Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

ROSSUM’S UNIVERSAL ROBOTS REDUX

“ČAPEK’S ROBOTS” EXPLORED ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE here at SimanaitisSays back in September 2017. In reviewing Karel Čapek’s 1920 play R.U.R., the article asked, “Will its advancement be to mankind’s good or detriment?”

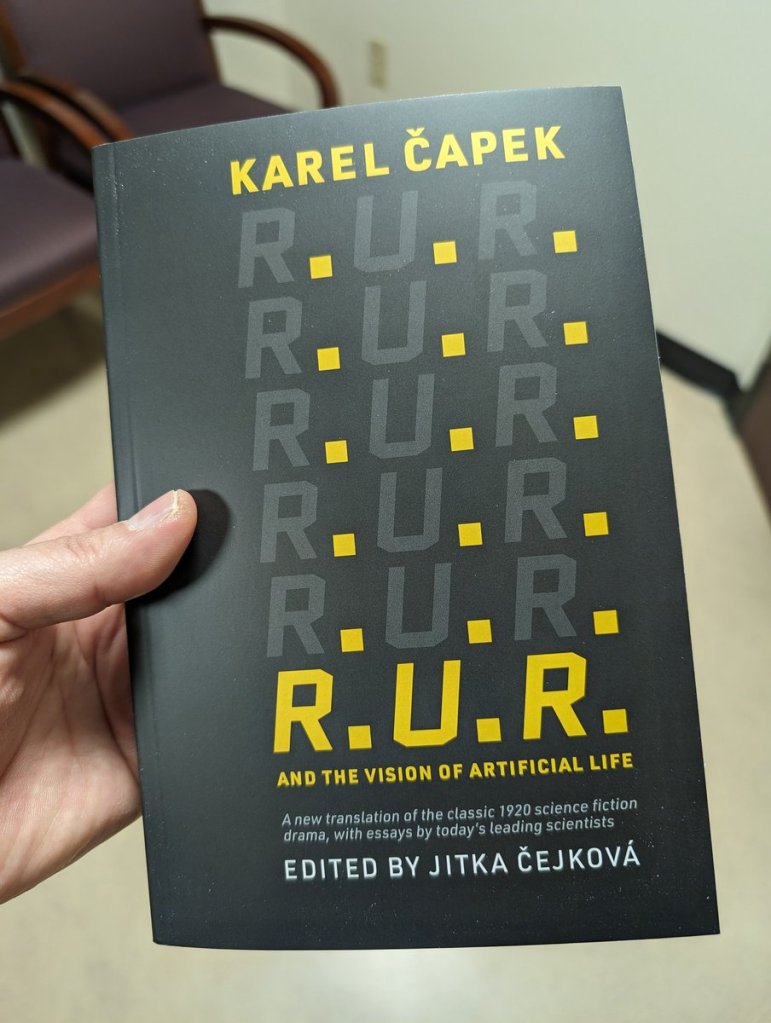

This Czech play is origin of the word “robot” and it’s also the subject of R.U.R. and the Vision of Artificial Life, a new translation as well as a collection of essays on the play’s legacy. Ed Finn reviews this work in AAAS Science, January 12, 2024. Here are tidbits gleaned from IndieBound and from this Science review.

R.U.R. and the Vision of Artificial Life, Karel Čapek author, Štĕpán Šimek translator, Jitka Čejková editor, MIT Press, 2024.

IndieBound writes, “The twenty essays in this new English edition, beautifully edited by Jitka Čejková, are selected from Robot 100, an edited collection in Czech with perspectives from 100 contemporary voices that was published in 2020 to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the play…. Throughout the book, it’s impossible to ignore Čapek’s prescience, as his century-old science fiction play raises contemporary questions with respect to robots, synthetic biology, technology, artificial life, and artificial intelligence, anticipating many of the formidable challenges we face today.”

