Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

GRIMM TALES

NO TYPO HERE. THE BROTHERS GRIMM: A BIOGRAPHY is a book by Ann Schmiesing given a review by Colin Burrow “Ogres Are Cool,” London Review of Books, March 20, 2025. Here are tidbits gleaned from this, rare among book reviews with its occasionally humorous comments.

The Brothers Grimm: A Biography, by Ann Schmiesing, Yale University Press, 2024.

The Brothers Grimm and Napoleon. Burrow describes, “Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, born in the mid-1780s, were the older children of a district magistrate in Steinau in the German state of Hesse. They grew up with close links to the government of this small, rural, but relatively prosperous state. The Grimms saw Hesse invaded by Napoleon in 1806. It was then absorbed into the kingdom of Westphalia, which was ruled by Jérôme Bonaparte, the emperor’s self-indulgent youngest brother, and was intended to become a constitutional model for other German states under French rule.”

Hmm…. Where have I heard this before? Think “Bernstein’s (and Voltaire’s) Candide.” But do you remember Vichy France? (see “Casablanca Lore” and “I Wish I Said That (First).”

Wilhelm Grimm, 1786–1859, (left) and Jacob Grimm, 1785–1863. Portrait by Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, 1855, via Wikipedia.

Jacob the Scholar. “The Grimms,” Burrow writes, “were not the conjoined and identical twins of the popular imagination. Jacob was the elder and the more scholarly of the two. He held a number of positions as a librarian, first to Bonaparte (whose inclinations were not bookish), then in the library at Kassel, and later in the University of Göttingen, where he was also a professor. Like many librarians before and since, he tried to minimise the time he wasted in meeting the unreasonable demands of readers to get access to the books in his charge. Indeed his career could be seen as a great vindication of the general grumpiness of librarians….”

Grimm’s Law. “Jacob’s German Grammar,” Burrow observes, “set out principles of linguistic change that came to be given the forbidding name of ‘Grimm’s Law.’ It explains the way consonants evolved between proto-Indo-European and early Germanic languages, and was one of the foundations of both comparative linguistics and the systematic study of etymology. Jacob was, even as scholars and philologists go, at the dusty end of the academic spectrum, but his nose was not always shoved up his own vowels.”

Burrow explains, “He, along with his brother Wilhelm, was one of seven people who lost their jobs at Göttingen after protesting against the suspension of the constitution by the new king of Hanover, Ernst August, in 1837.”

Imagine such things happening today.

Wilhelm the Rewrite Man. Burrow notes, “Wilhelm was the more outgoing and complex of the two. He eventually married Henriette Dorothea Wild, the daughter of a pharmacist whose family supplied many of the tales that made the Brothers Grimm famous. After the first edition of the Children’s and Household Tales in 1812 it was Wilhelm who did most of the rewriting and extending.”

Burrow says, “The first edition was not child-friendly or popular. It had learned notes and included a more than usually savage story about how children learn to chop up other children. This was omitted from later editions, though the tales that remained were ruthless enough: wicked stepmothers are shod in red-hot shoes or imprisoned in spiked barrels, while Cinderella’s sisters cut off their toes in order to fit into her slipper and end up getting their eyes pecked out by doves.”

Don’t you love it being doves, the aviary symbols of peace?

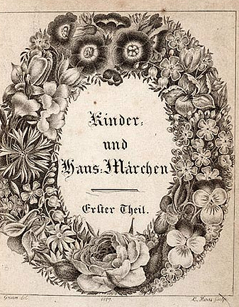

Title page of first volume of Grimms’ Kinder und Hausmärchen, (1819) 2nd edition via Wikipedia.

Moralism and Adjectives. Wilhelm, Burrow observes, “certainly added charm, detail, some honks of obtrusive moralism and a scattering of adjectives.”

“Old Marie.” Burrow recounts, “Wilhelm marked some tales in his copy as deriving from ‘Marie,’ and his son incorrectly supposed that this was a family servant known as ‘Old Marie.’ The actual Marie wasn’t very old and certainly wasn’t a peasant who muttered tales while she stirred the cabbage soup. She was the daughter of a government official called Johannes Hassenpflug and her brother Ludwig married the Grimms’ sister, Charlotte.”

You know how family stories get muddled.

Grimm Politics. Burrow writes, “Ann Schmiesing’s very thorough biography shows the way the activities of the Grimms as both philologists and folklorists (and medievalists too) grew from a wider network of German Romantic nationalists.… The political ideal that underpinned their work was of a Germany united through a common tongue, which should be governed (in the Grimms’ preferred model) not by French invaders but by a constitutional monarch who loved the German language and (ideally) German philologists. This ideal was, needless to say, never realised during or after their lifetime.”

Burrow continues, “Schmiesing carefully distinguishes the Grimms’ ideal of a ‘Volk’ united by a common language from later aggressive forms of German nationalism…. The Grimms were not Nazis, but it’s not hard to see why the Nazis loved the Grimms.”

What a grim observation. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025