Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

PLACE NAMES—SIGNPOSTS TO THE PAST

HISTORIAN MICHAEL WOOD WRITES, “… a rusting cast-iron signpost peeping through the foliage in a sunken lane gives me an inexplicable thrill. It’s the idea that the deep past might be still be touched, just around the corner.” This, from “Place Names Are Signposts to the Past. And How Revealing They Are,” BBC History, Vol 26 No 7 July 2025.

Illustration by Femke De Jong in BBC History.

Here are tidbits gleaned from his fascinating article, together with my own personal participation.

An Iron Age Village. “Take Ipplepen,” Professor Wood recounts, “a village with Roman and Iron Age roots in the hills near Torquay [a seaside town, some 220 miles southwest of London]. A recent dig here turned up a small post-Roman cemetery, in use till the eighth century, and a Roman butcher shop, with coins and broken amphorae that once held olive oil, wine, and fish sauce imported from the Mediterranean.”

Wood notes, “The name Ipplepen was first recorded in the 10th century, and contains a personal name that appears to be Roman-British or Celtic: Epilus or Ipela. In a region where the Celtic (pre-Welsh) language may have died out only after 1066, the name of a pre-English landowner was, incredibly, passed down.”

Rivers and Topography. “In the Home Counties [for us Yanks, typically Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, and Surrey; maybe Sussex],” Woods observes, “ancient British (or Welsh) place names are mainly gone—except for river names. Here they linger, from the Thames [Latin Tamesis, possibly from an ancient Celtic word meaning “dark water”] to smaller watercourses such as the wonderfully named Rib, Beane, and Maran (or Mimram) [these last two appearing in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 913] in Hertfordshire.”

“Sometimes,” Wood notes, “English newcomers didn’t understand these words. Avon, of course, has the same derivation as afon, Welsh for river. Bredon Hill includes no fewer than three words with the same meaning: bre is Welsh and dun is Old English, both translating as ‘hill.’ So: Hill-hill Hill!”

Indigenous People Pushed Out; Their Names Remain. Wood observes that “Place names show how the dominant language takes over in whichever way it happens. Across the world, the pattern is the same—especially in the age of imperialism. Think of the overlay of English names in Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, or the U.S.”

U.S. Examples. “There,” Wood continues, “the indigenous inhabitants were wiped out or pushed into corners, yet place names associated with them still populate the landscape, from Alabama to Wyoming [the first, a Muskogean-speaking tribe; the second, a double-whammy: a western territory named for the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania, its name from the Lenape Munsee xwéːwamənk, meaning ‘at the big river flat.’].

“Take Michigan,” Wood recounts, “which is ‘big lake’ in the speech of the Ottawa tribe; or Mississippi, ‘Big River” in Algonquin. From Malibu to the Napa Valley, telltale signposts remain, despite ethnic cleansing by European settlers and colonists.”

My Own Research. Being as I am a Born-Again Californian, I squirm a bit at ethnic cleansing of a more recent variety. As noted in Wikipedia, the name California is “most likely derived from the mythical island of California in the fictional story of Queen Calafia, as recorded in a 1510 work The Adventures of Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. Queen Calafia’s kingdom was said to be a remote land rich in gold and pearls, inhabited by beautiful dark-skinned women who wore gold armor and lived like Amazons, as well as griffins and other strange beasts.”

Queen Califia, from a 1937 mural by Lucile Lloyd, located at the California State Capitol.

I seem to recall once being taught etymology suggesting “hot furnace” from the Latin calida fornax, but modern scholars tend toward the literary origin. Or maybe De Montalvo knew his Latin?

And Napa? Wikipedia suggests, “The word ‘napa’ is of Native American derivation and has been variously translated as ‘grizzly bear,’ ‘house,’ ‘motherland,’ or ‘fish.’ Of the many explanations of the name’s origin, the most plausible seems to be that it is derived from the Patwin word napo, meaning ‘house.’ ”

Lots of Californian Spanish. Given that California belonged to Spain and then to Mexico before Frémont and his crowd came along, it’s completely logical that lots of its place names have Spanish origin: Costa Mesa, “Coastal Mesa,” the latter, “an isolated, flat-topped elevation.” Some of the apocryphal ones are closer to Spanglish: Agua del Mar (“water of the sea”).

