Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

WHICH WAY IS NORTH? AND WHY ANYWAY? PART 2

YESTERDAY IN PART 1, WE BEGAN SHARING James Vincent’s London Review of Books assessment of Jerry Brotton’s Four Points of the Compass: The Unexpected History of Direction. Here in Part 2, ecclesiastical architecture enters the discussion and so do Polaris and the digital blue dot “You.”

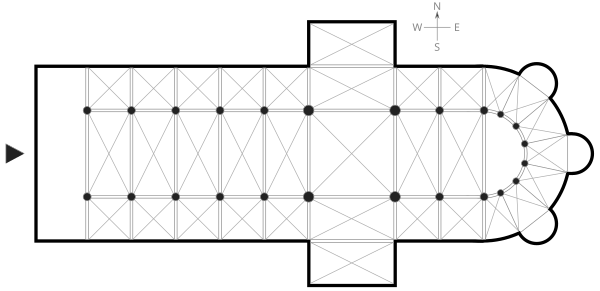

Architectural Controversies. Vincent describes, “Early Christian churches were built so that the altar, congregation and priest faced ad orientem (literally, towards sunrise), a decision that was eventually a focus of theological controversy.”

An early Christian church plan. Image from Wikipedia.

“During the Reformation,” Vincent recounts, “the Church of England placed altars in the north of the church or had the priest stand at the north end of the communion table instead of facing east.”

Recent episodes of “Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light” suggest Henry VIII’s serial matrimony bringing him into conflicts with Pope Clement VII.

A Long-Standing Squabble. Much later Vincent relates, “In the 19th century, the Oxford Movement began to worship ad orientem once more as part of a broader effort to reclaim the Catholic heritage of Anglicanism. The issue even reached Parliament, Brotton notes, when ad orientem services were banned by the Public Worship Regulation Act of 1874 along with other elements derided as ‘ritualism.’ (The Act was repealed in 1965.)”

Most recently, Vincent notes, “As Pope Benedict XVI wrote in 2000, ‘praying towards the east is a tradition that goes back to the beginning. Moreover, it is a fundamental expression of the Christian synthesis of cosmos and history.’ ”

How Come North is Up? “Given the power of the east-west axis,” Vincent says, “it may seem surprising that the eastward orientation of the world was ever displaced, yet it was, on maps at least. Brotton identifies a number of reasons north became primus inter pares of the four cardinal directions. It starts with Greco-Roman culture, in particular the cartography of the Alexandrian scholar Ptolemy, who knew the world was a globe and thought the best way to project it was as a grid. On such a map, the vertical lines of longitude converge naturally at two poles (the choice to put north on top seems to have been purely a matter of custom).”

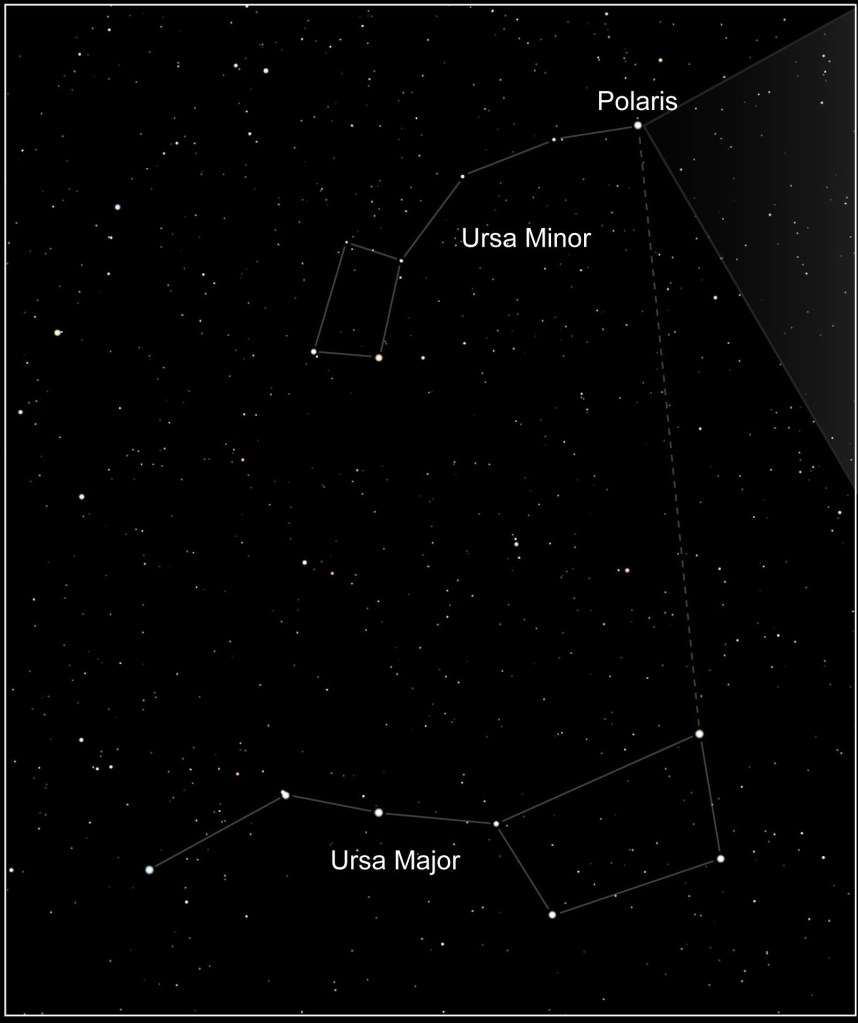

Polaris: the Ship-Star. Vincent continues, “In the northern hemisphere, Polaris, the North Star, also aided navigation before compasses. For Anglo-Saxon navigators, Polaris was known as the scip-steorra, or ship-star, and became associated with the Virgin Mary in her role as mankind’s guide in the journey towards Christ – she was Stella Maris, ‘Star of the Sea’. As the compass became crucial for trade, warfare and exploration, these antecedents led pilots and mapmakers to privilege north over south, and this orientation was cemented from the medieval period onwards by European colonisation and global trade.”

Polaris, the North Star. Image from NASA/HST via Wikipedia.

Today’s Digital World and “You.” Vincent posits, “Do the dense layers of meaning associated with each cardinal direction persist in the modern age? Brotton ends his survey by noting the year the reign of the compass finally expired: 2008, which saw the launch of the iPhone and the creation of the blue dot, the constant marker in map apps by which we now orient ourselves.”

Well, here You are. Image formed with the help of Google Maps.

“ ‘In this our digitised century,’ Brotton writes, ‘there are now five directions – north, south, east, west, and the online blue dot: “You.” ’ ”

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Related

2 comments on “WHICH WAY IS NORTH? AND WHY ANYWAY? PART 2”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Information

This entry was posted on May 1, 2025 by simanaitissays in I Usta be an Editor Y'Know and tagged "Behold the Pole Star" James Vincent "London Review of Books" (review of Brotton's "Four Points of the Compass", "Google Map" London Review of Books "You" blue dot, "Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light", Brotton digitized world: north/south/east/west/blue dot "You", Polaris (the North Star) navigation heightened its popularity, Squabble in Church of England facing east or north? (the latter Henry VIII doings).Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-jw0Categories

Recent Posts

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

Ah, but the Blue Dot is placed on a map that is oriented, by default, with North at the top…

I’m surprised that the MAGATs haven’t demanded that the Blue dot be replaced by a Red one!