Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

1811: A VERY GOOD YEAR

ALAS, AAAA SCIENCE NOTES, “When it comes to understanding the medieval climate of Europe, scientists face a daunting issue: Europeans loved to chop down their oldest and biggest trees.”

“Outside of northern Scandinavia and high mountain ranges,” Paul Voosen writes in Science, July 19, 2024, “this penchant for felling trees has made it difficult for researchers to obtain records of tree rings, a standard paleoclimate tool, leaving gaps where most Europeans actually lived.”

Ah, but those Europeans liked to drink wine too. And, as Voosen recounts, “Medieval Wine Testing Fills In Gaps About Europe’s Climate.” Here are tidbits from this Science article, together with my usual Internet sleuthing.

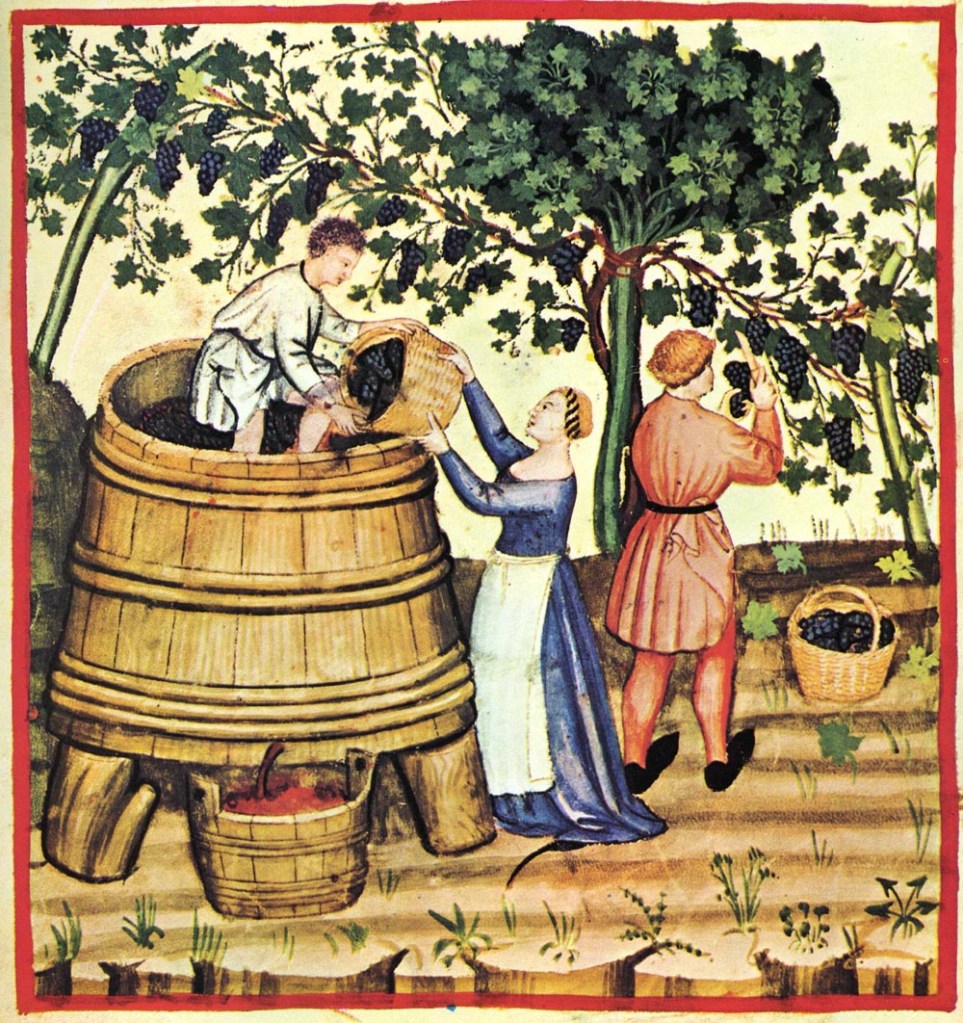

“The first wine press was probably the human foot and the use of manual treading of grapes is a tradition that has lasted for thousands of years and is still used in some wine regions today.” Caption and Public Domain image from Wikipedia.

