Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

F1 FUELS 1989–1991: HOW GREEN THEY WEREN’T PART 2

PART 1 BEGAN OUR CRIBBING OF YOUR AUTHOR’S PRESENTATION at the 2008 SAE Motorsports Conference. We pick up here in Part 2 with another hydrocarbon not included in F1 Rocket Fuels of 1989–1991.

Not Toluene Either. Contrary to a lot of internet traffic, another thing these fuels were not is toluene. This was a principal fuel component evolving in the turbo era, 1977-1988, the period immediately prior to the one we’re discussing. For information on this, I recommend two sources. Honda published, albeit in limited edition, “A Decade of Continuous Challenge: A Record of Honda’s Formula One Racing Activities,” ISBN 4-9900262-0-9. Ian Bamsey collected a lot of this information in his excellent “McLaren Honda Turbo: a Technical Appraisal,” ISBN 0854298401.

This and following images from “Three Retrospectives of Alternative Racing Fuels—They’ve Burned What??”

Briefly, here’s a look at toluene and several of its hydrocarbon siblings. Two things made it particularly attractive to the F1 crowd at the time: its Research Octane of 124 and its specific gravity of 0.867. Note, this was a no-refueling era and, for part of it, with turbos having a limited fuel capacity as well.

Honda notes that by 1988, the end of the turbo era, its cars were running a mixture of 84 percent toluene and 16 percent n-heptane, the blend calculated to yield an RON of 101.8. The regulation stated a maximum of 102 RON, and the idea was to give a cushion against selective evaporation screwing up any post-race octane check.

But Enough of Toluene. It wasn’t the Rocket Fuel of legend, if for no other reasons than its ubiquity, its notoriety and its membership in the hydrocarbon family.

Forget Hydrocarbons. That is, there’s good reason to believe the stuff, whatever it was, wasn’t a hydrocarbon. Indeed, there are technical papers suggesting as much.

In general, these papers describe a development process yielding higher-energy fuels. It’s suggested that di-olefins were examples of such high-energy compounds (and, indeed, later ruled illegal). In case you’d like to do some reverse engineering with other things prohibited, these include peroxides and nitroxides (ruled out in 1992) and “substances capable of exothermic reaction in the absence of external oxygen” (banned from 1993). I leave amplification of these points as an exercise for the better organic-chemically informed.

The papers note these high-energy fuels were characterized by their higher flame speed, lower octane quality, lower stoichiometric air/fuel ratio and increased density. The higher flame speed allowed an increase in bore-to-stroke ratio which in turn gave increased engine speed.

It’s also noted that physical and thermochemical properties of these could be predicted with high accuracy. “Computer modelling therefore became a key part of Formula 1 fuel development.” This modeling includes a Power Index, defined in terms of characteristics of a candidate fuel component.

The first term relates to the heat generated per unit mass of air; the second, to the increase in number of moles of gas due to combustion. The authors note, “Whilst there are many gross simplifications in this definition, it was found to be surprisingly accurate and it was therefore used as a first selection criterion for candidate fuel components.”

