Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

HOKUSAI JUST UP THE STREET

I’VE LONG ADMIRED THE ART OF HOKUSAI, thus Daughter Suz and I were delighted to have an exhibit of international stature nearby at the Bowers Museum.

“Beyond the Great Wave: Works by Hokusai from the British Museum” continues through January 7, 2024, with special events planned next month: There’s a Narrative in the Art of Hokusai with Hollis Goodall on January 6, 2024, 1:30 p.m.–2:30 p.m. as well as half-hour Closing Day Gallery Tours on January 7, 2024, at 11:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 2:00 p.m. These are free for exhibition attendees. Admission is $28/$25/$10 for adults/seniors and students/accompanied children, respectively.

Hokusai: Ukiyo-e Master. Wikipedia recounts, “Hokusai was instrumental in developing ukiyo-e from a style of portraiture largely focused on courtesans and actors into a much broader style of art that focused on landscapes, plants, and animals. His works are thought to have had a significant influence on Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet during the wave of Japonisme that spread across Europe in the late 19th century.”

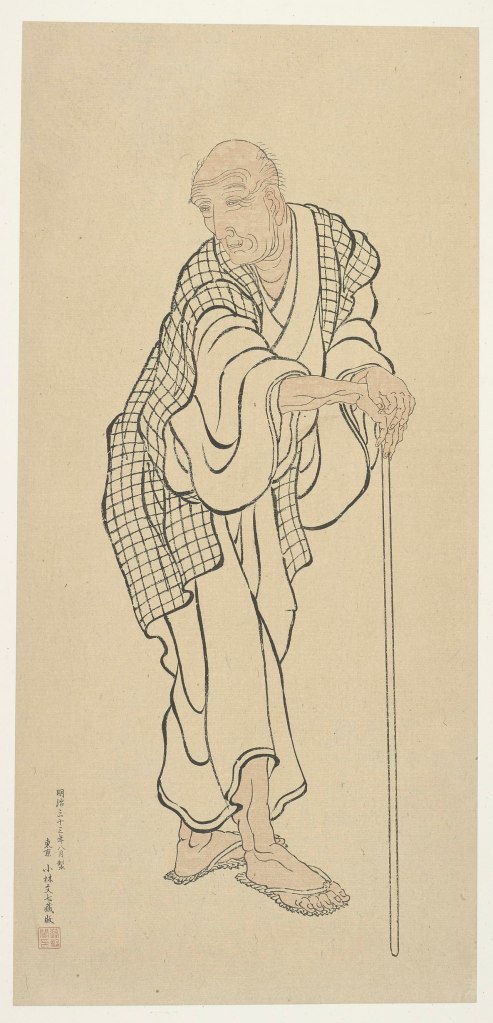

Katsushika Hokusai, 1760–1849, Japanese painter and printmaker extraordinaire. Self-portrait at the age of eighty-three from Wikipedia.

“Hokusai began painting around the age of six,” Wikipedia says, “perhaps learning from his father [a mirror-maker for the shogun], whose work included the painting of designs around mirrors…. At 14, he worked as an apprentice to a woodcarver, until the age of 18 when he entered the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō. Shunshō was an artist of ukiyo-e, a style of woodblock prints and paintings that Hokusai would master.”

Wikipedia continues, “Upon the death of Shunshō in 1793, Hokusai began exploring other styles of art, including European styles he was exposed to through French and Dutch copper engravings he was able to acquire.” This, despite Japan’s relative isolation at the time.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai’s most celebrated work, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, includes The Great Wave off Kanagawa. As many as 8000 impressions of this design were printed. So popular was the series that later editions added ten more views.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, woodblock print, 10.1 x 14.9 in., late 1831.

Ukiyo-e, literally “pictures of the floating world,” were widely available to many Japanese of the Edo era. British Museum scientist Capucine Korenberg notes that “a woodblock print could be had for the price of “a double helping of soba noodles.”

An Intricate Process. Though mass-produced in series of thousands, these woodblock prints were anything but simple in their production. First, a painting would be reproduced, the number of copies determined by its number of separate colors. Then each of these images would be transformed onto a block typically of cherrywood.

These blocks would then be intricately carved in the negative, with regions of that particular color raised in relief. Last, polychrome prints might require as many as 20 separate blocks, with alignment absolutely crucial for proper registration of the colors. Eventually after thousands of reproductions, blocks would require replacement.

