Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

OPERA AND COLONIALISM PART 1

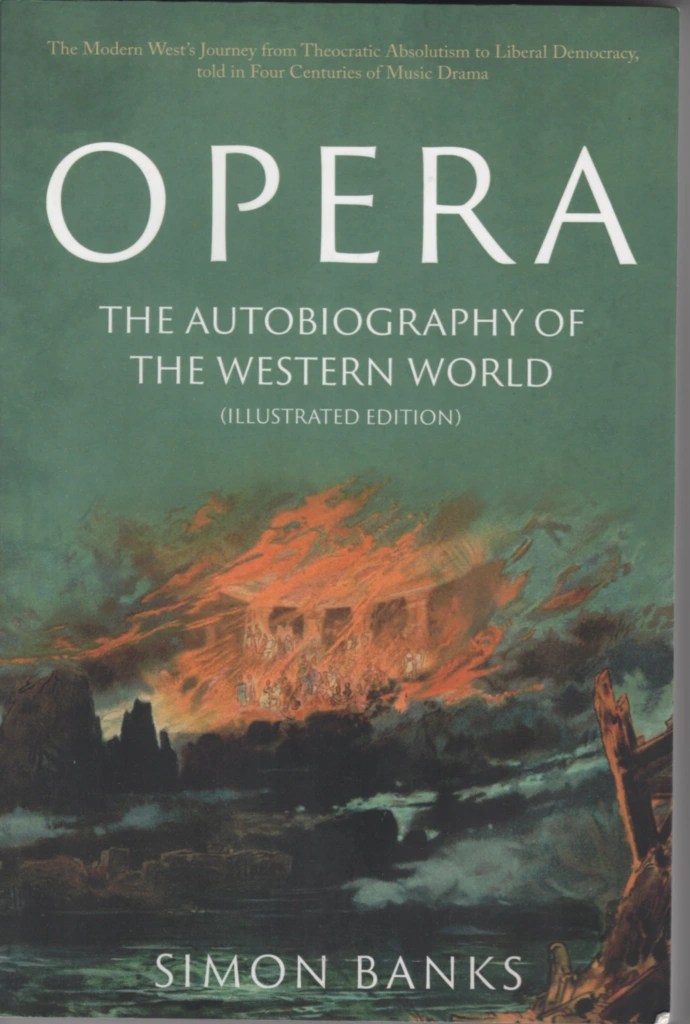

MY LATEST OPERA WITH OPERA NEWS contains “Terra (In)Cognita,” by Simon Banks. He “highlights shifting attitudes towards colonialism as reflected in opera across the centuries.” Surely an interesting topic. Indeed, Banks, who taught art history at the University of St. Andrews, has appeared at SimanaitisSays in “Hearing Ourselves in Opera” based on his book Opera: The Autobiography of the Western World.

Opera: The Autobiography of the Western World, by Simon Banks, Troubador Publishing, 2022.

Today and tomorrow in Parts 1 and 2, tidbits are gleaned from his “Terra (In)Cognita.”

Banks recounts, “For four of the five centuries since the advent of European colonialism, operas had been recreating and reimagining those momentous events, reprising them from widely contrasting ideological stances. A whole gamut of attitudes to exploration and conquest can be traced through several music dramas created between 1658 and 1992.” (This latter date chosen as the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s exploration of the Americas.)

1658, London. Competing for Territory in the New World. Banks describes, “The nations of western Europe were still fighting for land in the Americas when the masque The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru was performed in London. Four years earlier, in 1654, Oliver Cromwell—England’s Lord Protector—sponsored his own attempt at foreign conquest, an expedition to the Caribbean island Hispaniola.”

“Cromwell and the Puritans,” Banks observes, “had closed the London theatres on moral grounds. But this masque—a story of virtuous Incas and tyrannical Spaniards—was such a robust piece of anti-Catholic propaganda that Cromwell allowed the performances to go ahead. The music, now lost, was by Matthew Locke, and the text was by William Davenant, who claimed to be Shakespeare’s bastard son. In the final scene, gallant Protestant English adventurers rescue the Incas from the dastardly Spanish.”

Just the thing for Trump to assign to the Kennedy Center.

1733, Venice. The Cynicism of a City That Had Already Lost its Empire. “While the nations of the Atlantic seaboard had been creating new empires across the oceans,” Banks relates, “Venice had been losing a once-mighty, eastward-facing empire in the Mediterranean Sea. By the time the young Vivaldi was composing his oratorio Juditha Triumphans to celebrate a small Venetian victory over Ottoman forces at Corfu in 1716, only a few colonial outposts remained.”

In marked contrast to Cromwell’s propaganda 75 years before.

1755, Prussia. Voltaire and his friend Frederick the Great Condemn Colonialism. Banks describes Frederick the Great as “a ruler self-consciously enthused by the ideals of the Enlightenment.” In 1736, Frederick’s pal Voltaire wrote Alzire, ou les Américains. This was not just a rehash of “Spanish cruelty to the natives of Peru,” Banks describes, but “a robust attack on despotism.”

Vivaldi’s Motezuma, 17 years later, “would be told with ideologically driven, polemical bias,” Banks writes. “But there aren’t any heroes or villains in Vivaldi’s opera. The Venetians were too sophisticated to be partisan: They had seen it all before.”

An early edition of Voltaire’s Alzire. Image from Opera with Opera News.

Not to be outdone, Frederick wrote the libretto for the opera Montezuma (1755), “the noblest of noble savages,” Banks observes, “and a model of enlightened magnanimity.” Montezuma (“naively secure in his moral values”) sings, “We will show them our virtues—which may be unfamiliar to them./ The true statesmanship of the prince is based on justice and kindness…”

Then he’s tricked and killed by Cortés.

Tomorrow in Part 2, we encounter yet other perhaps mixed messages of colonialism. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025