Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

FRANK MUIR ON EDUCATION AND LITERATURE PART 1

FRANK MUIR, HE OF MUIR AND NORDEN “My Word!/My Music!,” also put together a wonderful collection of things he enjoyed reading.

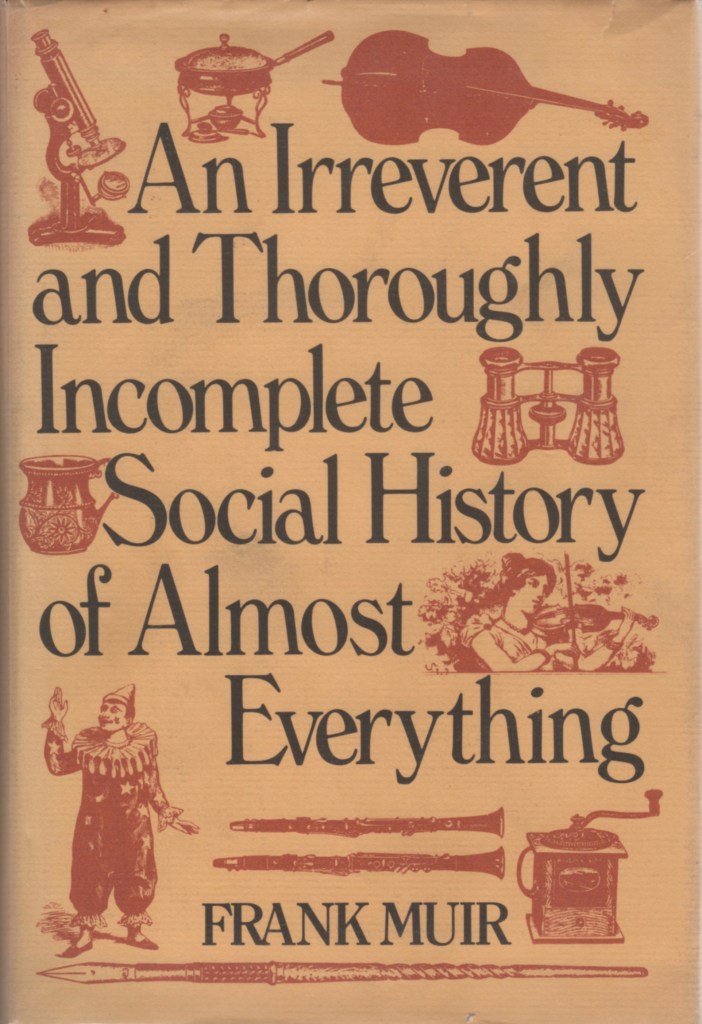

An Irreverent and Thoroughly Incomplete Social History of Almost Everything, by Frank Muir, Stein and Day, 1976.

In contrast to our country’s current slumping into anti-intellectualism, here in Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow are tidbits gleaned from Muir’s book, specifically on education and literature.

An Early Example: Horses Versus Children. Muir notes, “One of the reasons for the low standard of teaching was that it was poorly paid. The English governing class was more interested in the schooling of its horses than of its offspring:”

“It is pitie, that commonlie more care is had, yea and that emonges verie wise men, to finde out rather a cunnyng man [wise man, wizard, magician] for their horse than a cunnyng man for their children. They say nay in worde, but they do so in deede. For, to the one they will gladlie give a stipend of 200 Crounes by year, and loth to offer to the other 200 shillings.—Roger Ascham (1515–1568) The Schoolmaster.”

Mr. Russell on his Bay Hunter by James Seymour, c. 1740. Image from The Works of Chivalry.

An Oxford Education. Muir writes, “Oxford continued to be regarded as England’s pinnacle of learning; the standard against which others could be measured:”

“The clever men at Oxford/ Know all that there is to be knowed./ But they none of them know one half as much/ As intelligent Mr. Toad.—Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932) The Wind in the Willows.”

University of Oxford. Image from ox.ac.uk.

And Its Result. Muir comments, “Socially, it was accepted as the finishing-school for upper-class young men:”

“I was a modest, good-humoured boy. It was Oxford that has made me insufferable.”—Max Beerbohm (1872–1956) Going Back to School.”

Beerbohm, Self-caricature, 1897. Image from the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection via Wikipedia.

On Modern Languages. Muir recounts, “Another subject which came to be taught regularly in public schools was Modern Languages:”

“Life is too short to learn German.”—Thomas Love Peacock (1785–1866).”

“It is good to be on your guard against an Englishman who speaks French perfectly; he is very likely to be a card-sharper or an attaché in the diplomatic service.”—W. Somerset Maugham (1874–1966).”

On Mathematics. Muir notes that “Mathematics was more widely taught:”

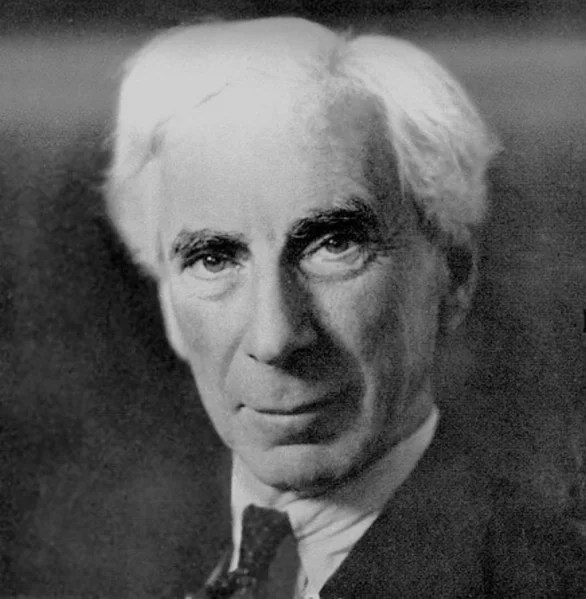

“Mathematics may be defined as the subject in which we never know what we are talking about, nor whether what we are saying is true.—Bertrand Russell (1872–1969). Mysticism and Logic.”

Bertrand Russell, 1872–1970, English philosopher, writer, mathematician, social critic, political activist, Nobel Laureate in Literature, 1950. Photo from 1938.

“That arithmetic is the basest of all mental activities is proved by the fact that it is the only one that can be accomplished by a machine.—Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860).”

Gee, I wonder what Schopenhauer would have thought of A.I.?

Tomorrow in Part 2, we share cogent views of George Bernard Shaw, William Faulkner, Samuel Johnson, and others; even the author of SimanaitisSays. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

I harken back to my Junior year of an Aerophysics curriculum when my calculus prof suggested that I’d enjoy taking “Number Theory” as one of my electives. First session involved a mind bending argument how 1 was not equal to 1, but then proceeded to claim that +1 and -1 were equivalent but not of equal value.Then and there, I decided my future was in Engineering, not Mathematics, and scurried to the drop/add office!