Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

LYNN PECKTAL’S DESIGNING AND PAINTING FOR THE THEATRE PART 2

YESTERDAY IN PART 1, WE SET THE STAGE offered by Lynn Pecktal’s seminal book on theater set design. The more I examined his book, the more I understood that my youthful dream of joining his profession wasn’t gonna happen. Alas, talents were required, none of which I exhibited to any significant degree. However, set design is still fun to explore, and I hope you find it fun as well.

Summarized here are several of my non-talents.

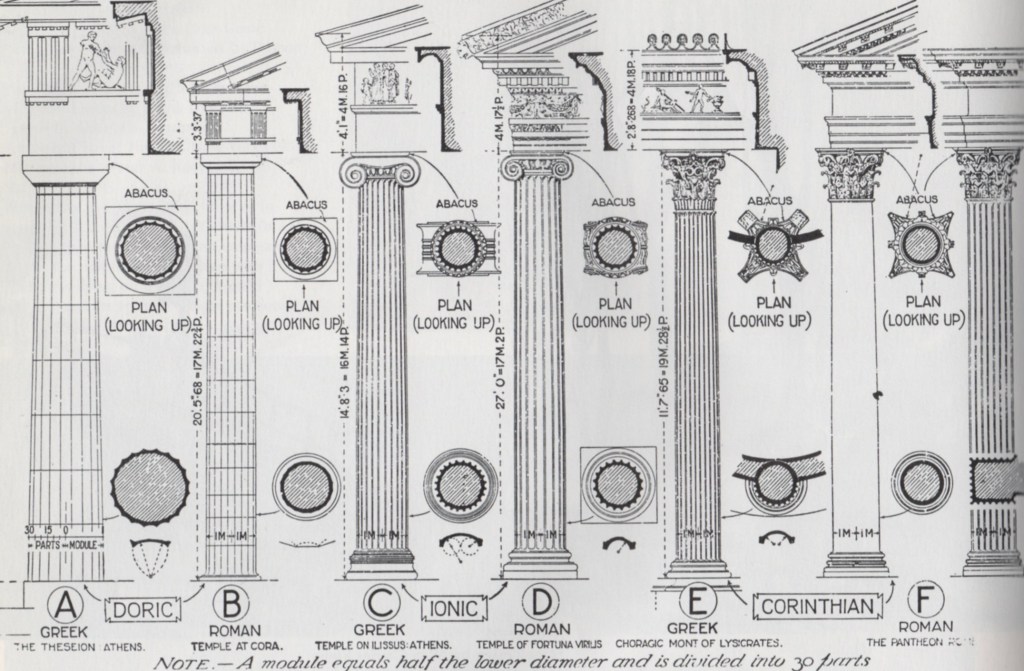

Architect. Pecktal says, “Every theatre designer and scenic artist is expected to be familiar with the orders of architecture.” He cites Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius, first century B.C., as setting up “specific proportions on the Greek orders, defining the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.”

Comparative Greek and Roman Orders of Architecture. This and other images from Designing and Painting for the Theatre.

“An order,” Pecktal explains, “is made up of a column (base, shaft, and capital) and entablature (architrave, frieze, and cornice). Each order varies as to proportions, ornament, molding, and details, with the capital of the column being the most characteristic feature of each one.”

