Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

THE CASE OF THE KERNLESS “f” AND MISFIT “?”

SOME BOOK REVIEWS ARE JUST AS MUCH as I want to know. Others, like Gill Partington’s “Every Watermark and Stain,” London Review of Books, June 20, 2024, encourage me to read the entire book.

What a great tale. Joseph Hone writes about the bibliographic skullduggery of Thomas James Wise, a lowly clerk whose ambitions transformed him into president of the Bibliographical Society of London. Only, as reviewer Partington notes, “As his reputation grew, he was able to play both gamekeeper and poacher…. He was no longer simply a collector of ‘modern first editions’: now he was manufacturing them too.”

Here are tidbits recounting “how this ‘Moriarty of the book world’ met his match in a duo of intrepid young book dealers, John Carter and Graham Pollard.”

The Book Forger: The True Story of a Literary Crime that Fooled the World, by Joseph Hone, Chatto, 2024.

The Culprit. Partington describes “Wise’s life of crime began innocuously enough in the 1870s, amid the bluestockings and genteel eccentrics of Bloomsbury’s literary societies. He was an obsessive bibliophile, spending every spare moment rummaging through second-hand book-barrows. He sold his rarer finds at a profit to finance his collecting habit, but the most valuable treasures remained far out of his reach.”

Thomas James Wise, 1859–1937, British bibliophile/thief, who collected the Ashley Library, now housed by the British Library, and later became known for the literary forgeries he printed and sold.

Wise’s M.O. Partington continues, “Working by day for the Rubeck trading company, Wise had risen from junior clerk to broker in exotic goods. Books, he recognised, were just another sort of commodity. He was quick to spot gaps in the market, exploiting the tantalising ‘what-ifs’ in publishing history.”

Wise would concoct a tale of a “what-if,” and then forge a work to fill that gap.

As an example, Partington offers, “In 1896 he published Literary Anecdotes of the 19th Century, in which he speculated that Algernon Swinburne’s ‘The Devil’s Due,’ a prose text published in the Examiner twenty years earlier, may also have been printed in pamphlet form for private distribution. Lo and behold, a few months later, Wise himself discovered just such a volume.”

How convenient.

The Bibliosleuths. Partington describes, “Carter and Pollard began their investigation in the early 1930s, homing in on one particular feature of Wise’s pamphlet edition: its ‘kernless f’. In older typefaces the character has an overhanging arm—a kern—which projects over its neighbours. The detail was phased out in the later 19th century as too fragile for machine presses.”

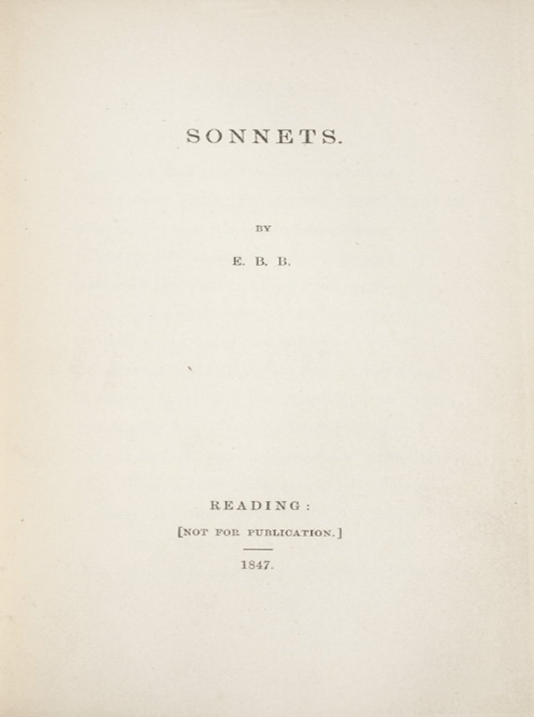

However, one of Wise’s early scams had been Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets by E.B.B., conjured out of an alleged sheaf of works slyly slipped into her husband Robert Browning’s pocket and later printed in a very limited 1847 edition.

Image from the University of Oregon: Unbound.

The Case of the Kernless “f” and Misfit “?”. Partington describes, “The ‘f’ of the Sonnets thus gave it away: there was no way it could have been published as early as 1847. Weeks of trawling through type specimen books then produced a match with a particular typeface: Long Primer No. 20, dating from 1883. Many printers used it, but there was another telling quirk in the Sonnets: the question mark seemed to be a misfit, an italic character used in place of the correct symbol. Like a fingerprint, it made the font unique.”

The scam unravels: “But the breakthrough didn’t come until Pollard spotted an 1893 facsimile edition of Matthew Arnold’s Alaric at Rome. The text displayed both the kernless f and the misfit question mark. Pollard only had to flip to the book’s front matter to see who had set the type: Richard Clay and Sons. But there was another important piece of information there too: the facsimile had been commissioned by Thomas James Wise.”

“In 1934,” Partington recounts, “Pollard and Carter published their exposé of the affair, An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets, printed, in a nice touch of irony, by Clay and Sons. Wise lapsed into silence, and an announcement in the TLS from his wife finally stated that ill-health prevented him from carrying on further ‘public correspondence’ about the matter. His death came just three years after Pollard and Carter’s book was published. He never confessed.”

Today, Partington notes, “ ‘Wiseana’ has become collectable in its own right—valuable precisely because it is the authentic work of a master forger.” Yet, Partington also observes, “Even the mahogany bookshelves housing his prized Ashley Library, dismantled after his death, turned out to be veneer.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

Related

Information

This entry was posted on June 17, 2024 by simanaitissays in I Usta be an Editor Y'Know and tagged "Every Watermark and Stain" Gill Partington "London Review of Books" review of Hone's "The Book Forger", "Sonnets" forgery discovered by kernless "f" and misfit "?", "The Book Forger: The True Story of a Literary Crime that Fooled the World" Joseph Hone, Carter and Pollard caught Thomas Wise bibliographic forgeries, Elizabeth Barrett Browning "Sonnets by E.B.B." forgery, Thomas Wise would ask "what if" and then provide forged answer.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-hVuCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012