Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

CELEBRATING LATE-19TH-CENTURY LITERARY ART

“THE VOGUE FOR LITERARY POSTERS,” Leah Greenblatt writes in The New York Times, April 5, 2024, “burned briefly, beginning in 1893 and lasting not much more than a decade.”

And what a decade! Greenblatt continues, “But the body of work it produced often hewed closer to fine art than advertisement, and slyly captured the zeitgeist of the times.”

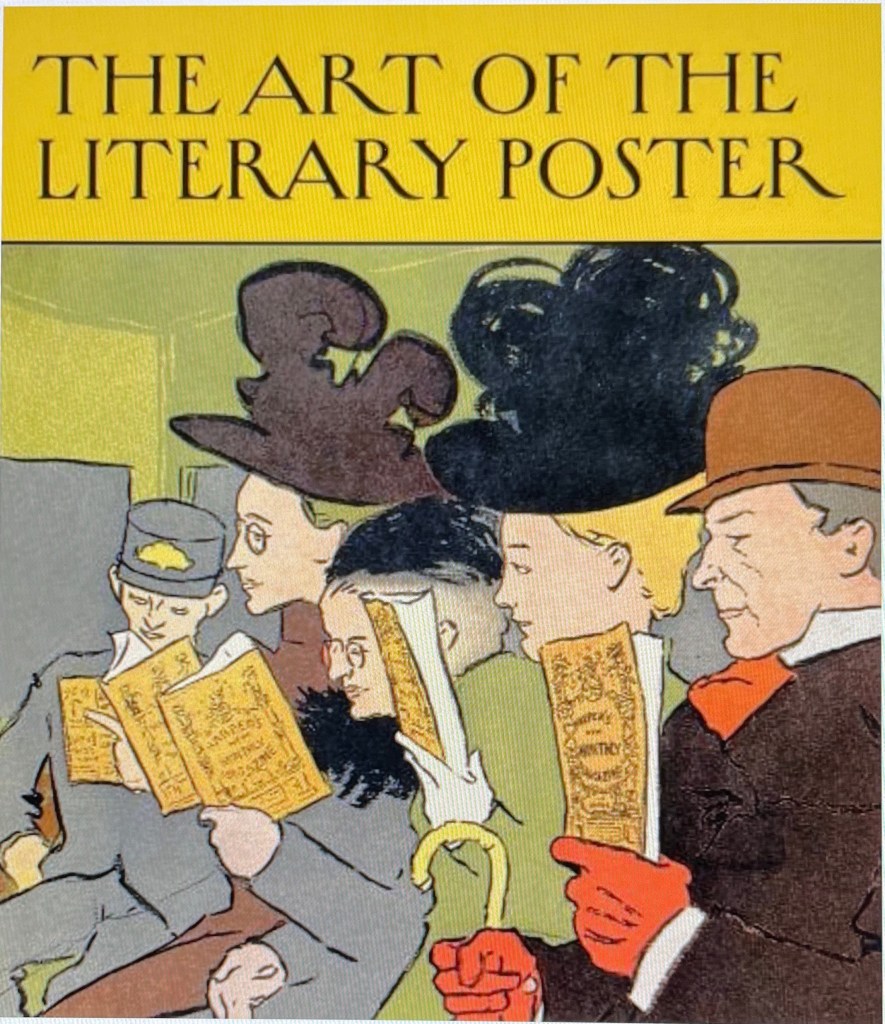

Here are tidbits gleaned from her review of The Art of the Literary Poster and from its IndieBound listing.

The Art of the Literary Poster, by Allison Rudnick, preface by Leonard A. Lauder, contributions by Jennifer A Greenhill, Rachel Mustalish, and Shannon Vittoria; The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2024.