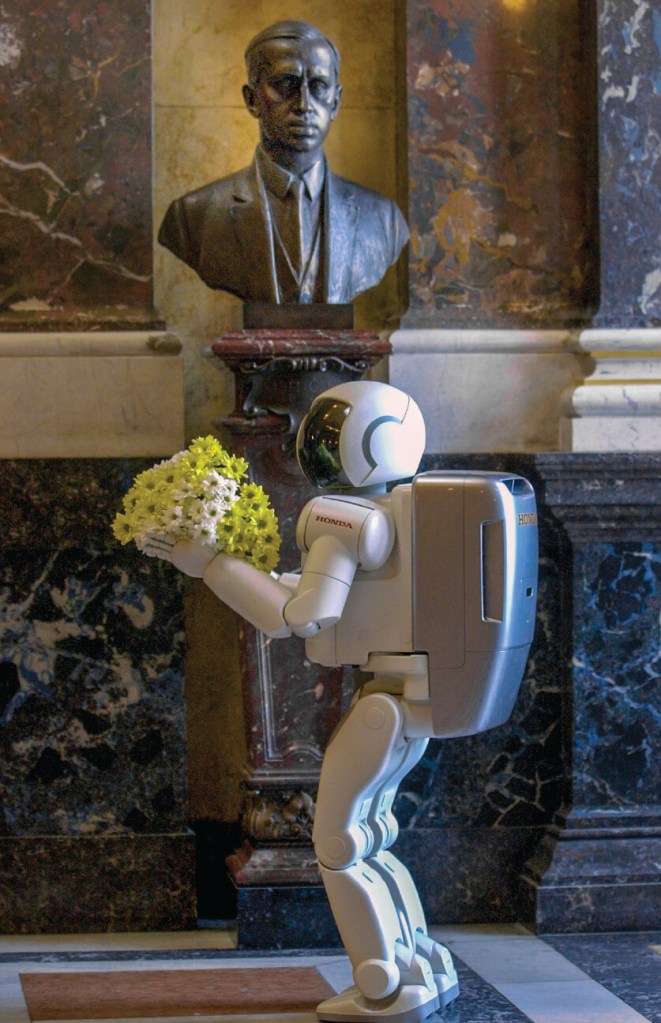

Honda robot Asimo offers flowers to the bust of playwright Karel Čapek. Image from Science, January 12, 2024.

A Complex Etymology. Science reviewer Ed Finn welcomes the work “because it reminds us that words have histories too, and we ignore them at our peril. Čapek’s neologism is an adaptation of a Czech word meaning ‘serf’ or ‘servant’ that is linked both to the service obligation that peasants would perform for feudal landowners and etymologically to Czech words for ‘woman,’ ‘child,’ and ‘orphan.’ When the robot arrived in our shared imagination of the future, it was already a form of indentured labor, a figure whose personhood is marginal, if it exists at all.”

But Indistinguishable from Humans. “R.U.R. is fascinating and bizarre,” Finn writes, “particularly for readers who might think of robots as mechanical beings plated in chrome, as they are in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis or as cybertronic machines, as they are in Isaac Asimov’s stories. As many of the essays in this volume point out, Čapek envisioned the rise of artificial life not out of silicon but synthetic biology, and the robots in his play are visually indistinguishable from humans.”

Gist of the Plot. Finn offers a precis: “Rossum’s Universal Robots is a family business built on a secret formula for creating synthetic workers. The orders keep flooding in: robots to replace human workers, robots to fight wars, robots to replace the humans killed in the wars. Meanwhile, human fertility plunges to zero. Predictably, the robots throw off their chains and erase humanity from the Earth. The play ends as strangely as it begins, with two robots departing like Adam and Eve, offering up the promise of new life from the ashes of humanity’s destructive ambition.”

“The blithe executives of R.U.R.,” Finn recounts, “sound exactly like tech evangelists today, predicting the end of work and an age of abundance. The humans acquit themselves poorly, of course, blinded by greed and badly constructed moral frameworks.”

Ultimately. Finn writes, “Čapek’s masterpiece reminds us first that just because we can does not mean we should. But he also tells us what we must do: care for our creations and for one another and take responsibility for the full consequences of our technological dreams.”

Heady thoughts, these, and most appropriate for our times. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2024

Some 70 or so years later I remain amazed my fifth grade teacher was prescient, well read and knowledgeable enough to read RUR to us and have us discuss it at Longden Avenue Elementary School in Temple City, CA. Wherever you are, Miss Frank, bless you and your memory.