Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

POM’S ANALYSIS OF THE 1951 FERRARI 4 1/2-LITRE GRAND PRIX CAR PART 1

IMAGINE A SEGMENT OF FORMULA 1: DRIVE TO SURVIVE opening with commentary “Ehue! fugaces, Postume, Postume, Labuntur Anni.…”

Image from Netflx.

Thanks, Google Translate: “Alas! fleeting, posthumous, posthumous, the years slip away.” And there’s also Wikipedia to identify its source: The Odes by Horace, specifically, Book II 14 in which rich friend Postumus is warned of the inevitability of decay and demise.

By the way, my initial encounter wasn’t Horace’s Odes. It was Laurence Pomeroy’s Foreward to The Grand Prix Car Volume Two.

The Grand Prix Car Volume Two, by Laurence Pomeroy, F.R.S.A., M.S.A.E., Motor Racing Publications, 1954.

Pom writes, “But it is more profitable to evaluate the present in relation to the past and this is the task that I have set myself in this second volume of the Second Edition of The Grand Prix Car.”

I follow Pom’s suggestion here by gleaning tidbits about the 1951 Ferrari 4 1/2-Litre Grand Prix car. Indeed, I had sufficient fun doing so that there are Parts 1 and 2 today and tomorrow.

Post-war Grands Prix. A World Championship was initiated in 1950, engine displacements limited to 1.5 liters with forced induction or 4.5 liters with normal aspiration. Supercharged Alfa Romeos, essentially pre-war designs, were successful at first. Then along came the normally aspirated Ferrari 4 1/2-Litre. See “Alfa Romeo Versus Ferrari—The 1951 Grand Prix Season” here at SimanaitisSays.

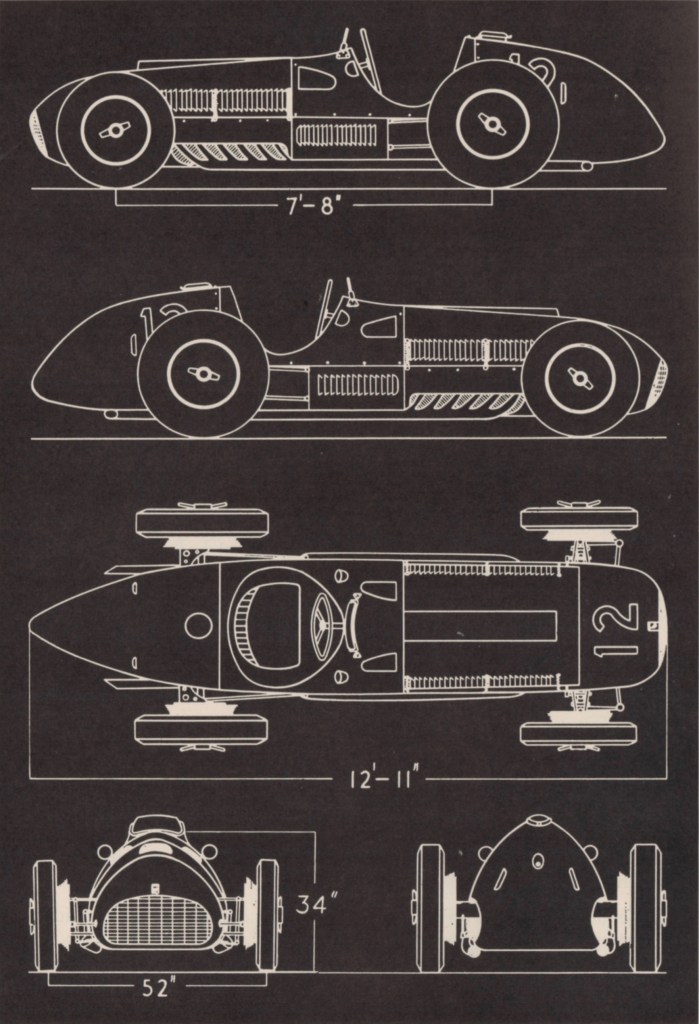

The 1951 Formula 1 twelve-cylinder Ferrari. Image by L.C. Cresswell in The Grand Prix Car Volume Two.

The Ferrari 375 Grand Prix Car. Pomeroy wrote, “One of the first tasks to which Aurelio Lampredi gave his attention in the midsummer of 1949 was the development of a new series of unsupercharged engines. He planned to fit these into the long chassis Formula II cars with de Dion rear axle for which he was also responsible….” The 375 designation, as usual, identified the displacement of a single cylinder; in this case, 375 x 12 = 4500.

A DOHC 60º V-12. “The camshaft drive,” Pom noted, “is by chain from the front end of the crankshaft, the latter running on seven Vandervell three-layer bearings which are indium plated and of 2.35 in. diameter. This type of plain bearing was first used on the smaller engines after exhaustive bench and road tests had shown that they not only had equal reliability and greater length of life but also produced an observable increase in mechanical efficiency. A similar type of bearing is used for the 1.73 in. diameter big ends and attention should perhaps be drawn to the fact that the crank pins are only 55 per cent the diameter of the cylinder bore and the bearing area must be considered as rather on the small side taking into account the size of pistons, the crank r.p.m. and the piston speed.”

This is typical of Pom’s analysis and also of his assumed level of his readership. Tomorrow in Part 2, we’ll share more of Pom’s erudite technicalities of the Ferrari 4 1/2-Litre Grand Prix car. There’ll be a personal note as well. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

Reading entries like this makes me wish I had a few more quarters and dimes in my pockets when I rode my bike some dozen miles each way to the used book stores at the west end of Colorado Avenue on weekends when I was in my early teenage years and became fascinated with cars of all racing stripes. Instead I bought early issues of Hot Road and Road&Track and hauled them home to Temple City where they joined a growing collection that lasted until my room was cleared out after college when I was swept into the military. I looked at books but they were out of my price range.