Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

TIDBITS FROM SETRIGHT’S TIMESCALE PART 1

AUTOMOTIVE JOURNALISTS WRITE ABOUT AUTOMOBLES. But some, like L.J.K. Setright, widened their field of vision considerably. His classic Drive On! is accurately subtitled A Social History of the Motor Car.

Drive On! A Social History of the Motor Car, by L.J.K. Setright, Granta, 2002.

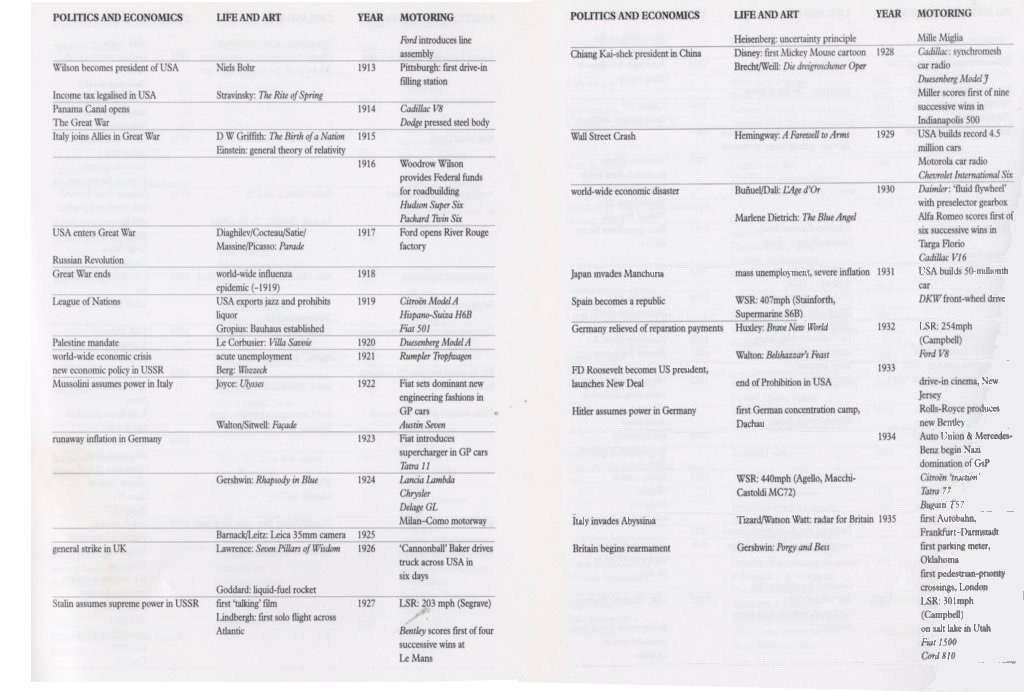

The book’s eight-page “Timescale” is arranged by matters of politics and economics, life and art, and motoring from 1800 through 2000. Here are tidbits gleaned from Setright’s considerable breadth of interests.

1800-1912. This and following images from Drive On!

Napoleon, Lenoir, Ziegfeld, and Zeppelin. I hadn’t realized that Trevithick’s steam carriage coincided with Napoleon’s efforts to control Europe. Or that Lenoir’s coal-gas engine was contemporaneous with our Civil War.

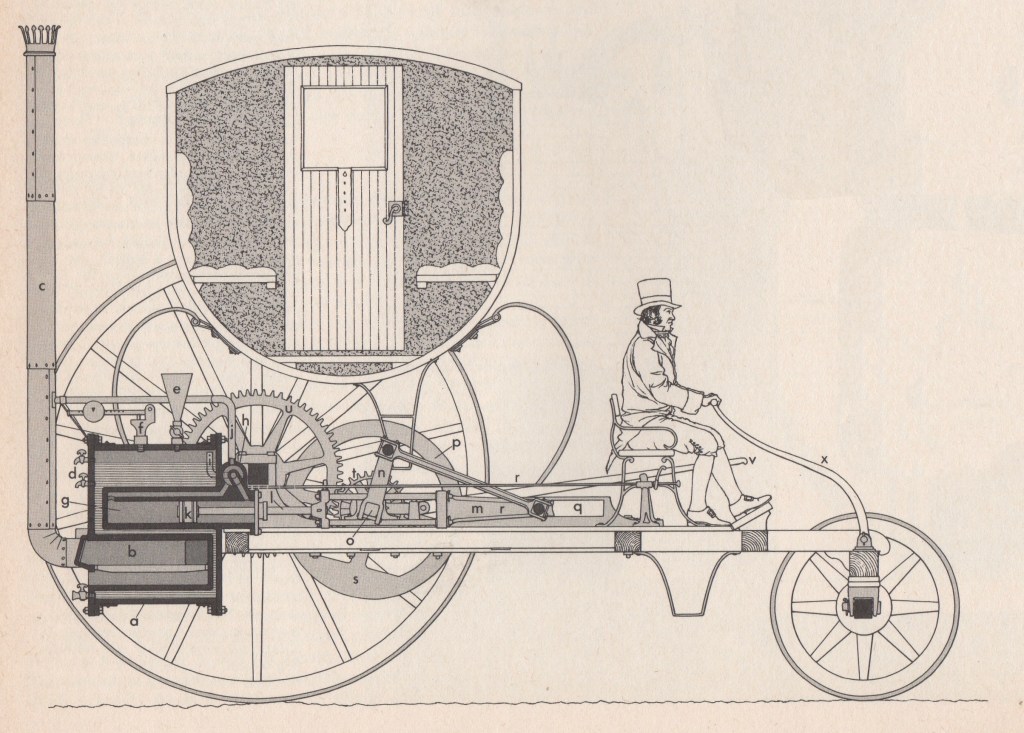

Richard Trevithick’s Steam Carriage. Image from A History of the Machine.

