Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

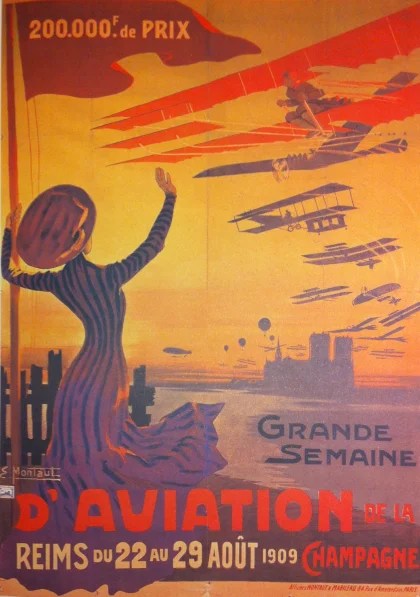

GRANDE SEMAINE D’AVIATION DE LA CHAMPAGNE, 1909

IT WAS LESS THAN SIX YEARS after the Wright Bros. first flew ever so tentatively at Kitty Hawk that the world celebrated heavier-than-air craft at the Grande Semaine d’Aviation de la Champagne near Rheims, France.

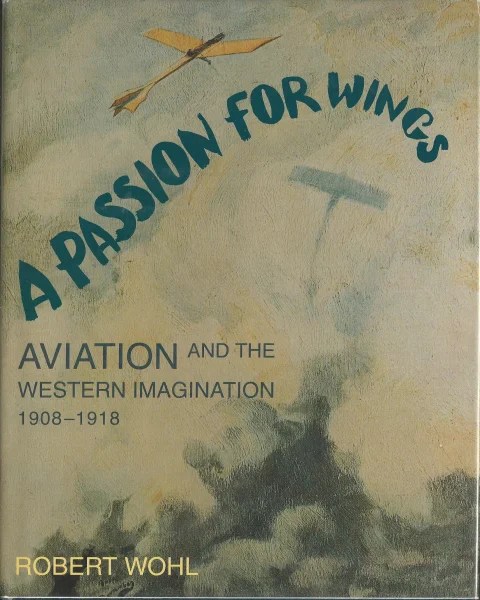

Robert Wohl described in A Passion for Wings: Aviation and the Western Imagination, “The Rheims meeting had been carefully organized by a group of investors gathered together under the name of the Compagnie Générale de l’Aérolocomotion…. The officers of the company no doubt felt encouraged by the fact that the Aéro-Club de France had agreed to lend its prestige to the event and to monitor the competitions.”

A Passion for Wings: Aviation and the Western Imagination, by Robert Wohl, Yale University Press, 1994.

“They could also take heart,” Wohl continued, “in the fact that the very grand Marquis (soon to be Prince) de Polignac had assumed the presidency of the committee. As the head of the house of Pommery, he was well placed to tap the resources of the major champagne producers of the Marne who contributed the lion’s share of the nearly 200,000 francs in prize money and the additional 225,0000 francs judged necessary for the preparation of the site. The combination seemed inevitable. Just as champagne was the quintessential French drink, so aviation seemed destined to become the typically French means of locomotion. Both embodied the qualities of the French “race”: élan, esprit, audace.”

Wohl noted “the fusion of champagne and the Wright Flyer against the background of Rheims cathedral.” This and following images from A Passion for Wings.

