Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

VIEWED RECENTLY, REVIEWED BACK THEN

BEING AS I AM an aficionado of old movies, I thought it would be interesting to consult reviewers of the era, kinda to see if they got it right. My source in this regard is Dargis and Scott’s wonderful compendium The New York Times Book of Movies.

The New York Times Book of Movies, selected by Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott, edited by Wallace Schroeder, Universe, 2019.

Here are tidbits gleaned from this source, together with comments based on my Turner Classic Movies viewings.

The Lady Vanishes, 1938. This Hitchcock mystery thriller caught Hollywood attention and the British-bred director soon moved to the U.S. Wikipedia describes “the film is about a beautiful English tourist travelling by train in continental Europe who discovers that her elderly travelling companion seems to have disappeared from the train. After her fellow passengers deny ever having seen the elderly lady, the young woman is helped by a young musicologist, the two proceeding to search the train for clues to the old lady’s disappearance.”

Even watching it more than once, I love the way Hitchcock sprinkles clues throughout the action.

As quoted in The New York Times Book of Movies, reviewer Frank S. Nugent wrote on December 26, 1938: “If it were not so brilliant a melodrama, we should class it as a brilliant comedy…. When your sides are not aching from laughter your brain is throbbing in its attempts to outguess the director.”

“There isn’t an incident,” Nugent wrote, “be it as trivial as an old woman’s chatter about her favorite brand of tea, that hasn’t pertinent bearing on the plot. Everything that happens is a clue.”

“And having given you fair warning, we still defy you to outguess that rotund spider, Hitch. The man is diabolical; his film is devilishly clever.”

Nugent sure got that right.

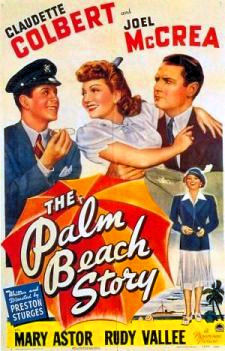

The Palm Beach Story, 1942. This madcap Preston Sturges flick has already appeared here at SimanaitisSays. Wikipedia sets the stage: “Inventor Tom Jeffers and his wife Gerry are down on their luck financially. Married for five years, the couple is still waiting for Tom’s success. Anxious for the finer things in a life, Gerry decides that they both would be better off if they split.…”

Portrayed by Claudette Colbert, Gerry takes the train for Palm Beach and a new start. Chaos ensues and she is rescued by “meek, eccentric, amiable, and bespectacled John D. Hackensacker III (played by Rudy Vallée), who immediately falls for her.”

Husband Tom, portrayed by Joel McCrea, arrives in Palm Beach and mixes it up with Hackensaker’s ultra-rich set. I enjoy every Sturges quick-action madcap minute of it.

By contrast, Bosley Crowther was less amused in his December 11, 1942, review: “It’s a shame,” Crowther wrote, “that Preston Sturges the writer and Preston Sturges the director of loco films didn’t get a little better acquainted before they—or, collectively, he—put the final and finishing touches on The Palm Beach Story.”

“As a consequence,” Crowther said, “Except for some helter-skelter moments, it is generally slow and garrulous…. It should have been a breathless comedy. But only the actors are breathless—and that from talking too much.”

I beg to differ. And, irrelevant though it is, I note that I was less than two months old when Crowther’s review was published.

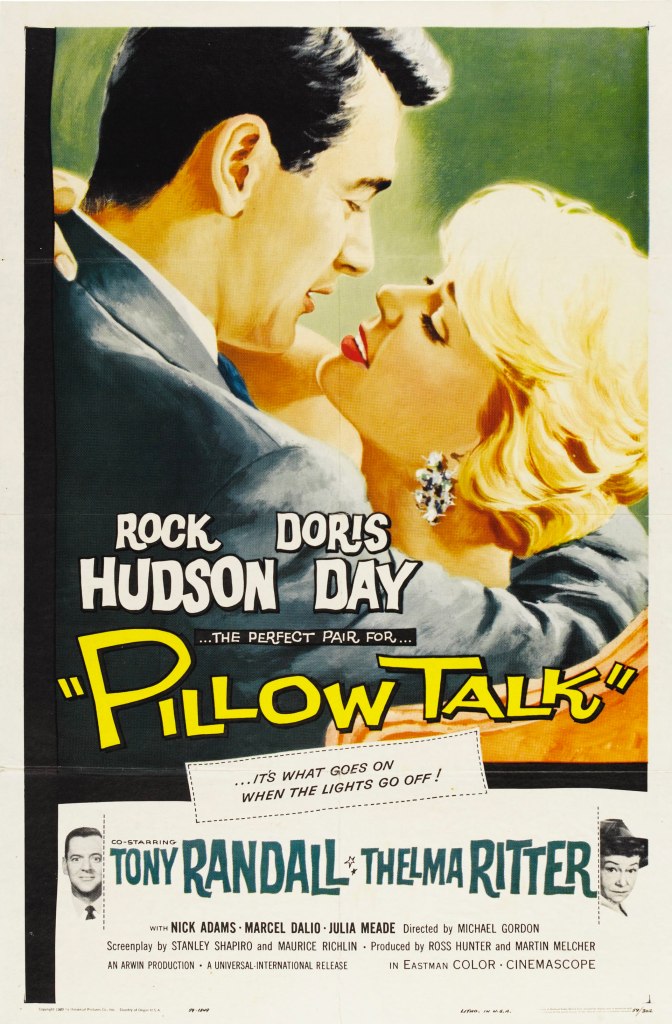

Pillow Talk, 1959. Wikipedia summarizes the flick as telling “the story of Jan Morrow (Doris Day), an interior decorator and Brad Allen (Rock Hudson), a womanizing composer and bachelor, who share a telephone party line.”

Those of us of a certain age recall the hassle of party lines; those to whom cell phones have always been ubiquitous might be baffled by the premise.

The flick is in CinemaScope and even its TV rendering is bright and colorful. Daughter Suz was impressed by Doris Day’s Jean Louis attire. We both enjoyed Thelma Ritter’s Alma, Morrow’s housekeeper, and Tony Randall being part of the comedic ensemble.

Bosley Crowther wrote in October 7, 1959, “A nice, old-fashioned device of the theater, the telephone party line, serves as a quaint convenience to bring together Rock Hudson and Doris Day in what must be cheerfully acknowledged one of the most lively and up-to-date comedy-romances of the year.”

However, I must note, elements of Pillow Talk are firmly lodged in the Fifties and in poor taste these days, especially reflecting Hudson having been one of the first celebrities to die of AIDS.

“Color and some likeable music,” Crowther wrote, “brighten this pretty film, which has a splendid montage of New York in it.”

Wikipedia notes that in 2009, Pillow Talk “was entered into the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being ‘culturally, historically or aesthetically’ significant and preserved.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023