Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

STROLLING THE STRAND—MIND THE PRIMEVAL HIPPOPOTAMI PART 1

IN READING “BUSIEST THOROUGHFARE OF THE METROPOLIS OF THE WORLD,” by Ysenda Maxtone Graham in London Review of Books, December 4, 2025, I am reminded of my sole phrase of Swahili: “Kiboko anaharibu kibanda chetu,” “A hippo is destroying our hut.”

In her LRB review of The Strand: A Biography, Graham begins, “After reading Geoff Browell and Eileen Chanin’s concise history of the Strand, you will never walk down that street again without thinking of the hippopotami that wallowed in a primeval swamp at the Trafalgar Square end. The bones of the hippos, as well as those of ‘herds of straight-tusked elephants and prides of lions’, were unearthed in 1957, when Uganda House was being built.”

This is one of many choice tidbits gleaned from Grahams’s review. No surprise, everything works out to Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow.

The Strand: A Biography, by Geoff Browell and Eileen Chanin, Manchester University Press, 2025.

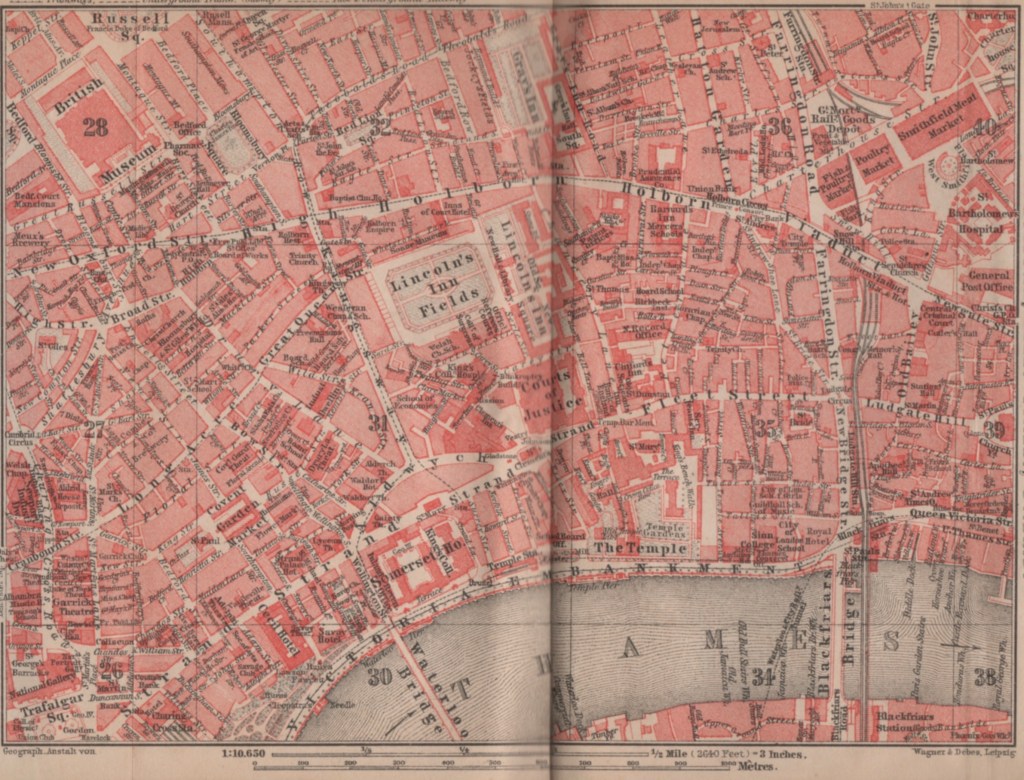

Lundenwic. Graham discusses an Anglo-Saxon town not discovered until the 1980s: “Lundenwic emerged two centuries after the Romans retreated from Britain and covered the area now bordered by Long Acre and Kingsway to the north. The authors suggest that superstition might have led the Anglo-Saxons to build outside the old Roman walls: did they imagine ghosts as they ‘surveyed from afar the colossal wreck, boundless and bare, of the Roman amphitheatre, and of the collapsed basilica and forum’? Perhaps they simply found it more convenient.”

“Archaeological finds,” Graham continues, “show that Lundenwic was a cosmopolitan town of around nine thousand inhabitants at its peak and ‘alive with busy craft industries’, including the carving of bone and antler and textile manufacture using wool or flax.”

Lundenburh. “With the reassuring predictability of a children’s history book,” Graham recounts, “the next historic event discussed is the pillaging of the Strand by the Vikings.”

The Alfred Jewel, in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, commissioned by Alfred; probably a pointer to aid reading. Image by Mkooiman via Wikipedia.

“In 886,” Graham recounts, “King Alfred reoccupied Lundenwic and rechristened it Lundenburh. The Strand is recorded in charters as the Akemannestrete—the road to Bath—and took a sharp right at a hamlet called Cierring (Charing Cross), went up what is now the Haymarket and carried on west past the Ritz and Harrods.”

The Stronde. Graham describes that the Stronde appears in records from 1185, “so named because of its proximity to the Thames.”

Chaucer’s Time. “By 1400,” Graham recounts, “the great medieval flourishing of the Strand had begun. At the time, it was the first road above the northern bank of the Thames; its newly built palaces, most of them the London seats of diocesan bishops, had gardens that spanned the full acreage down to the river, and water gates for access by boat. With great canniness, the bishops ensured that their houses had a row of tenements or ‘rents’ on the Strand, raking in money for their diocese.”

A drawing from the 1491/2 Pynson edition of The Canterbury Tales. Image refined by DemonDays64 via Wikipedia.

And, sure enough, when Geoffrey Chaucer composed The Canterbury Tales between 1387 and 1400, he included the line “And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes….”

Tomorrow in Part 2, 140 years later Henry VIII comes up with a scheme for diverting bishops’ rents—he nationalizes the monasteries. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2026