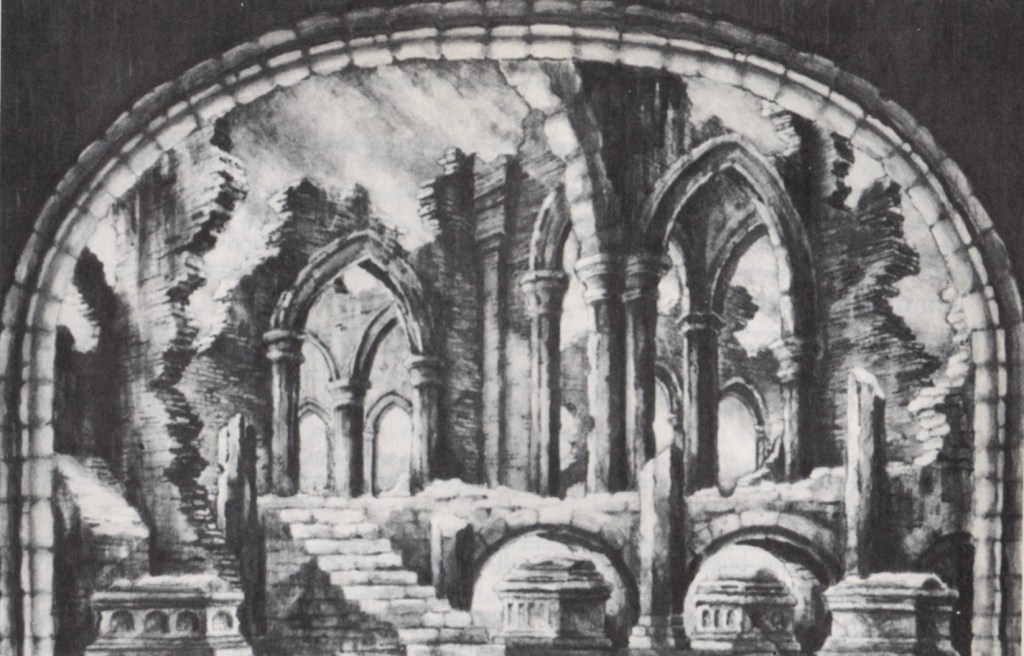

Columns galore. Stage Design for Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia Di Lammermoor, Act III, Scene 2, by Lynn Pecktal; Teatro Municipal Santiago, Chile, 1970.