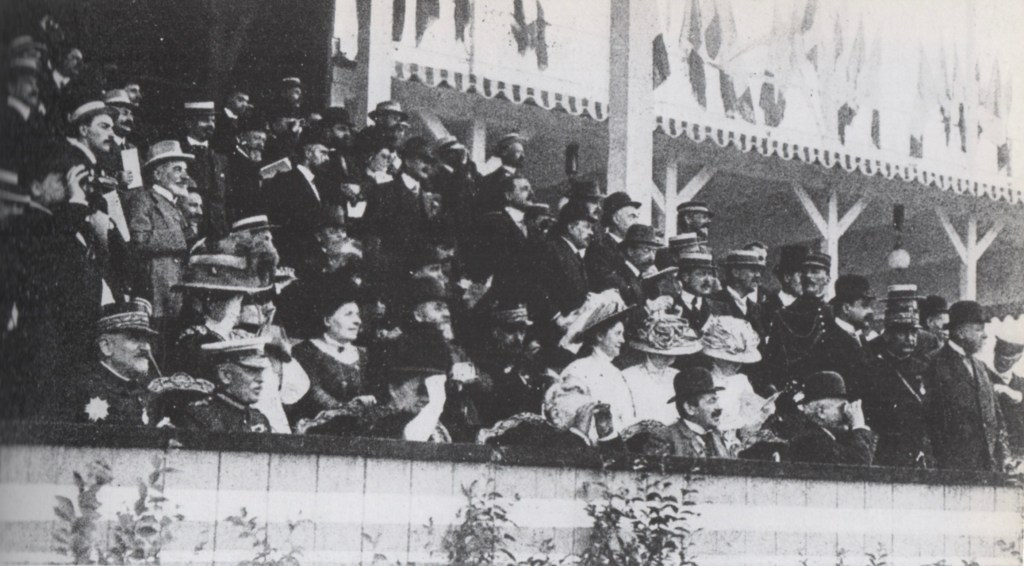

A Grand Setting at Bétheny. “The organizers of the meet,” Wohl observed, “had spared no expense to provide the spectators an experience with all the comforts and distractions of a world fair. A railroad track had been laid to transport the spectators from Rheims to Bétheny, and a station christened Fresnay-Aviation had been erected to receive them. Three hundred meters from the terminal, four grandstands, with elegantly outfitted boxes, had been built to accommodate three thousand people.”

Wohl continued, “A large and well-stocked buffet restaurant, decorated with festoons of electric lights in the form of pearls, was created to satisfy the appetites of those able to afford it. Bars dispensed the finest champagne. Fifty cooks and 150 waiters had been mobilized to prepare and serve les gens aisés over two thousand meals a day.”

A 10-Km Piste. Wikipedia describes, “A rectangular competition course of 10 km (6.2 mi) marked by four pylons was set up for the various competitions, with the strip intended for taking off and landing in front of the grandstands, opposite which was the timekeepers hut, provided with a signalling system to indicate to the spectators which event was being competed for.”

The Gordon Bennett Trophy. The week’s principal event was the first running of the Gordon Bennett Trophy, consisting here of two laps of the 10-km piste. Wohl recounted, “American Glenn Curtiss defeated Louis Blériot and won the Gordon Bennett Prize in a thrilling race to see who could cover twenty kilometers in the fastest time. Accelerating and then leaning into the turns like the motorcycle champion he was, Curtiss bettered Blériot’s time by 5.6 seconds and became the fastest man in the air as he already was on the ground. On the last day, he beat Blériot again over a course of thirty kilometers, reminding the French that despite the absence of the Wright brothers, they still had to take into account the Americans.”

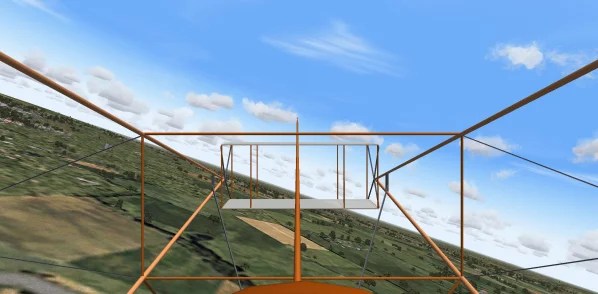

Above, my GMax rendering of Curtiss and his Rheims Racer; below, a view above the Bétheny-Aviation circuit.

The Grand Prix de Champagne. Henri Farman and his Farman III biplane won the week’s distance event with a flight of 189 km (110 mi). Wikipedia describes, “Farman eventually landed because the competition stopped at half-past seven, and any distance flown after this time did not count. On landing, in the words of the correspondent from the London Times, he was ‘seized upon by the enthusiastic crowd and carried in triumph to the buffet, where a scene of almost delirious excitement was witnessed.’ ”

Farman passing a pylon in his 180-km run. “Notice how low he is flying,” Wohl comments.

“Although French by upbringing,” Wikipedia notes, “Farman’s father was British and he was therefore also technically British, this mixed nationality being celebrated by a military band playing both the French and the British national anthems to celebrate his victory.”

Other Competitions. Curtiss’s Rheims Racer took the Grande Prix de la Vitesse for the quickest three laps at 69.82 km/hr (44.37 mph). Farman garnered the Prix des Passengers, the only pilot to complete a single lap with two passengers. Hubert Latham piloted his Antoinette VII to 155 m (509 ft) garnering the Prix de l’Altitude. Louis Blériot’s Type XII won the Prix du Tour de Piste, with the fastest single lap of 76.95 km/hr (47.8 mph). Only a month before, Blériot had flown his Type XI across La Manche/The English Channel.

There was also a Prix des Aéronats for lighter-than-air craft. Only two competed; five laps took 1 hr. 19 min. Quelle meh. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

C’est mignifique, mon Ami’s!

Marcie, Tom!