Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

GEDANKENEXPERIMENTE TO EN ZED

HERE’S A WONDERFUL “THOUGHT EXPERIMENT,” albeit utterly impossible in the real world: tunneling through the center of Earth to the other side. BBC Sounds offers “What Would Happen If We Fell Straight Through the Earth?” And to emphasize our trip being strictly a GedankenExperimente BBC also provides “Three Minutes to the Centre of the Earth.” Here are tidbits gleaned from both of these fascinating broadcasts, together with other Internet sleuthing.

The Earth’s Crust. Dr. Paula Koellemeijer, Associate Professor of Geophysics & Royal Society URF, University of Oxford, describes, “Our world is made of layers, a bit like an onion.”

This and following images from Dr. Koellemeijer’s BBC piece. The crust is about 35 km [22 m.] thick and a mere 1 percent of the Earth’s mass. This and other caption information from “What Would You See On a Journey to the Centre of the Earth,” by David Whitehouse, New Humanist, June 17, 2015.

“And as far as we know,” Dr. Koellemeijer continues, “life as we know it exists only in the first layer, the crust. In the crust, you’ll find the burrows of animals such as moles and badgers. The deepest is made by Nile crocodiles and can reach depths of 12 meters [39 ft] .”

“The crust,” Dr. Koellemejir says, “is also home to ancient underground cities like Elengubu in Turkey, an elaborate labyrinth capable of housing 20,000 people.”

For more details, see Geena Truman’s “Turkey’s Underground City of 20,000 People,” BBC, August 11, 2022.

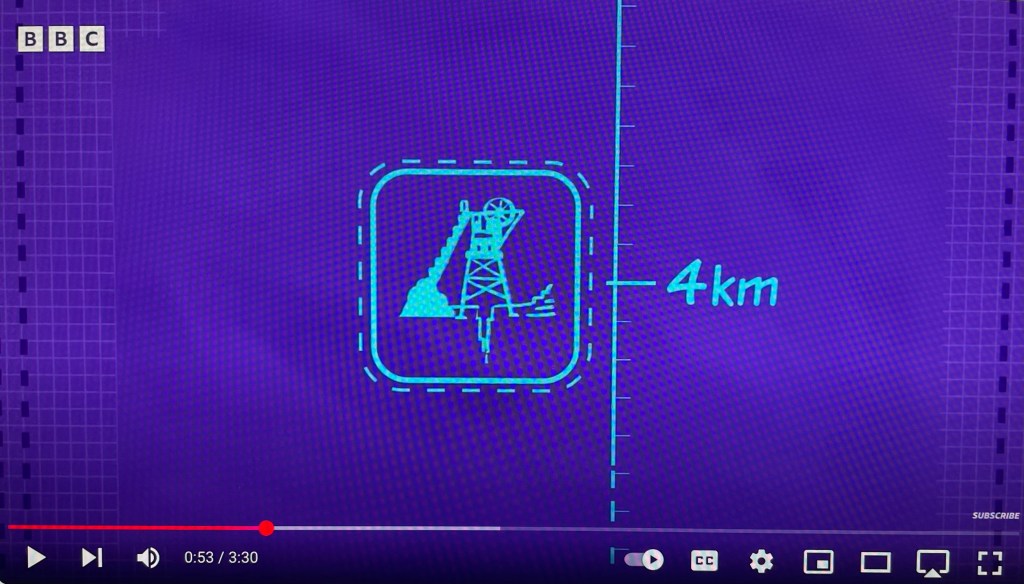

“The world’s deepest mine,” Dr. Koellemeijer recounts, “can go down to around 4 kilometers [2.5 m.].”

“Then there’s the deepest hole ever drilled,” she notes, “the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia. Some call it the gateway to hell with locals claiming to hear the screams of tortured souls.”

The Earth’s Mantle. “At around 30 to 50 km [18.6 to 31 m.] down,” Dr. Koellemeijer says, “we reach the mantle, made of hot rock which appears solid to us but actually floats very slowly, just a few centimeters a year.”

The mantle, consisting mainly of oxygen, silicon, magnesium, and iron, comprises about 82 percent of the Earth’s volume and 65 percent of its mass.

“These delicate shifts,” she notes, “can give rise to earthquakes above.”

The bottom of the mantle is reached at 2900 km [1802 m.] There, two giant blobs the size of continents cradle the next layer, the outer core.

For more on these blobs, see Tuzo and Jason at the New Humanist article.