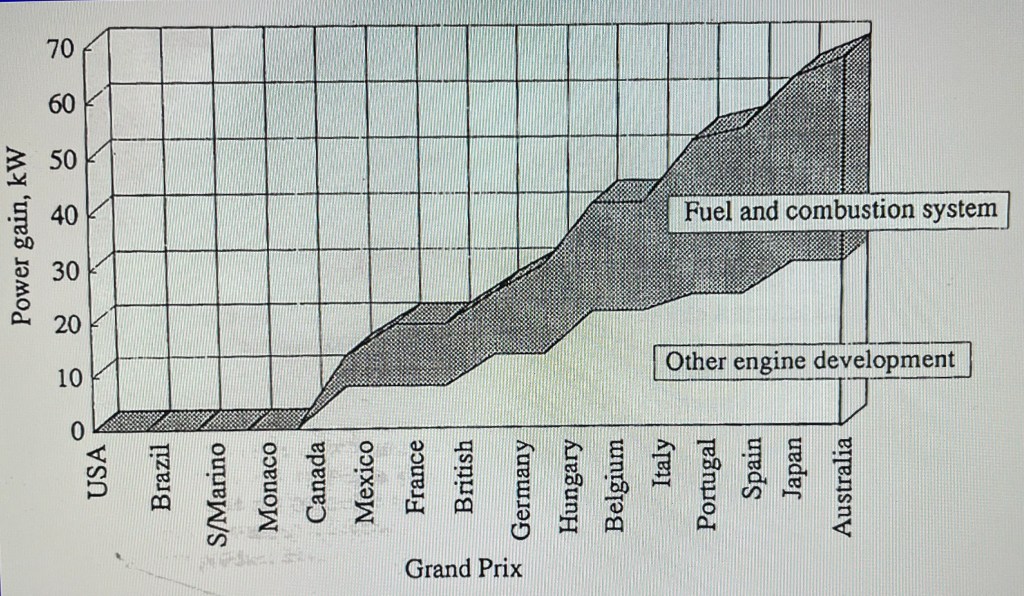

How well did this methodology work? During the 1991 season, the last of our Rocket-Fuel era, the McLaren Hondas gained 90 bhp, roughly half of this attributable to fuel and combustion technology.

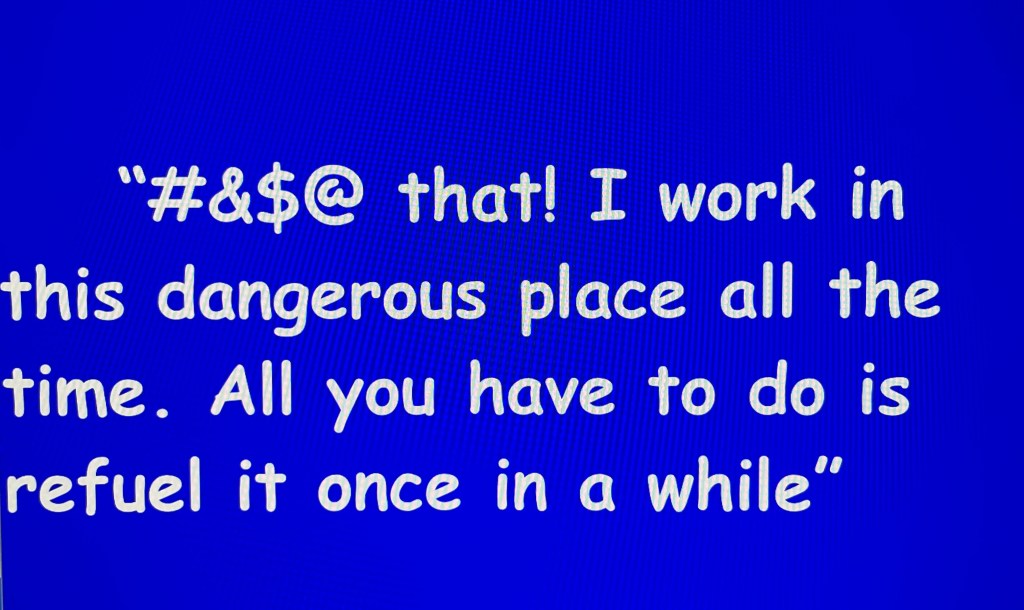

I close with some comments that cannot be attributed, but they’re certainly fun:

And on that wonderfully FIA-incorrect driver’s assessment, I bring my own comments to a close. Thanks for your kind attention. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Dennis, thanks very much for your F1 fuel analysis. Perhaps you can expand it to earlier days. Over the years I’ve watched a few pre-war Mercedes-Benz GP cars being fired up. One was Joel Finn’s at Lime Rock, back in the 1980s. His mechanic wore a full rubber apron, rubber gloves, rubber boots, and a face shield while carefully mixing the fuel then pouring it into the tank. It smelled just like shoe polish!

Thanks for your kind words. Actually this is an in-depth focus on part of an earlier piece, Formula 1 Fuel Tidbits, back in 2021. There, I shared Karl Ludvigsen’s information on Auto Union V-16 fuel back in the Thirties: 60% alcohol, 20% benzol, 10% diethyl ether, 8% gasoline, 1.5% toluol/nitrobenzol, and 0.5% ricinus oil.” Gad. No wonder the mechanic’s garb.