And More Native Americans. I looked up Malibu: Wikipedia says, “The area is within the Ventureño Chumash territory, which extended from the San Joaquin Valley to San Luis Obispo to Malibu, as well as several islands off the southern coast of California. The Chumash called the settlement Humaliwo or ‘the surf sounds loudly.’ The city’s name derives from this, as the ‘Hu’ syllable is not stressed.”

Today, surfer dudes do likewise: Wikipedia says they call it “The ‘Bu.’ ”

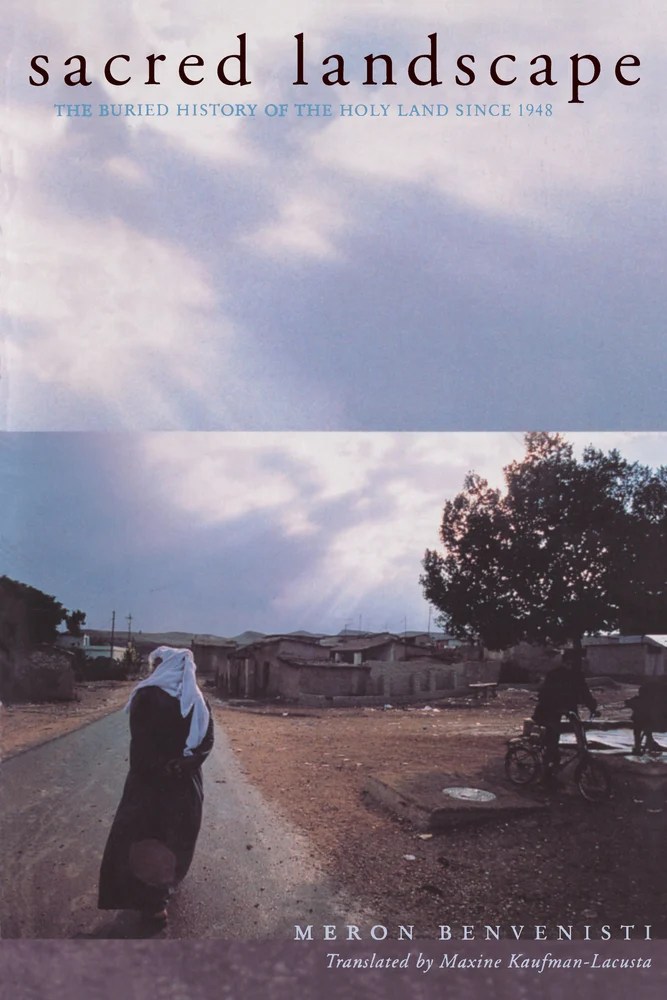

Sacred Landscape. Wood cites “a revealing example is told in Sacred Landscape 2002), a remarkable book by the Israeli writer, historian, and political scientist Meron Benvenisti. His father was an Israeli geographer on the Government Names Commission tasked after 1948 with giving Palestinian villages and landscapes names linked to Israel’s biblical homeland.”

Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948, by Meron Benvenisti, translated by Maxime Kaufman-Lacusta, University of California Press, 2002.

Wood continues, “New Hebrew place names, resonating with the biblical story of the Hold Land, replaced the Arabic names of more than 9000 natural features villages, and even ruins in the new Israel.”

Baedeker’s Palestine and Syria, 1912. Though its names are original, alas its sentiments tend toward the Eurocentric extreme.

Wood concludes, “The story Benvenisti tells is about the battle over the ‘signposts of memory’ that are essential to all human beings. As the novelist Milan Kundera said, ‘the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.’ Often slowly, imperceptibly over time—but sometimes at a stroke—history is erased.”

Wood stresses, “But sometimes it still magically endures, even over millennia. People have long memories. Ask the folk in Ipplepen.”

Or the Associated Press and many of us. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025