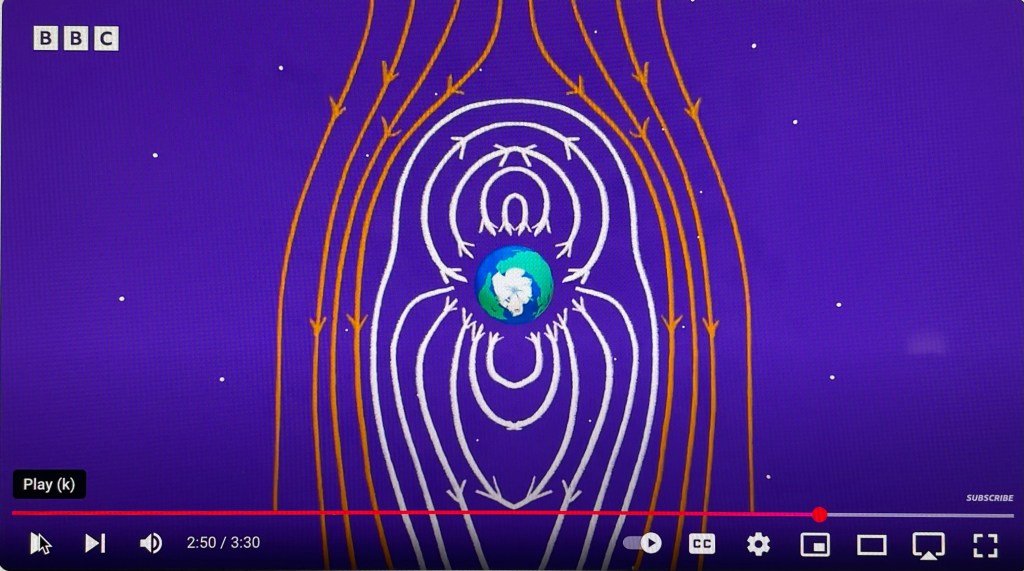

The Outer Core. “There is an ocean of sorts,” Dr. Koellemeijer recounts, “but this one consists of flowing red hot iron and nickel with its own currents and jet streams.”

The outer core, occupying around 10 percent of the Earth’s volume and 27 percent of its mass, is about the size of the planet Mars.

“This motion creates a magnetic field that protects the Earth from dangerous solar rays,” notes Dr. Koellemeijer.

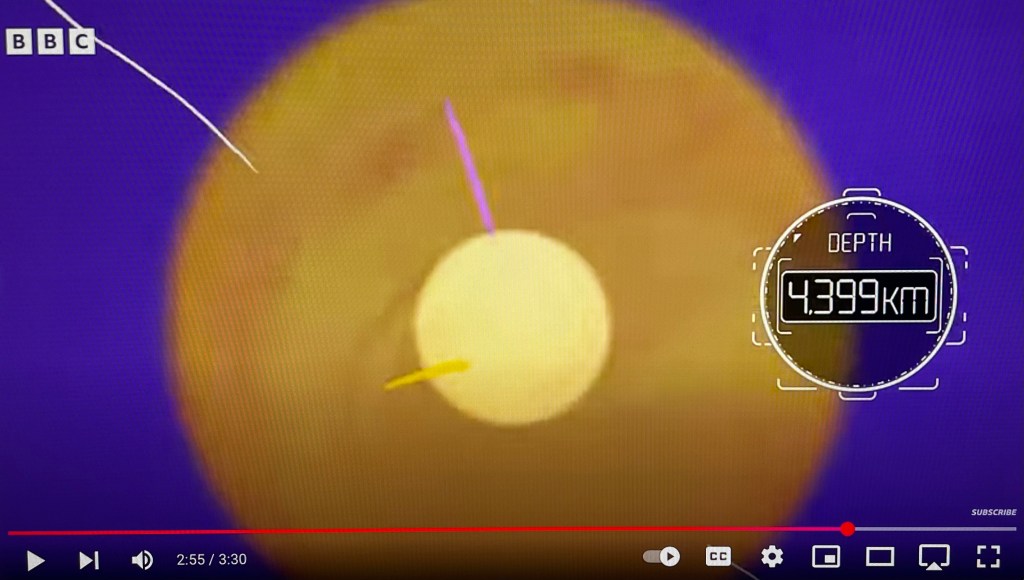

The Inner Core. “The final layer,” she describes, “is known as the inner core. It’s 6000 degrees in here. The pressure is so intense that the metals have crystalized forming a solid sphere at the centre of our planet.”

The inner core’s iron and nickel comprise only a half percent of Earth’s volume, but because of their super density nearly 2 percent of its mass.

Our Trip From London to New Zealand. Richard Easther is a physics professor at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He describes our GedankenExperimente tunneling from London to Auckland.

First, let’s imagine that our imaginary tunnel is devoid of air. Otherwise, the gravitational force would encounter air resistance both on the way to the center and back up to the surface.

No problem; this is after all a thought trip.

But the Earth Rotates. Second, Professor Easther suggests, “This would work a lot better on a planet that didn’t spin. If you standing on the surface of the Earth, you’re moving at the better part of 1000 km/h [621 mph]. So you’d keep that speed as you fall into the hole. But the middle part of the pipe is rotating much more slowly and you’d actually finding you bump into the wall of the tunnel.” Instead, he assumes you ride on rails or the like.

Gravity Does Its Job. “When you get to the centre,” Professor Easther recounts, “you’d be falling at the better part of 20,000 km/h [12,427 mph], gravity having been able to do its job and carrying you through the other side.”

“And if you didn’t have to worry about the heat at the centre and there was no air in the pipe,” the professor observes, “you’d arrive at the top [sorta the bottom] of the pipe at no speed.”

“If someone grabbed you,” Professor Easther says, “you’d be able to get out and have a fun day in Auckland. And if someone didn’t grab you, then you’d fall back to where you started from.”

How long would the trip take.? The “Gravity train” entry at Wikipedia recounts, assuming Earth were a perfect sphere of uniform density, London to Auckland (or vice versa) would take 2530.30 seconds (nearly 42.2 minutes). And don’t forget setting up the ankle grab on arrival. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025

Fascinating ove— underview. Perhaps Russia’s Kola Superdeep Borehole would be a fine place for our Felon-in-Chief. Muskrat might want to accompany him.

Nice post 🕺🎸