Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

EXPO TIDBITS PART 1

IT TURNS OUT I’VE VISITED SEVERAL WORLD EXPOSITIONS (or their sites) as well as written about some others. What with our Semiquincentennial coming soon, this seems a good time to glean tidbits about previous expos, in no particular order. No surprise, there are enough of them to warrant Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow.

Two in Philly. The 1876 Centennial and 1926 Sesquicentennial were both held in Philadelphia, historically so important in our country’s founding. On the other hand, this reminds me of memorable comments from W.C. Fields: “I once spent a year in Philadelphia; I think it was on a Sunday.” And his epitaph: “All things considered, I’d rather be in Philadelphia.” There’s also H.L. Mencken’s quoting Miss Nellie, a highly respected Baltimore madam, who told him, “Henry, nobody in their right mind goes to Philadelphia.”

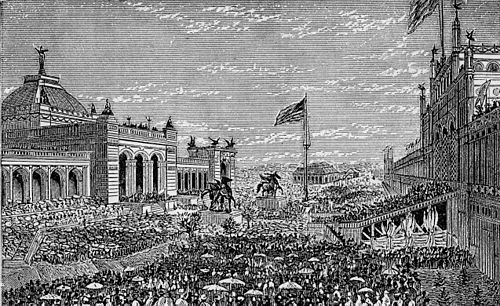

Philadelphia 1876. Wikipedia notes, “The Centennial International Exhibition, officially the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine [quite the catchy official moniker, eh?] was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876.”

Image by James D. McCabe via Wikipedia.

This was the first official world’s fair to be held in the United States and offered lots of innovation including the telephone, the typewriter, the sewing machine, a slice of the 5 3/4-in. cable supporting the Brooklyn Bridge, the right arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty, and a Centennial Monorail.

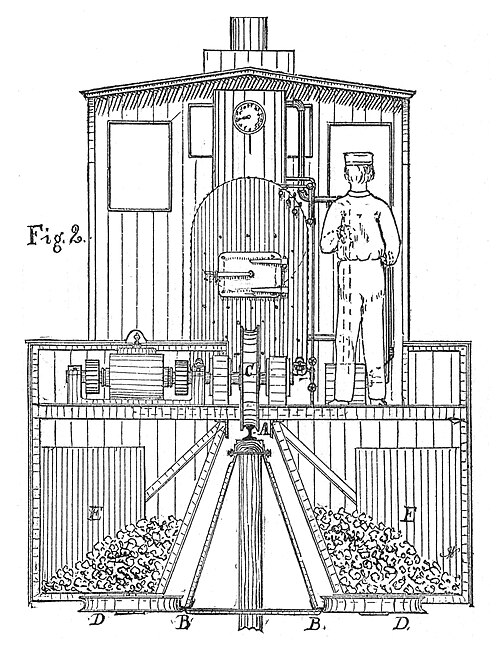

The Centennial Monorail was propelled by a steam locomotive. Image from Scientific American Suppl. II.33, August 12, 1876 via Wikipedia.

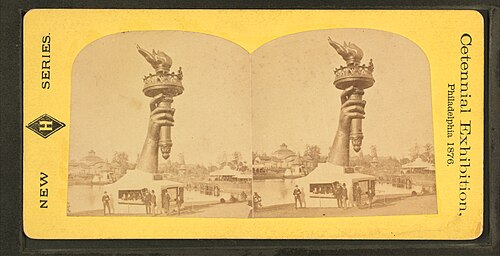

Why Only Her Right Arm and Torch? Wikipedia recounts, “The idea for the statue was conceived in 1865, when the French historian and abolitionist Édouard de Laboulaye proposed a monument to commemorate the upcoming centennial of U.S. independence (1876), the perseverance of American democracy and the liberation of the nation’s slaves. The Franco-Prussian War delayed progress until 1875, when Laboulaye proposed that the people of France finance the statue and the United States provide the site and build the pedestal. Bartholdi completed the head and the torch-bearing arm before the statue was fully designed, and these pieces were exhibited for publicity at international expositions.”

Stereoscopic image of right arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty.

Indeed, Wikipedia notes, “For a fee of 50 cents [a fair piece of change in 1876, worth $15.14 today!], visitors could climb the ladder to the balcony, and the money raised this way was used to fund the pedestal for the statue.” The full installation on Liberty Island was dedicated on October 28, 1886.