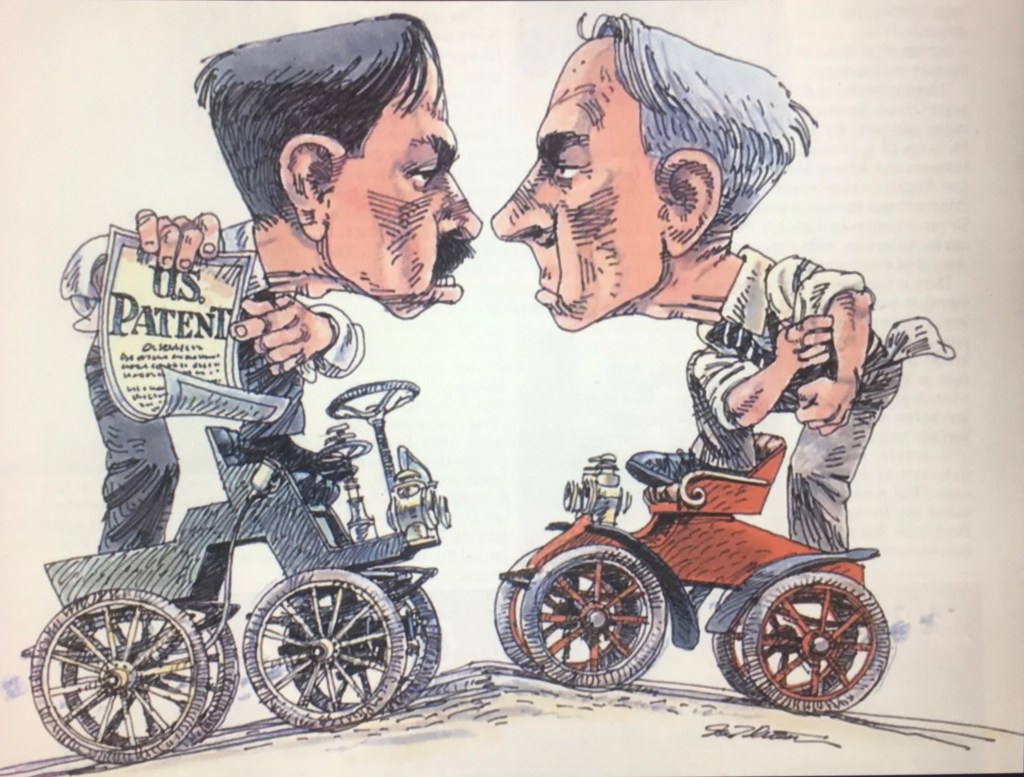

George B. Selden received his 1879 patent for the automobile only 26 years after Commodore Matthew Perry’s Black Ships forced Japan out of its 300-year Tokugawa isolation.

This wonderful illustration is by Jon Dahlstrom. It accompanied an article on the topic in Road & Track, December 2003.

Selden and Henry Ford really got into it in 1903, their court battle ending in 1911 in Ford’s favor. Setright notes that the Ziegfeld Follies, the Hoover vacuum cleaner, and Zeppelin’s first passenger service arrived in this era as well.

1913-1935.

Paris Rioting, Pittsburgh Fillups, Marlene’s Angel, Vincenzo’s Targa. Setright certainly selected variety for the year 1913: “Income tax legalized in USA, Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring, Pittsburgh: first drive-in filling station.” Stravinsky’s “jagged rhythms, crunching discord, and strange jerking” caused a riot in its Paris premiere.

Dancers in Nicholas Roerich’s original Rite of Spring costumes. Image from Wikipedia.

It wasn’t long before gas stations had car washes (quite independently of the Paris goings-on).

Setright cites Buñuel/Dali’s L’Age d’Or and Marlene Dietrich’s The Blue Angel as Life and Art in 1930, the same year that he includes Alfa’s first of six successive wins in the Targa Florio.

I suspect Vincenzo Florio may still be spinning in his grave after Pirelli’s highjinks at its 1995 introduction of the P7000 Supersport.

Thanks, Bob Newman and Jack Gerken (Pirelli’s P.R. guy and agency rep, respectively)—and good friends.

We’ll continue with L.J.K. Setright’s Timescale in Part 2 tomorrow, 1936 through 2000. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023

Setright was brilliant, for thinking autoholics, encompassing, as described below, “politics and economics, life and art, and motoring from 1800 through 2000.”

Most gearheads today live in a one-marque-itis vacuum. Today’s auto scribes deliver only thrice-told tales with glossy pictures — tool catalogues with a few lines of breathless gush — can tell you how a car was made, but not w h y.

Thank you!