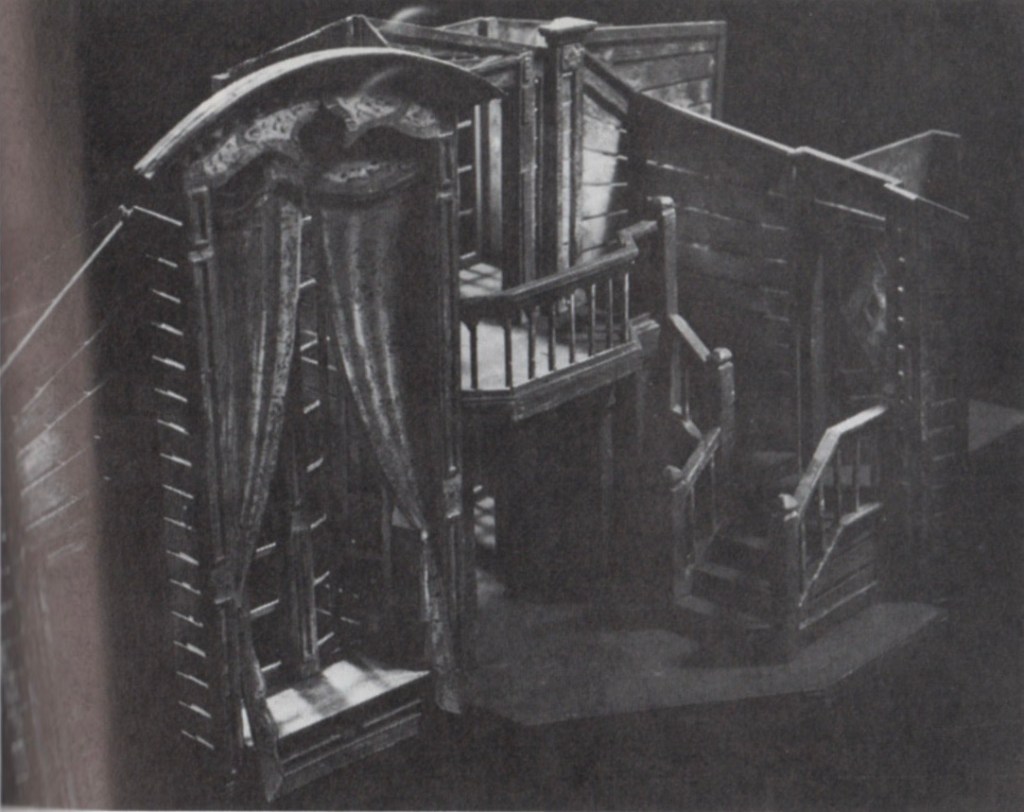

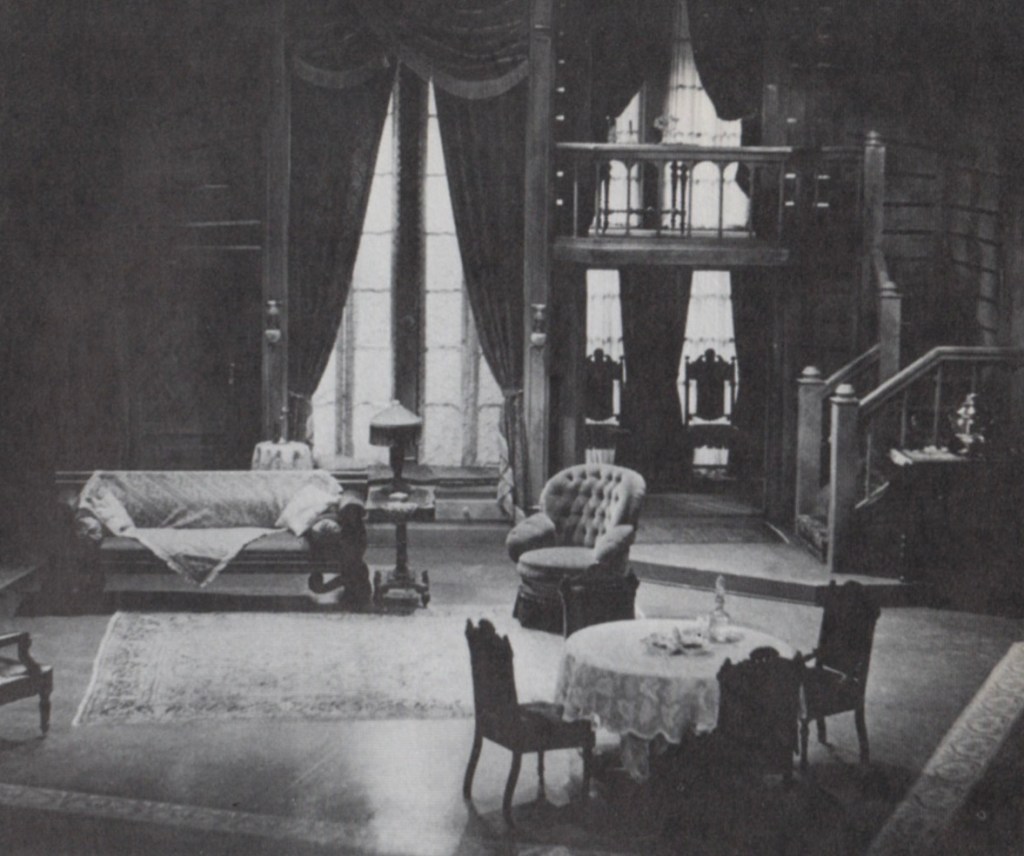

Draftsman and Modeler. Often a scene design begins with rough sketches and then elevation drawings evolving into a model, “the most widely accepted scale for building models is 1/2 inch = 1 foot, the same scale in which the designers elevations and plans are drawn.”

A model and setting by Elmon Webb and Virginia Dancy for Maxim Gorky’s Yegor Bulichov; Long Wharf Theatre, New Haven, Connecticut, 1970.

Pecktal notes the importance of a model being compatible with the theatre layout, theatergoer views, and stage dimensions.

Painter. Pecktal’s book devotes a chapter to Scenic Painting Techniques and another to Paints, Binders, Glues, and Equipment. Early on, he describes Qualifications for Memberships in All Classifications of Local 829 of the United Scenic Artists Union.

“Several weeks prior to all this testing,” he describes, “the applicant is assigned a show to design as a ‘home project,’ which may include set designs, color elevations, working drawings, and a model.”

Painting on the Home Project for the Scenic Artists Examination. Photo by Lynn Pecktal.

Hope Auerbach and Sue Chapman are “shown working on part of the assigned home project, a 4 foot by 6 foot painting of an interior on muslin. Subjects including in the supplied drawing are brocade wallpaper, marble fireplace with gilt framed mirror above, carved-wooden folding screen with tapestry, metal fire screen, porcelain vase with flowers, fabric draped over screen, and a flagstone hearth.”

