Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

ALPHABETS, SYMBOLS, AND OTHER SQUIGGLY STUFF

ONE OF MY MORNING RITUALS, after 6:00 a.m. Pacific BBC World Service and a final reading/editing of the day’s SimanaitisSays, is Voice of America News. Each day VOA includes its “Language Services,” a scanned lists of items selected from its 47 languages other than native English. Many, including Deewa, Persian, and Urdu are shown in what appears to be Arabic. Russian, Macedonian, and Ukrainian use Cyrillic characters. A goodly number, including Albanian, Swahili, and Turkish, use our familiar Roman alphabet. Others, Armenian, Bangla, and Burmese among them, sure look like unique character sets.

Having this admittedly superficial knowledge of foreign character sets, I found interest in reading Andrew Robinson’s “Writing Without Words,” Science, October 26, 2023, a review of Richard Sproat’s book on the subject.

Symbols: An Evolutionary History from the Stone Age to the Future, by Richard Sproat, Springer, 2023.

IndieBound notes that “Richard Sproat is a Senior Staff Research Scientist at Google, Japan, working on Deep Learning for applications in speech and language processing. He attended the University of California, San Diego and then MIT, where he received his Ph.D. in Linguistics in 1985. He has published widely in various areas of linguistics and computational linguistics, and he has a particular interest in writing systems and symbol systems.”

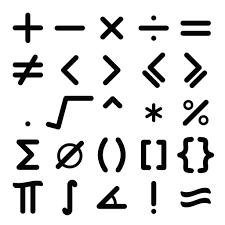

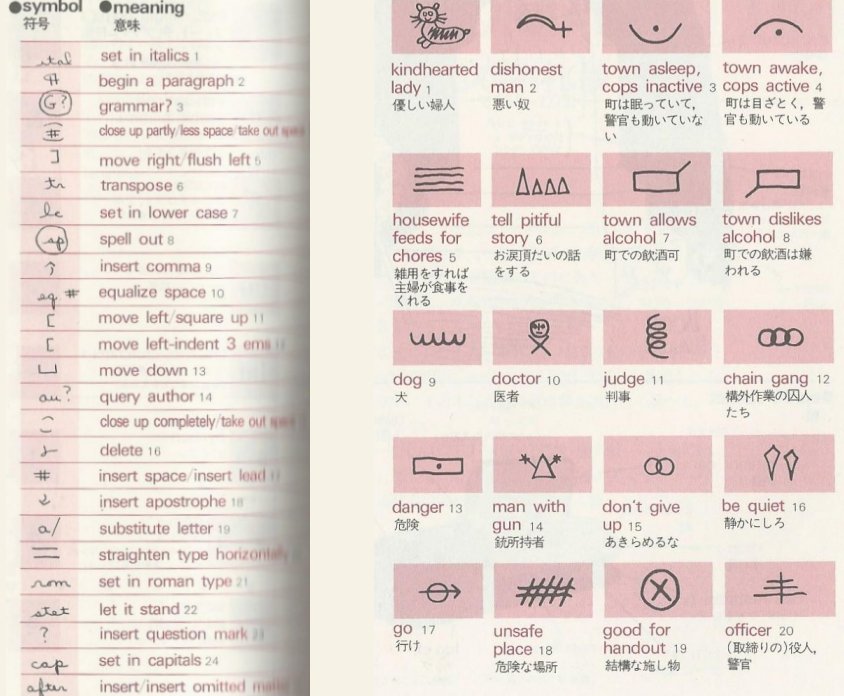

Inclusivists Versus Exclusivists. Inclusivists, Robinson recounts, “classify as writing all systems of graphic symbols that can convey ‘some amount of thought’ without using phoneticism. Examples include mathematical symbols, musical notation, and emoji.”

“Meanwhile,” Robinson says, “ ‘exclusivists’ reject such systems and limit writing to symbols that can convey ‘any and all thought.’ Mesopotamian cuneiform, European alphabets, and Chinese characters, all of which are dependent on phoneticism, meet exclusivists’ criteria.” By the way, Robinson notes that author Sproat is an exclusivist.

Emojis, fine with inclusivists, not with exclusivists. Image from parade.com.

Which Came First: Civilization or Writing? Robinson describes, “What is clear is that civilization preceded writing. In Sproat’s shrewd words, ‘Writing is the product of civilization, but it is not a necessary product of civilization.’ We know this from archaeological excavation of Mesopotamian cities—Uruk, for example—that surely required some bureaucracy in order to flourish, which they did before they had access to writing.”

“The earliest known writing certainly dates from Mesopotamia, ~3300 BCE,” Robinson says, “but whether this influenced through diffusion the invention of later Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese characters, and Mesoamerican scripts remains unclear.”

What of the Future? Robinson concludes his review: “As for the futuristic vision of a ‘universal’ writing system in which symbols convey ‘any and all thought’ independent of the world’s spoken languages—a proposal first advocated by philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz in the 17th century—this will remain a dream, according to Sproat. ‘Language is still our most versatile form of communication,’ he writes, ‘and unless Elon Musk’s prediction that his Neuralink implants will make language and speech obsolete comes true, it seems destined to remain that way.’ ”

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz, 1646–1716, German polymath extraordinaire.

Imagine that: co-developer of the Calculus Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz and X formerly known as Twitter’s Elon Musk in the same paragraph. This in itself is thought-provoking. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023