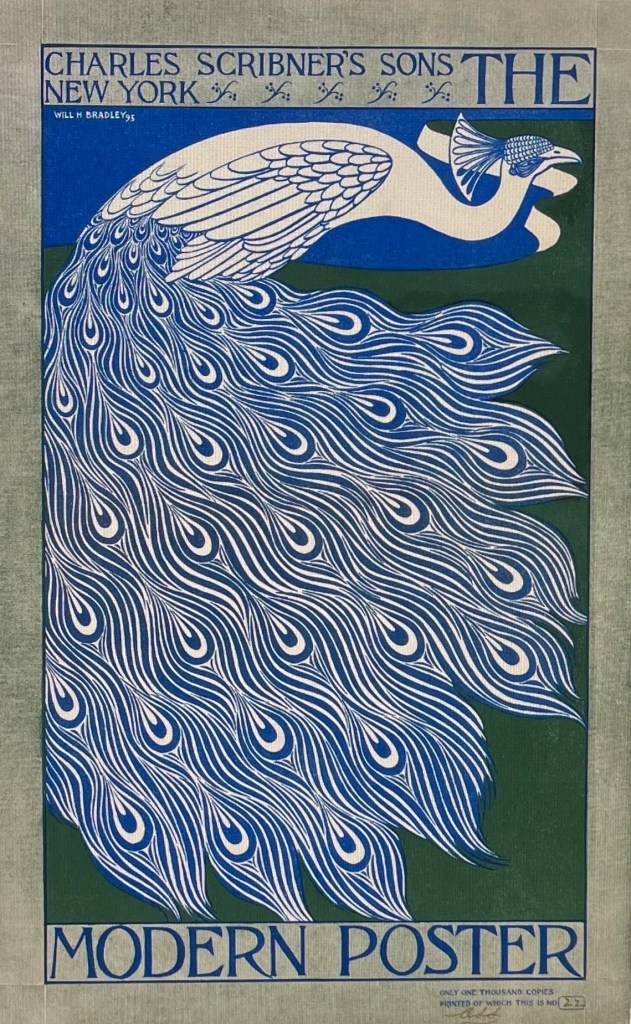

IndieBound writes, “Spurred by innovations in printing technology, the modern poster emerged in the 1890s as a popular form of visual culture in the United States. Created by some of the best-known illustrators and graphic designers of the period—including Will H. Bradley, Florence Lundborg, Edward Penfield, and Ethel Reed—these advertisements for books and high-tone periodicals such as Harper’s and Lippincott’s went beyond the realm of commercial art, incorporating bold, stylized imagery and striking typography.”

The book, IndieBound notes, is based on the renowned Leonard A. Lauder Collection.

Bearings. This ad emphasized the nexus of fitness and intellectualism in the late 1800s. Bearings was a cycling magazine.

Charles Arthur Cox, 1896. This and the following images from The New York Times, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Leonard A. Lauder Collection of American Posters, Gifts of Leonard A. Lauder.

In today’s context, I can’t help but mentally replace the magazines in their hands with smart phones.

Product Placement. A more direct product placement, this stylish cyclist artfully displays her favorite magazine.

Joseph J. Gould Jr., 1896.

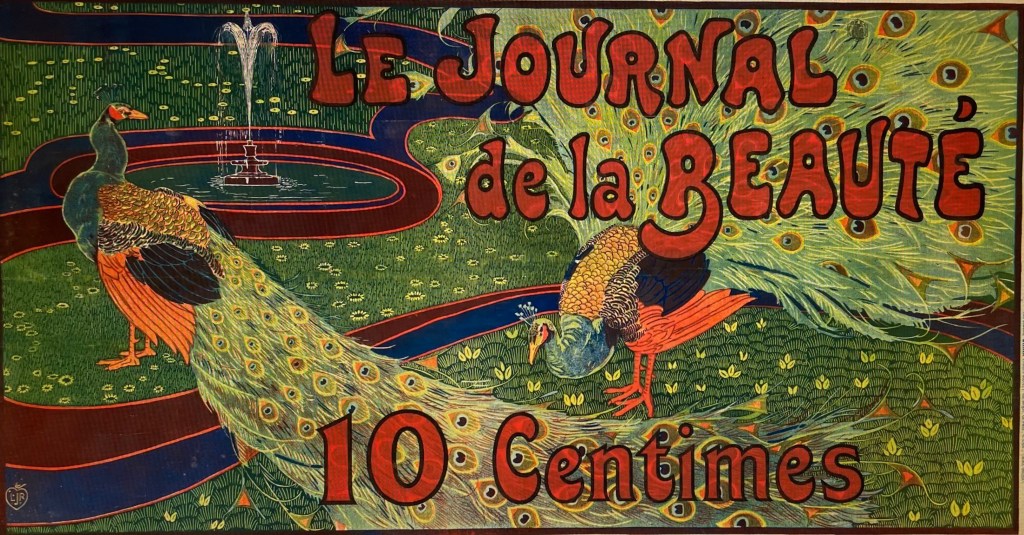

The Opulence of Peacocks. The Fin de Siecle (no cycling pun intended) was an opulent era. I particularly like the lushness of these peacocks from Le Journal de la Beauté.

