Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

CELEBRATING BEN FRANKLIN, SCIENTIST

LET US COUNTER THESE DAYS OF LAMENTABLY UNDERACHIEVING POLITICIANS by celebrating Benjamin Franklin, a statesman—and scientist—of the highest order. Ferdinand Mount’s “His Very Variousness,” London Review of Books, December 4, 2025, reviews two books about him: Kevin J. Hayes’ Undaunted Mind: The Intellectual Life of Benjamin Franklin and Richard Munson’s Ingenious: A Biography of Benjamin Franklin, Scientist.

Undaunted Mind: The Intellectual Life of Benjamin Franklin, by Kevin J. Hayes, Oxford University Press, 2025.

Ingenious: A Biography of Benjamin Franklin, Scientist, by Richard Munson, W.W. Norton & Company, 2024.

Here are tidbits gleaned from these two books, their LRB review, and my usual Internet sleuthing.

A Bracing A.M. “Air Bath.” Ferdinand Mount describes, “In his middle age, during the seventeen years he lodged for long periods at 36 Craven Street, just off the Strand, Benjamin Franklin became addicted to what he called his ‘air bath’. Every morning, he would strip naked, throw open the windows and pass half an hour reading or writing in the nude, before dossing down refreshed for another hour or so, sometimes answering the door in the buff to startled postmen.”

“Franklin was a total immerser;” Mount continues, “he bathed in the cold morning breeze, just as he plunged into the freezing Thames, or wallowed in the company of London wags and wits, or, above all, absorbed himself in his scientific investigations.”

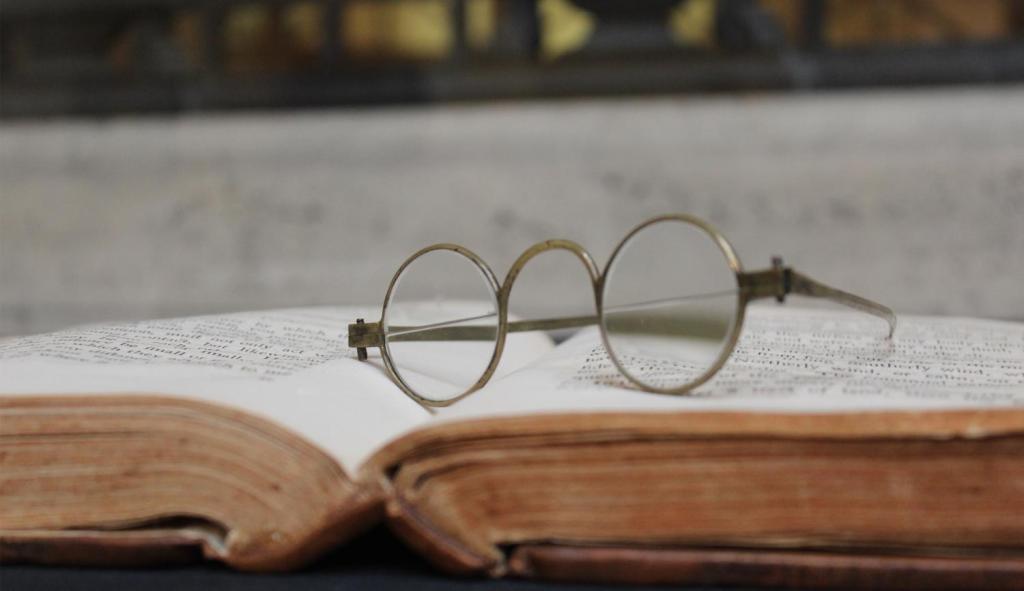

A Talented Dilettante? My early schooling, and I bet yours too, cited Franklin’s invention of bifocals, his flying a kite in a thunderstorm, and maybe his stove. But they left me with a feeling of his being a talented dilettante, not really a scientist.

“Tired of switching between two pairs of eyeglasses, he invented ‘double spectacles.’ ” Image and caption from The Franklin Institute via Wikipedia.

As Mount observes, “Yet, perhaps because of his very variousness, Franklin’s biographers often dismiss these devices and discoveries as a string of hobbies, so many diversions from his statesmanship. Gordon Wood, in his Encyclopaedia Britannica article, asserts that ‘Franklin never thought science was as important as public service.’ More patronising still, Franklin is presented as a tinkerer who didn’t really understand the science.”