Plenty of paint cans are evident.

And Then There’s The Pounce Wheel. Pecktal describes, “The pounce wheel is the most essential item…. This small prickling wheel is run over the lines of a design [on what looks like butcher paper], leaving small holes so the drawing can be transferred onto a surface (fabric, wood, or whatever) by rubbing a bag of powered charcoal over the paper…. The smallest-size wheel, for instance, is deal for pricking minute ornamental detail.”

Above, a variety of 17th- and 18th-century ornamentals. Below, scenic artist Ethel Green prepares a pounce paper pattern for transferring a lion’s image from its 1/2-in.-scale paint elevation by Carl Toms’ Il Puritani, 1973. Photograph by Lynn Pecktal

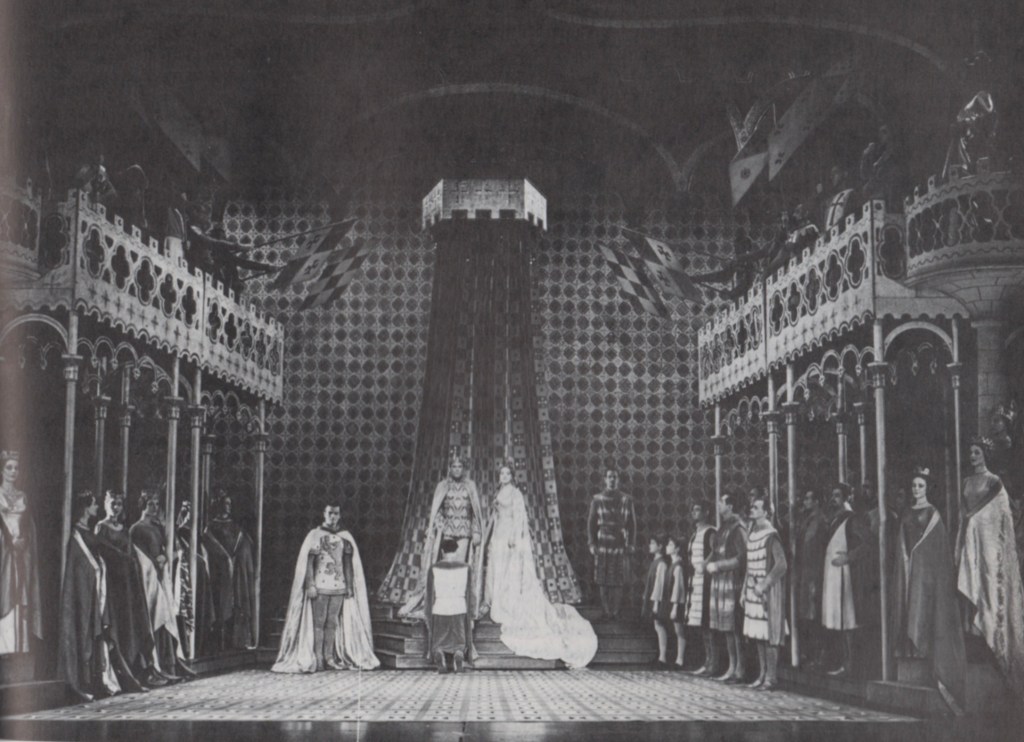

Ultimate Productions. Scenery can be as elaborate as Oliver Smith’s heraldry for Camelot or as unconventionally immersive as the Lee’s Candide.

Above, Camelot, setting by Oliver Smith, Majestic Theatre, New York, 1960. Below, Candide, settings and costumes by Eugene Lee and Franne Lee, Broadway Theatre, New York, 1974. Photographs by Friedman-Abeles.

I suspect there was plenty of pouncing in forming Camelot’s intricacies. By contrast, Pecktal observes, “Eugene Lee revamped the Broadway Theatre (a proscenium house) into one large playing arena with spectators seated on benches and stools. Planked platforms and levels form various patterns throughout the house The orchestra is shown in the foreground.”

And you can bet that theatergoers had a fine time at both venues. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026