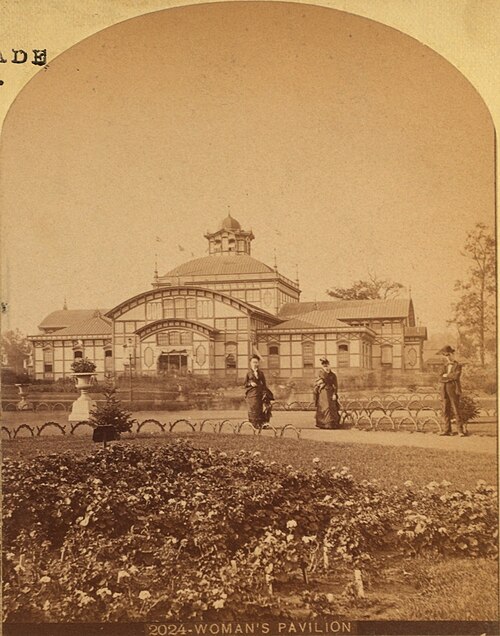

The Woman’s Pavillion. “The Women’s Pavilion,” Wikipedia recounts, “was the first structure at an international exposition to highlight the work of women, with exhibits created and operated by women. Female organizers drew upon deep-rooted traditions of separatism and sorority in planning, fundraising, and managing a pavilion devoted entirely to the artistic and industrial pursuits of their gender.”

Wikipedia continues, “Their overarching goal was to advance women’s social, economic, and legal standing, abolish restrictions discriminating against their gender, encourage sexual harmony, and gain influence, leverage, and freedom for all women in and outside of the home by increasing women’s confidence and ability to choose.”

What novel concepts for 1876. What novel concepts for today.

Philadelphia 1926. The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition was the idea of John Wanamaker; he, the 35th United States Postmaster General and also founder of Philadelphia’s first department store.

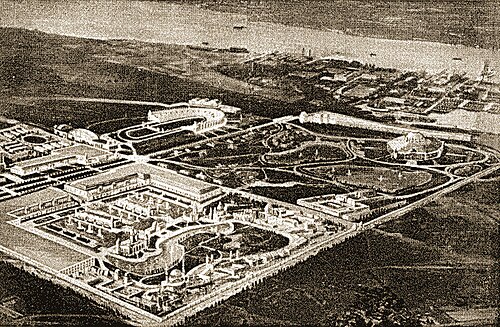

1926 Sesquicenntennial International Exposition. This and the following image from Wikipedia.

Wikipedia observes of the 1920s, “At the time Philadelphia was a booming city, in terms of size and opportunity; however, it suffered from corruption on political and financial fronts. Wanamaker was well aware of the city’s corruption, and believed a fair could redeem Philadelphia’s reputation.”

Image uploaded by Centpacrr at English Wikipedia; transferred to Commons by Stevenliuyi using CommonHelper.

Fat Lotta Good…. “From its opening day on May 31,” Wikipedia recounts, “the exposition already faced challenges to its success. The fair opened with a heavy downpour of rain, causing many fair goers to leave. However, one man, Jacob J. Henderson had been proud to be the first person to enter the fairgrounds at the 9:00 A.M. opening. He stated that he had been to the Centennial with his parents, and did not want to miss opening day of the Sesqui.”

Kudos, Mr. Henderson.

“Within the first hour,” Wikipedia continued, “it is believed that less than 250 entered the gates of the fairgrounds. The fair drew a much smaller crowd than anticipated (about 10 million people). Variety dubbed it ‘America’s Greatest Flop’ [Ed: research U.S. Army’s 250th/Trump’s 79th…] at a loss of $20 million by August 1926. The exposition ended up unable to cover its debts and was placed into receivership in 1927, at which point its assets were sold at auction.”

A 1926 coin featured then-President Calvin Coolidge with George Washington. Image from Collectors Alliance via The New York Times.

Among its questionable historical attributes, see the tale of the infamous Washington/Coolidge half-dollar in “The Sublime, the Heartwarming, and (Lamentably) the Ridiculous Part 2.”

Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll focus on expos with which your author had some sort of vague connection/recollection. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025