Mount continues, “Even the latest addition, Kevin Hayes’s Undaunted Mind, devotes only 20 of 380 pages to what some of these authors seem to think of as Ben’s Stinks. It is Richard Munson’s mission to explode these delusions, and he does so with ease and some elegance in his exemplary short [288 pp.] Life, which concentrates on Franklin’s scientific endeavours.”

Franklin, Up There With Newton. Continuing this theme, Mount cites, “Munson points out the ways in which the great scientists of Franklin’s time (and ours) have paid tribute to his originality. Joseph Priestley in his History and Present State of Electricity (1767) declared Franklin’s discoveries ‘the greatest, perhaps, that have been made in the whole compass of philosophy since the time of Sir Isaac Newton’. Priestley’s essay is largely a hymn to Franklin, not only for his discoveries but for the honesty and diffidence of his methods.”

Several Franklin Contributions. Mount observes, “Franklin created a new vocabulary to describe the way electricity works: conductor and insulator, condenser and battery, plus and minus charges. It’s not simply that he taught the world how to rig up a lightning conductor (he installed one on his own house and another on St Paul’s Cathedral). He was master of the theory too. Kant called him ‘the Prometheus of recent times’. It was because he was already an international superstar of science that this provincial printer was invited into the political counsels of great men.”

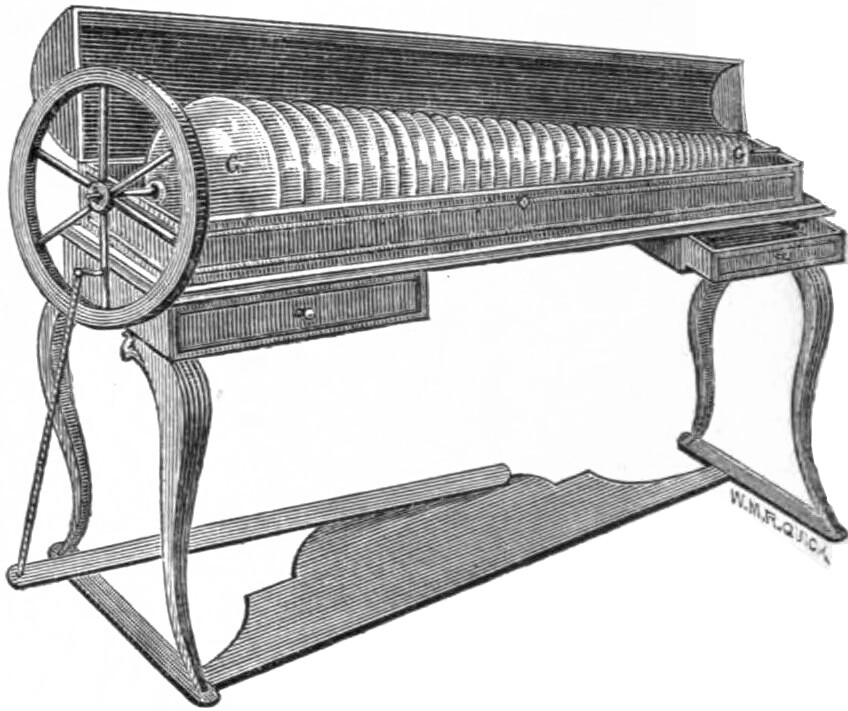

Wide-Ranging Interests. Mount notes, “The invention of his which bequeathed the most pleasure to posterity was Franklin’s armonica—a development of the old pastime of rubbing wet fingers around the rims of different-sized glasses to produce notes of different pitch.”

A glass harmonica, c. 1900. Image from George Grove (editor of his eponymous music dictionary) via Wikipedia.

Mount continues the instrument’s description: “Franklin’s treadle spun the glasses, allowing the player to produce the most delightful melodies and attracting composers from Mozart and Beethoven to Saint-Saëns and Richard Strauss to write music for the instrument. I once heard Bruno Hoffmann, the most celebrated modern exponent, play his version of Franklin’s glass armonica. The sound was unforgettable – piercing, melancholy, otherworldly.”

Mount says of Franklin, “He was a theorist of everything—swimming, for example. As a boy, he taught himself the different strokes from Melchisédech Thévenot’s Art de nager, then devised flippers for his feet (later adopted by Jacques Cousteau) and paddles for his hands.”

Open to Experience. “All his life,” Mount recounts, “he remained as open to experience as his bare bottom was to the chilly winds of Craven Street.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025