Past Temperatures and Sweetness. Voosen writes, “Records of grape harvests found in the cellars and monasteries of Europe stretch back to the 1400s and can provide a powerful resource for teasing out past temperatures. ‘Compared with the average tree ring, it’s really excellent,’ says Stefan Brönnimann, a paleoclimate scientist at the University of Bern. ‘I’m totally surprised how well it works.’ ”

“Several years ago,” Voosen continues, “Brönnimann and co-authors showed that the date of grape harvests was an excellent indicator of past temperature in the growing season. Now, in a new study published last month in Climate of the Past, they’ve shown that another measure—the reported sweetness of grape juice before fermentation—can also chart temperatures.”

Image from copernicus.org.

A Classic Chronicle; a Fine Year. “For many years, Christian Pfister, a climate historian at Bern, has explored wine records, recorded in tomes like Karl Pfaff’s Württemberg Wine Chronicle. After grapes were harvested and crushed, the resulting juice, or ‘wine must,’ would be sampled by local experts, who rated its sugar content on a five-point scale. The more sugar, the more alcohol would end up in the wine.”

Image from Macy’s Wine Shop.

“And,” Voosen notes, “it’s long been known that high temperatures boost a grape’s sugar content. Hot years led to popular wines on the market, such as 1811’s Comet Wine, named after the Great Comet that lingered in the sky for 260 days.”

Screening Out Other Effects. The researchers looked at sugar ratings from ten locations across France, Germany, Switzerland, and Luxembourg. Historical events that might have prevented optimal harvest such as war, famine, or disease were screened out.

Nevertheless, Voorsen writes, “Some mysteries appeared in the data. The 1470s, for example, had the highest rated wine must of all time, suggesting Europe went through a warm spell even as it was entering a centuries-long cool period known as the Little Ice Age. ‘But we don’t really know what happened then,’ Brönnimann says. To try to find out, the team has begun feeding wine records into a new paleoclimate model, released this year, that attempts to simulate global conditions on a month-by-month basis from the 1400s onward.”

Another Approach: Wine Tax Records. Lea Schneider is a paleoclimatologist at Justus Liebig University Giessen. Voorsen recounts that she “is part of a team using wine tax documents to look at the response to climate extremes. In a preprint released last week, the team found records showing three straight years of low production, after a known volcanic eruption injected particles into the atmosphere that would have cooled Europe. ‘That is much stronger than what we would have expected,’ she says. Tree rings from the Alps do not show such a strong cooling imprint from the eruption. ‘We’re still not fully sure how to explain it.’ ”

Today’s Climate Change. “Starting around the late 1980s,” Voorsen notes, “ratings of sugar content began to rise steeply, to the point where the record resembles the famed ‘hockey stick’ spike in global temperature records. The overlapping trends aren’t guaranteed to continue: Studies suggest excessive drought and frequent heat waves could eventually kill off vineyards, especially in southern Europe. But for now, global warming has been good for European wine harvests, Brönnimann says. ‘From 2003, it’s been just good years.’ ”

And don’t forget that 1811 comet. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

It’s getting hard to find a good, low-alcohol white wine (as many German wines once were) any more. Especially from California. Even the Rieslings are pushing 12-13%, and the old standard 12-13% reds are closing in on 15%. Those “special” yeasts from UC Davis are now needed to ferment some red wines mostly dry (at near-Port alcohol %), given the sugar in the grapes. Of course, the studies and modeling have been done showing that California will become too hot for any high-quality (indeed, essentially any) grape-growing over the next 20-40 years. Has adaptation started in Europe yet, with plantings of warm-weather varieties farther north? England now has quite a few vineyards, and even Ireland has some.