Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

JANE’S ART PART 2

YESTERDAY, TIDBITS FOCUSED ON SEVERAL ADS from Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1919. Today in Part 2, we enjoy the high level of technical illustration in this particular Jane’s.

Attributions. Fred T. Jane himself had been known as a talented illustrator, but alas he had died at the age of 50 in 1916. Several of the 1919 illustrations cite German origins. Others tantalize with a tiny LB icon, which I’m guessing is Leonard Bridgeman (1895-1980), who had worked with editor CG Grey at Aeroplane and joined him on the staff of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft in 1923.

A neat Bridgeman tidbit: His first aviation assignment was in 1913 when he was 18. One of his drawings was used to illustrate the Hendon Air Race program. As payment, he got a ride in a 70-hp Maurice Farman biplane. Quite the deal, I say.

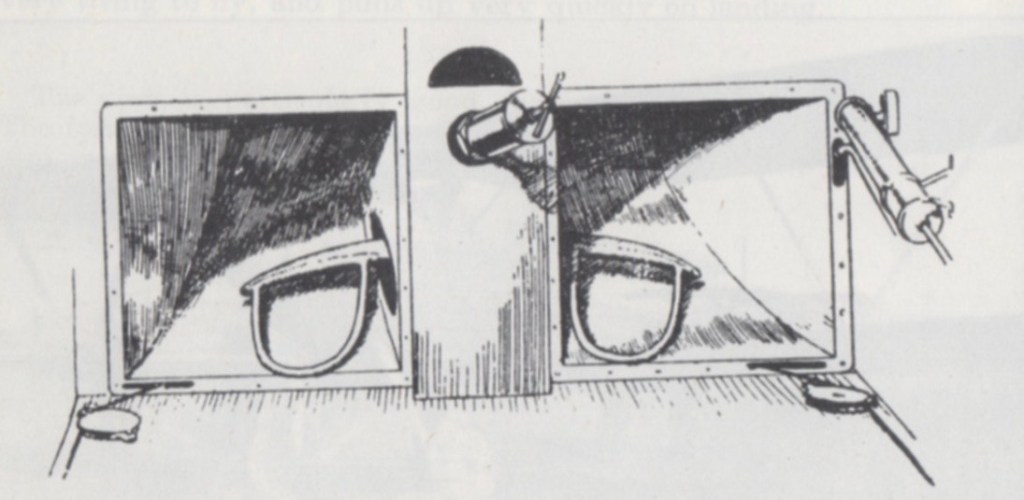

Cradles, Lever, Wheel, and a Cloche. “The Pilot’s View” recounted that The Wright Flyer used a hip cradle for roll and yaw and a lever for pitch. Glenn Curtiss’s Reims Racer had a shoulder harness for roll and an oversize wood-rimmed steering wheel, its rotation controlling the rudder, its fore/aft motion controlling the elevators. The nearest thing to a classic control stick was Blériot’s “cloche,” a non-turning wheel that was gripped for pivoting fore/aft for pitch and laterally for roll.

Variations on the Control Stick Theme. As noted here at SimanaitisSays, French aircraft and engine builder Robert Esnault-Pelterie invented the joystick as a single integrated flight control. After World War I, he defended his patent on the idea; eventually royalties from the joystick made him wealthy.

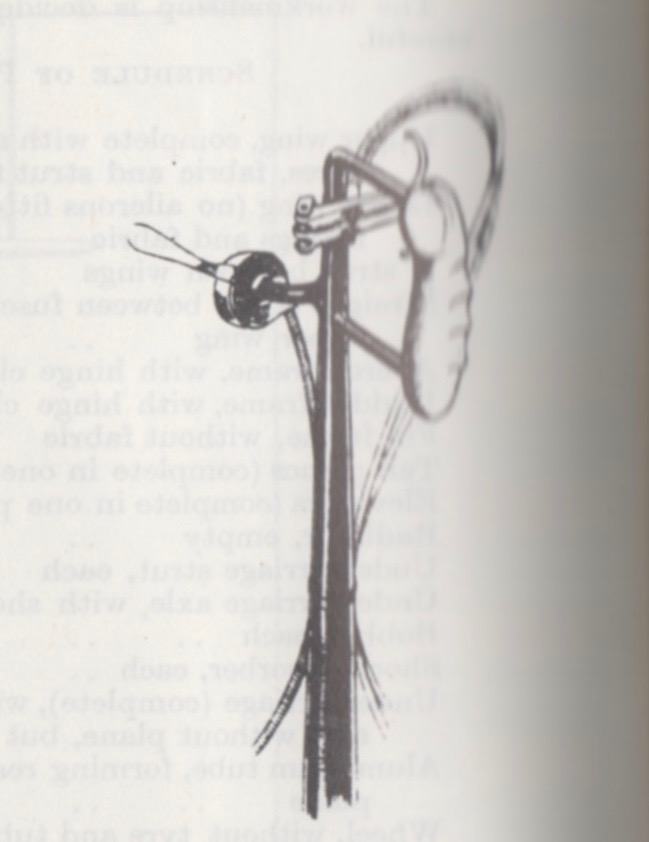

Inverted horns seemed to be something of a fashion with control sticks.

Nor was the steering wheel completely ignored.

The B.A.T. and the 1913 Deperdussin Monoplane. Chief Designer Frederick Koolhaven of the British Aerial Transport Company also had a hand in the 1913 Deperdussin Monoplane, “the first machine to cover 120 miles in an hour,” noted Jane’s.

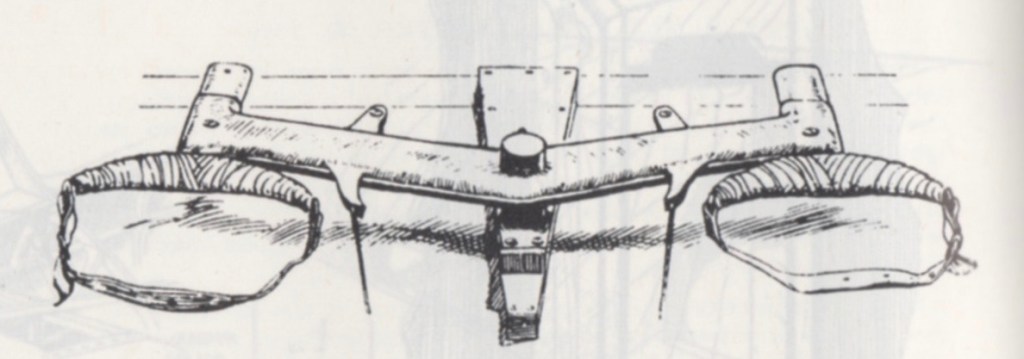

And For The Feet. The simplest rudder control was a single bar, possibly of wood and perhaps notched for shoe grip. Seemingly, though, designers got positively artful about pedals.

Likewise for Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1919: It had artful documentation as well. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023