Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

ORSON WELLES ON DIRECTING PART 2

YESTERDAY, PART 1 SET THE STAGE for Orson Welles sharing his views on directing. Here in Part 2, he shares some history, more than a few opinions, and many insights about his multifaceted career.

The Director—A Relatively Recent Occupation. “Actors,” Welles observes, “have been directing themselves for 2000 years…. The director of the theatre is an invention about 150 years old, maybe 200 maximum. It was always the chief actor with the assistance of the stage manager who put on the play. Nowadays, I think largely inspired by the cinema, there is a new giant walking across the planet who’s called the conductor or director…. But the cinema and the theater must not depend on the director.”

The Story Paramount? “People always answer that by saying, ‘Yes, it’s the story, the script,’ Welles says. “They are absolutely wrong!”

“The story, the script is the third most important thing. You can make a wonderful film about nothing. Look at Fellini.”

Ouch.

“The most important thing in a movie,” Welles says, “is the acting and everything which is in front of the camera.”

The Director’s Role? Welles tells the French film-school students, “And the decadence of the cinema, and we have decadence, comes from the glorification of the director as not the servant of the actor but as the master.”

So much for the auteur theory? Not really.

Welles’ First Film Director Stint. Welles describes, “The first day I directed a film was the first day I had ever been on a movie set. I was illuminated by the grace of total ignorance. And I was surrounded by my friends who had been with me in the theater for years.”

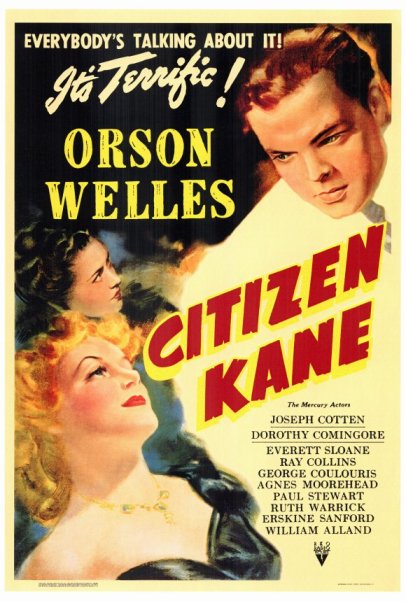

This, of course, was Citizen Kane; Welles was 25.

“I believed it was the job of the director to arrange the lights,” he says. “So for the first ten days I arranged the lights. And after ten days, somebody [likely Gregg Toland] took me aside and said ‘That’s usually the work of the cameraman.’ So I apologized to him and he said ‘the reason I wanted to work with you is that you’ve never made a movie and your ignorance would teach me something.’ And he said it did.”

Welles continues, “I should really stop for a year and learn. ‘No, you’ll only need about three hours,’ I was told.”

And indeed, there’s a wonderfully entertaining book, The Orson Welles Crash Course in Cinematography, Taught by Gregg Toland ASC, by David Worth: “A WILDLY Fictional Account of: How the Very Young Theater & Radio Sensation Orson Welles Learned Everything About The Art of Cinematography in Half an Hour… Or: Was It a Weekend?”

A Nuanced View on Directing. “I think directing,” Welles says, “is the most overrated job in the world. It’s the only one I really love in show business, but I think it is tremendously overrated.”

Welles summarizes, “The only job that a director can do in a film of real value is to do something more than what will happen automatically….”

If a director is “completely a cameraman, completely a writer, completely an actor, then his contribution is a real one,” Welles claims. “Otherwise he’s simply the man that says ‘Action,’ ‘Cut,’ ‘Take it a little slower,’ ‘Take it a little faster,’ and nobody will ever discover that he doesn’t know anything.”

Advice to Film-School Students. “So,” Welles says, “since I’m not talking to actors, let us respect and love them, cherish them, help them to be great because they make the cinema unforgettable.”

Excellent food for cinematic thought. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Welles makes good points while defending directing, so long as it’s his. As years went by, he increasingly tripped over his own ego, which diminished his movie.

If a director akin to a conductor, is that not a necessary role? Consider how some of the latter rush through, for example, Ravel’s La Valse and other symphonic works, losing sweep, nuance, charm.

A detached bystander often the best to render an overview.