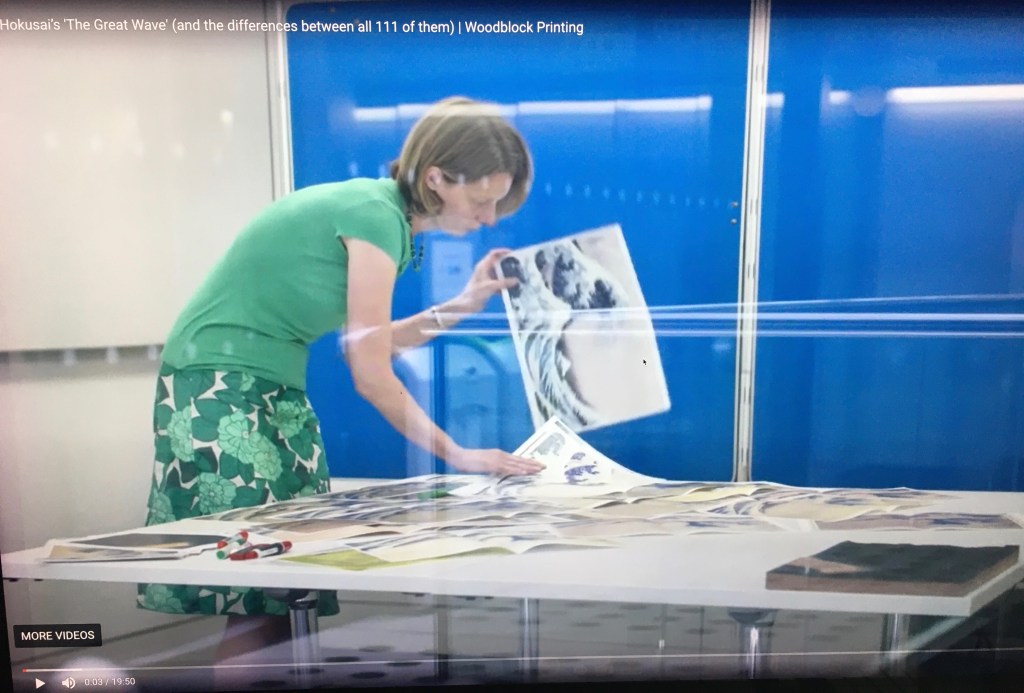

Capucine Korenberg analyzes several Great Wave woodblock sets of 113 extant. Image from YouTube.

The Bowers exhibit has a brief video showing Korenberg at work with a selection of carving tools. I was amazed at the minute crafting, given the typical size of a woodblock print. The Great Wave off Kanagawa, for example, is about 10.1 x 14.9 in. Others in the Bowers exhibition were considerably smaller with even more detail.

Our Favorites. Daughter Suz particularly admired the rendering of water in Travellers Crossing the Oi River. Hokusai’s use of Prussian blue is abundant here and in The Great Wave. It’s likely the artist dealt with Dutch smugglers to get this rich hue.

Travellers Crossing the Oi River, woodblock print by Hokusai, 14 x 18 in., one of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, about 1833.

There was no bridge nearby; people and goods were transported through the Oi torrents on shoulders. As something of an inside joke, the large green box and two packs are marked with the trademark of Nishimuraya, the series publisher.

I particularly like Fujimigahara (“Fuji-view Fields”) in Owari Province. An artisan is intent on sealing the seams of a huge tub.

Fujimigahara (“Fuji-view Fields”) in Owari Province, woodblock print, 8.3 x 12.6 in., late 1831.

The artisan seemingly ignores the beauty of Mount Fuji, though seams of the tub direct one’s eye to the far-off view.

Hokusai’s Ambition. I came away from the Bowers exhibition even more awed by Hokusai’s talents in painting and printmaking. And also his evident managerial ken (as no one person could have produced all this in a lifetime).

Indeed, Hokusai’s last words at age eighty-eight are variously quoted. One version is “If heaven will afford me five more years of life, then I’ll manage to become a true artist.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023

Insightful last words that should be taken to heart by any craftsman, wordsmith or scholar of all disciplines.

We were among the first American families to be stationed in Japan in late ’46, and my artist mother studied the fastidious skills required to print the many print blocks. We treasure a few of the best examples we purchased … all done by original processes … not modern presses.

The most revered are the original pressings, supervised or done by the original artist. Those wood blocks are carefully preserved in appropriate temperature and humidity controlled conditions, and occasionally used to produce very limited authorized editions, identified by special stamps and kanji on the margins or back.

During my Naval service, someone did a replica of the honored The Great Wave off Kanagawa with an appropriately sized and rendered US aircraft carrier sailing in the trough of the wave.

The caption read: “Yeoman … notify the Skipper that we’ve entered the Sea of Japan!”