Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

SHILLING FOR PROFESSOR EAGLETON

NOT THAT TERRY EAGLETON, English literary theorist and public intellectual, needs the like of me to encourage folks to his lectures. But his “Where Does Culture Come From?,” London Review of Books, April 25, 2024, is a thoughtful piece well worth recommending to others.

Indeed, for less literary types there’s even a YouTube of his presentation, delivered as the third of this year’s LRB Winter Lectures.

What follows here are tidbits gleaned from his LRB piece (honest, I learned of the YouTube only after having enjoyed the magazine version). His writing prompted me to some extracurricular Internet sleuthing as well.

C.V. Professor Eagleton served as Thomas Warton Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford (1992–2001) and John Edward Professor of Cultural Theory at the University of Manchester (2001–2008), together with visiting appointments at Cornell, Duke, Iowa, Melbourne, Trinity College Dublin, and Yale. Currently he’s Distinguished Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University.

Terrence Francis Eagleton, Salford, England-born 1943, English literary theorist, critic, and public intellectual. Image by Billion at English Wikipedia.

Public Intellectuals. Wikipedia describes public intellectuals as “impartial critics who can ‘rise above the partial preoccupation of one’s own profession—and engage with the global issues of truth, judgment, and taste of the time.’ ” This certainly fits Professor Eagleton.

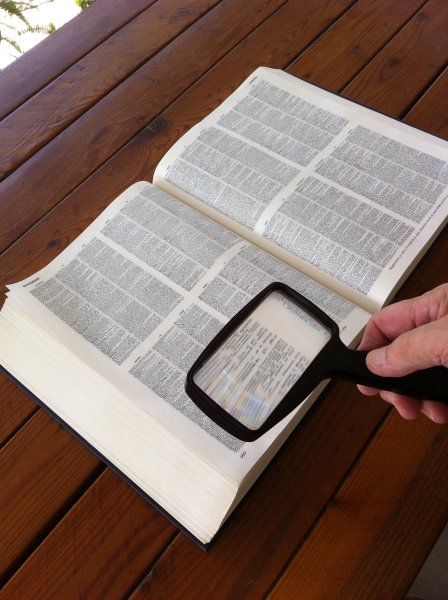

Culture Etymology: Here I turn to The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 1971, which devotes a full column of its microprinted page to Culture, “from Old French couture, cultura cultivation, tending, in Christian authors worship, see Cult.”

Eagleton cites that “a cognate word, coulter, means the blade of a plough. The kinship between culture and agriculture was brought home to me some years ago when I was driving with the dean of arts of a state university in the US past farms blooming with luxuriant crops. ‘Might get a couple of professorships out of that,’ the dean remarked.”

An Oedipal Child. “This is not the way culture generally likes to see itself,” Eagleton observes. “Like the Oedipal child, it tends to disavow its lowly parentage and fantasise that it sprang from its own loins, self-generating and self-fashioning.”

Eagleton continues, “Thought, for idealist philosophers, is self-dependent. You can’t nip behind it to something more fundamental, since that itself would have to be captured in a thought. Geist goes all the way down.”

Profiting from Economic Surplus. Eagleton notes, “You can’t have culture in the sense of galleries and museums and publishing houses unless society has evolved to the point where it can produce an economic surplus. Only then can some people be released from the business of keeping the tribe alive in order to constitute a caste of priests, bards, DJs, hermeneuticists, bassoon players, LRB interns, gaffers on film sets and the like.”

I like Eagleton’s examples of cultural types.

“In fact,” Eagleton says, “you might define culture as a surplus over strict need. We need to eat, but we don’t need to eat at the Ivy. We need clothes in cold climates, but they don’t have to be designed by Stella McCartney.”

The Middle Class. “If you open a history book at random,” Eagleton advises, “it will say three things about the period you light on: it was essentially an age of transition; it was a period of rapid change; and the middle classes went on rising. That’s the reason God put the middle classes on earth: to rise like the sun, but, unlike the sun, without ever setting.”

Wikipedia lists Eagleton’s ideological leanings as Continental philosophy and Marxism, these two broadly defined these days.

Marxism. Eagleton recounts, “Marx’s thought concerns the material conditions that would make life for its own sake possible for whole societies, one such condition being the shortening of the working day. Marxism is about leisure, not labour.”

“The only good reason for being a socialist,” Eagleton says (with a smile) “apart from annoying people you don’t like, is that you don’t like to work. For Oscar Wilde, who was closer in this respect to Marx than to Morris, communism was the condition in which we would lie around all day in various interesting postures of jouissance, dressed in loose crimson garments, reciting Homer to one another and sipping absinthe. And that was just the working day.”

Image from YouTube.

As noted in a preface to the YouTube presentation, “The word ‘culture’ now drags the term ‘wars’ in its wake, but this is too narrow an approach to a concept with a much more capacious history. In the closing LRB Winter Lecture for 2024, Terry Eagleton examines various aspects of that history—culture and power, culture and ethics, culture and critique, culture and ideology—in an attempt to broaden the argument and understand where we are now.”

And he does so in a cogent, articulate, and often amusing manner. Indeed, he’s the kind of professor I would have enjoyed. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

Related

3 comments on “SHILLING FOR PROFESSOR EAGLETON”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Information

This entry was posted on May 9, 2024 by simanaitissays in And Furthermore... and tagged "Where Does Culture Come From" "YouTube", "Where Does Culture Come From?" Professor Terry Eagleton "London Review of Books", culture profits from economic surplus (some folks have time for it), culture: an Oedipal child (sprang from its own loins), Eagleton on Socialism: "apart from annoying people you don't like", London Review of Books" LRB Winter Lectures 2024, Oscar Wilde on communism (per Eagleton): lie around all day reciting Homer and sipping absinthe".Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-hISCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

Culture “….tends to disavow its lowly parentage and fantasise that it sprang from its own loins, self-generating and self-fashioning.”

And any history book ” will say it was essentially an age of transition; it was a period of rapid change…”

Hilarious, because both so true. How wonderful that Dean Simanaitis culls such novel professors as above for us to sample.

Hi, Mike,

Agreed about Eagleton wit. As noted, I particularly liked his sampling of the cultured.

Thanks for the deanship. Ha. Of course, it’s Emeritus, Honorary, and Absurdum.

But your new honorarium is well earned, all the same. And am sure many SimanaitisSays followers would mightily agree.