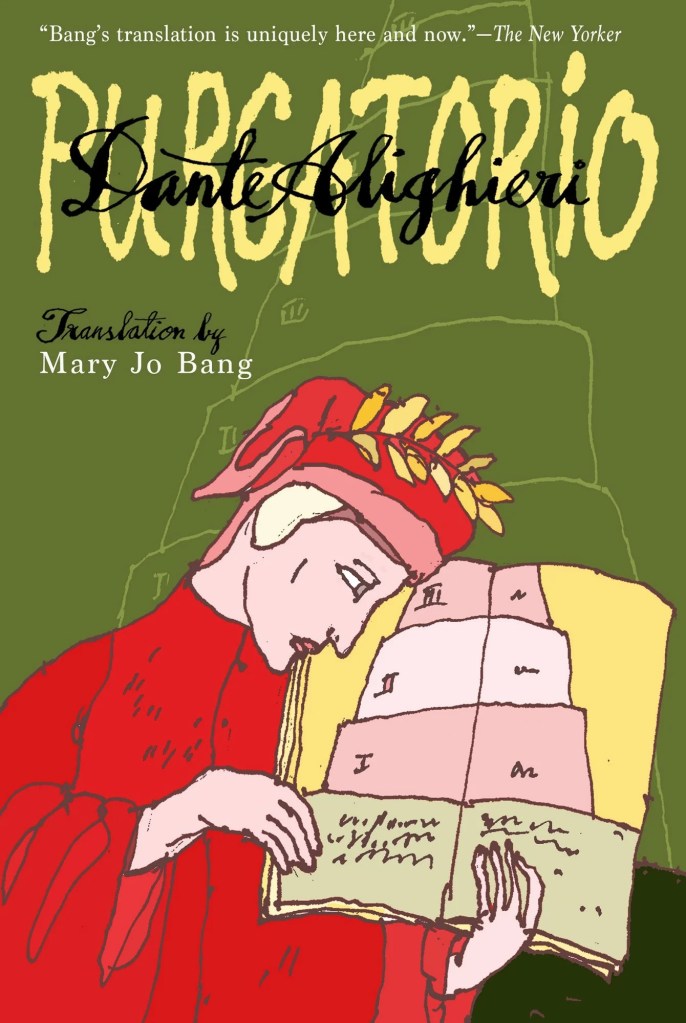

Well, I can’t say that for sure, but I certainly can glean tidbits, here in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow, from Bulson’s most informative review of poet Mary Jo Bang’s renderings of Divina Commedia. “Following on her Inferno (2012) and Purgatorio (2021),” Bulson writes, “Bang’s Paradiso has arrived at a moment of national turmoil, and sets out to make a vision of hope and humility accessible to all in an unusual way.”

Dante’s Faction-Ridden Florence. Bulson recounts, “During the years that Dante worked on the Divine Comedy—1307 to 1321, the last decade and a half of his life—he was exiled from his faction-ridden hometown of Florence. Dante, who vehemently opposed the papacy’s desire for secular power, had been charged with financial corruption, a politically motivated accusation, and the threat of being burned at the stake if he returned hung over him.”

Dante Alighieri, detail from Luca Signorelli‘s fresco in the Chapel of San Brizio, Orvieto Cathedral. This and following images from Wikipedia.

“A party of one,” Bulson relates, “as he later called himself, he wandered from court to court, living off the generosity of a few patrons. He never set foot in Florence again.”

The Conventional Tuscan Commedia. Despite being exiled from Florence—and contrary to the literary practice of the era—Dante chose to compose Commedia in his native Tuscan dialect, not the usual Latin.

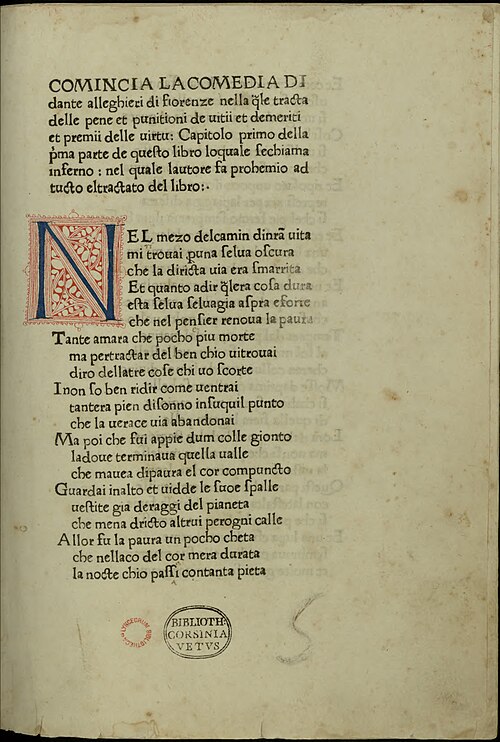

Divina Commedia, 1472. Image from the BEIC digital library and uploaded in partnership with BEIC Foundation.

What’s more, Bulson reminds us that Dante’s poem has a particularly complex “terza-rima scheme (in which the last word in the second line of a tercet provides the first and third rhyme of the next tercet).” Check this out in the example above.

Such a scheme makes Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter rhyming look simple indeed. (My own modest example: “And now ’tis time that I shall off and git/ To ponder all the nonsense I’ve just writ.”)

Dante on the national side of the Italian 2 euro coin. Image from European Central Bank via Wikipedia.

Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll learn more of translating Dante’s remarkable tale. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026

Related

Information

This entry was posted on January 21, 2026 by simanaitissays in I Usta be an Editor Y'Know and tagged "What Dante Is Trying To Tell Us" Eric Bulson "The Atlantic" (review of Bang's translation), Bang's translation includes touches of Bradbury/Elton John/Shakekspeare/Led Zeppelin, Dante exiled from Florence (yet composed in Tuscan dialect), Dante's "Divina Commedia" "Inferno" "Purgatorio" "Paradiso", Dante's "Divine Comedy" translated by Mary Jo Bang, Dante's terza-rima complex rhyming scheme, Italian: lots of vowel endings (rhyming), Mary Jo Bang poet strives to use contemporary English in translation, Mary Jo Bang: poem not frozen in time.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-kSMCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012