Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

STROLLING THE STRAND—MIND THE PRIMEVAL HIPPOPOTAMI PART 2

YESTERDAY, WE BEGAN GLEANING TIDBITS from Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s LRB review of Geoff Browell and Eileen Chanin’s The Strand: A Biography. Today in Part 2, we continue the fun.

Nationalizing the Monasteries. Remember those bishops reaping profits from tenements built along the Strand? Between 1536 and 1541, Henry VIII came up with a scheme for diverting these rents into his own doublet and bombasted hose: He nationalized the bishops’ Strand properties as well as the monasteries, priories, convents, and friaries. His rationale was being Supreme Head of the Church of England. (Just in case you’re seeking another reason for separation of church and state….)

An unidentified tailor wearing doublet and bombasted hose in Giovanni Battista Moroni‘s portrait, c. 1570. Image from Wikipedia.

Graham recounts in her LRB article, “The dissolution of the monasteries had transferred ‘the wealth of the great religious houses to a Protestant landed elite’ and the Strand became a ‘museum mile’, with its eleven great mansions displaying the finest antiquities and artworks.”

The last of the Strand palaces, Northumberland Place, was demolished in 1874. Bridgeman Image via Country Life.

“The earl of Leicester,” she notes, “rebuilt what had been the episcopal palace of the bishops of Exeter, filling it with paintings and tapestries. There were some brutal evictions. Robert Cecil used ‘strong-arm tactics’ to acquire land from the bishop of Durham and hastily evicted the sitting tenant, Walter Raleigh.”

Civil War and Charles II’s Return. Graham describes that the Civil War (and Oliver Cromwell) ended the Strand’s period as a Renaissance idyll. “Somerset House,” she recounts, “became a barracks for Parliamentarian soldiers. The other great houses ‘never recovered from the damage’ of the war and the interregnum. But because of its width and centrality, the Strand retained its ceremonial significance: the diarist Thomas Rugge described Charles II’s triumphant return along the Strand to Whitehall, to the sound of ‘such shouting as the oldest man alive never heard the like’. ”

Don’t Travel Without Your Dollond. “After the Italianate elegance of earlier centuries,” Graham says, “the 18th-century Strand became ‘a hub of knowledge and innovation’, with instrument makers catering to every new scientific pursuit. Jonathan Sisson’s workshop had a high reputation for mathematical instruments; John and Peter Dollond, opticians, made the first telescope to be encased in mahogany (Captain Cook always travelled with his ‘Dollond’).”

A vintage Dollond telescope. Image from New Jersey Herald.

Kit-Kat Club. Graham describes, “Samuel Reiss’s Grand Cigar Divan replaced the Fountain Tavern, where the Kit-Cat Club used to meet: entry was a shilling and sixpence (for coffee and a cigar), or for 21 shillings a year you could drink as much coffee as you liked. ‘These meeting places,’ the authors write, ‘became the libraries and colleges from which information expanded.’ They were hubs of free speech.”

Lighting the Strand. Graham recounts, “The journalist John Hollingshead opened the Gaiety Theatre in 1868, its façade illuminated with dazzling electric lighting.” She also mentions the “Great Stink” of ten years before (which sure sounds like a topic for another day).

The Game is Afoot. “The first issue of The Strand Magazine,” Graham relates, “was published in 1891, with a cover illustration by George Haité…. Readers queued round the block outside the paper’s office in Burleigh Street for the next installment of The Hound of the Baskervilles.”

Image from Marshall Rare Books.