Above, according to my Baedeker’s Northern France, 1894, 10 centimes was only 2¢ U.S., quite a bargain. Below, this lush bird is identified as the work of Will H. Bradley, 1895.

The New York Times, Sunday, Feb. 9. I thought I’d have a good puzzle in identifying which year of the era had a February 9 on a Sunday. A clue in the upper right suggests 1895, but no, artist Edward Penfield must have completed the artwork in advance. February 9, 1996, was a Sunday.

One of the articles cited has a followup here at SimanaitisSays. See “Wha’Cha’Call’It in Old Manhattan?”

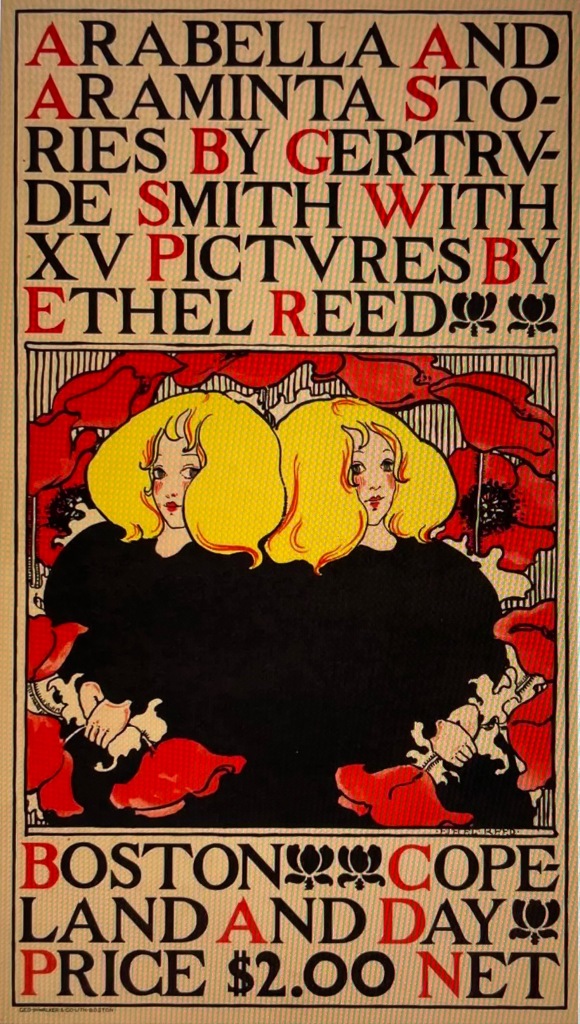

Two Sweethearts. I am fascinated to learn more about the two blondes in the Copeland and Day ad.

Arabella and Araminta illustration by Ethel Reed, 1895.

IndieBound lists the book today as “selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it.” The reprint costs $29.95. The online CPI Inflation Calculator (which goes back only to 1913) sets $2 of that year worth $63.74 now.

To me, the two young ladies are sweethearts at whatever the price. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

Related

One comment on “CELEBRATING LATE-19TH-CENTURY LITERARY ART”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Information

This entry was posted on April 12, 2024 by simanaitissays in I Usta be an Editor Y'Know and tagged "Arabella and Araminta" 1895 illos by Ethel Reed, "Bearings For Sale Here" Charles Arthur Cox 1896 (cyclists reading magazines), "Le Journal de la Beauté" peacocks, "Lippincott's Lady Cyclist with magazine" Joseph J. Gould Jr. 1896, "Scribner's ad peacock", "The Art of the Literary Poster" Rudnick (reviewed by Leah Greenblatt "The New York Times", "The New York Times" ad for Sunday Feb 9 (Jumel reference), Leonard A. Lauder Collection (late 19th-century literary posters).Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-hASCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

I received an email that you had shared a file with me on OneDrive. Legit or scam?