Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

A PECAN CAPER

I AM BY BIRTH AN OHIOAN, sorta east of the Midwest and westward of true Easterners. This also dictates my way of speech. Indeed, I confess that as a kid I sang “Are Country, Tis of Thee….” until corrected by my radio work at Cleveland’s WBOE, our country’s first authorized educational station.

No; I’m not in this image from the Cleveland Metropolitan School District. But see also “Dialects That I’ve Heard, Like, Y’Know.”

This is not without relevance to todays’ tidbits, gleaned from Shelley Mitchell’s “How Pecans Went From Ignored Trees to a Holiday Staple—The 8,000-Year History of America’s Only Native Major Nut,” Nice News, November 26, 2025.

Pecan pie, part of our Thanksgiving celebration.

Shelley Mitchell writes, “Pecans, America’s only native major nut, have a storied history in the United States. Today, American trees produce hundreds of millions of pounds of pecans — 80% of the world’s pecan crop. Most of that crop stays here. Pecans are used to produce pecan milk, butter, and oil, but many of the nuts end up in pecan pies.”

Dr. Mitchell continues, “I’m an extension specialist in Oklahoma, a state consistently ranked fifth in pecan production, behind Georgia, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas. I’ll admit that I am not a fan of the taste of pecans, which leaves more for the squirrels, crows, and enthusiastic pecan lovers.”

We’re The Nuts; Pecans Aren’t, Kinda. “The pecan,” Mitchell recounts, “is a nut related to the hickory. Actually, though we call them nuts, pecans are actually a type of fruit called a drupe. Drupes have pits, like the peach and cherry.”

Wikipedia notes that other drupe-producing plants “include coffee, jujube, mango, olive, most palms (including açaí, date, sabal and oil palms), pistachio, white sapote, cashew, and all members of the genus Prunus, including the almond, apricot, cherry, damson, peach, nectarine, and plum.”

Above, immature pecan fruits. Image by SnickeringBear via Wikipedia. Below, Carya illinoinensis. Image from Muséume de Toulouse via Wikipedia.

You Say “ToMAYto and I say “ToMAHto.” Mitchell advises, “While you are sitting around the Thanksgiving table this year, you can discuss one of the biggest controversies in the pecan industry: Are they PEE-cans or puh-KAHNS?”

For whatever it’s worth, I’m a puh-KAHN kinda guy. Guessing from Shelley Mitchell’s Oklahoma residency, I’d conjecture she’s a PEE-can person.

Pecan Etymology. Mitchell describes, “The pecan derives its name from the Algonquin ‘pakani,’ which means ‘a nut too hard to crack by hand.’ Rich in fat and easy to transport, pecans traveled with Native Americans throughout what is now the southern United States. They were used for food, medicine and trade as early as 8,000 years ago.”