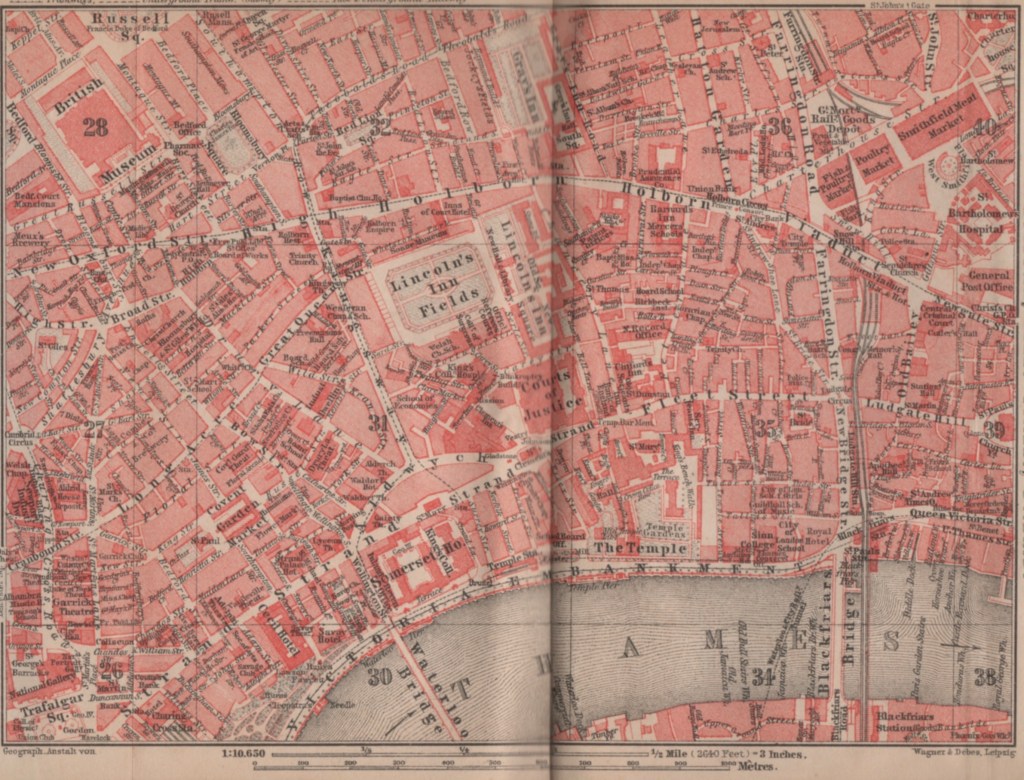

The “Centre of the World.” “In 1904 in one twelve-hour period,” Graham recounts, “observers recorded 2582 omnibuses, 1285 hansom cabs, 790 trade vehicles, 286 four-wheelers, 228 bicycles, 112 carriages and 93 barrows passing along the Strand.”

Image from Baedeker’s London, 1911.

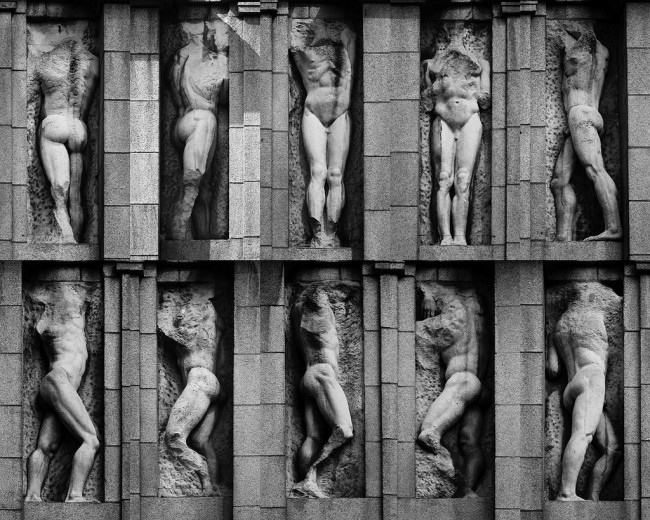

What’s more, she notes, “The Evening Standard worried that Jacob Epstein’s eighteen nude statues on the new British Medical Association building were ‘laid bare to the gaze of all classes, young and old, in perhaps the busiest thoroughfare of the Metropolis of the world’. ‘They are a form of statuary,’ the Standard added, ‘which no careful father would wish his daughter and no discriminating young man would wish his fiancée to see.’ ”

Harrumph.

Removing “Protruding Parts”…. “They were still causing outrage in 1937,” Graham notes, “after the building became the Rhodesian High Commission, when protruding parts were removed supposedly ‘as a measure of public safety’, much to Epstein’s outrage.”

The Future? Graham concludes, “Among the scenarios the authors imagine for the future of the Strand (including submersion under 200 feet of water), they conjure a vision of the street ‘at the heart of a regenerated and confident London … in the midst of a technological and humanist renewal’. ”

One might also ponder where those protruding parts ended up. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026