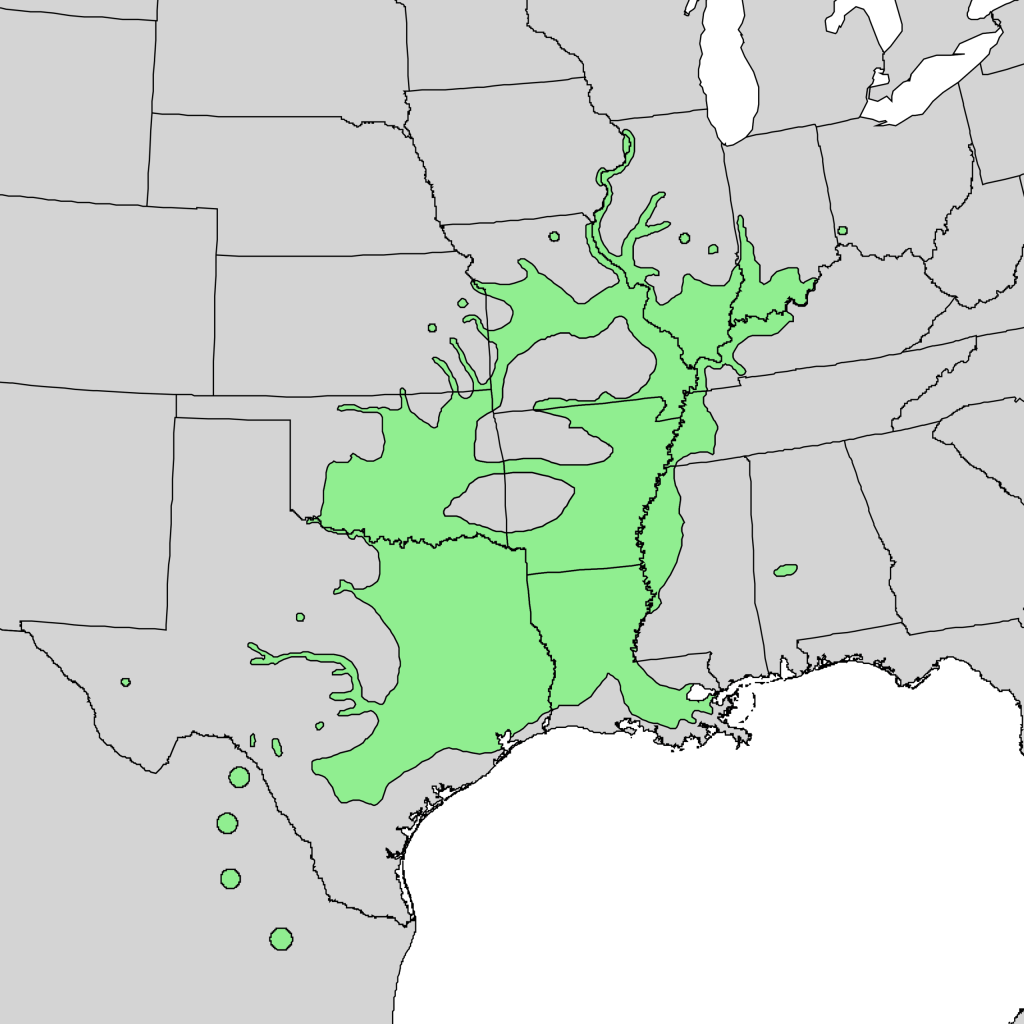

Image by Elbert L. Little, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, via Nice News.

And Guess Who Liked To Munch Them. Mitchell recounts, “Pecans are native to the southern United States, and while they had previously spread along travel and trade routes, the first documented purposeful planting of a pecan tree was in New York in 1722. Three years later, George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, had some planted pecans. Washington loved pecans, and Revolutionary War soldiers said he was constantly eating them.”

Competitive Growing. Pecan trees, Mitchell describes, “are alternate bearing: They will have a very large crop one year, followed by one or two very small crops. But because they naturally produced a harvest with no input from farmers, people did not need to actively cultivate them.”

“It wasn’t until the late 1800s,” Mitchell relates, “that people in the pecan’s native range realized the pecan’s potential worth for income and trade. Harvesting pecans became competitive, and young boys would climb onto precarious tree branches. One girl was lifted by a hot air balloon so she could beat on the upper branches of trees and let them fall to collectors below. Pecan poaching was a problem in natural groves on private property.”

A Pecan Protein Kick: Mitchell recounts, “During the Civil War and world wars, Americans consumed pecans in large quantities because they were a protein-packed alternative when meat was expensive and scarce. One ounce of pecans has the same amount of protein as 2 ounces of meat.” Several Apollo crews gained protein from easily stored pecans.

A 68-year-old pecan tree grown from seed at Morton Arboretum. Image by Bruce Martin via Wikipedia.

Shake ’Em for Their Own Good. Mitchell observes, “To keep pecan quality up and produce consistent annual harvests, today’s pecan growers shake the trees while the nuts are still growing, until about half of the pecans fall off. This reduces the number of nuts so that the tree can put more energy into fewer pecans, which leads to better quality. Shaking also evens out the yield, so that the alternate-bearing characteristic doesn’t create a boom-bust cycle.”

Let’s All Thank Antoine, an Enslaved Louisianan. Mitchell relates, “Grafting pecans became popular after an enslaved man named Antoine who lived on a Louisiana plantation successfully produced large pecans with tender shells by grafting, around 1846. His pecans became the first widely available improved pecan variety.”

“The variety,” Mitchell relates, “was named Centennial because it was introduced to the public 30 years later at the Philadelphia Centennial Expedition in 1876, alongside the telephone, Heinz ketchup and the right arm of the Statue of Liberty.”

Also exhibited were the Remington No. 1 typewriter, Hires Root Beer, and a Centennial Monorail. What to expect at next year’s Semiquincentennial? ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

This calls for a deep dive into pralines. And now I have this craving . . .