Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

THE JAPAN YEAR BOOK 1918

NATIONAL “YEAR BOOKS” AREN’T THE SORT OF THING that a tourist totes around. Instead, they’re compendia identifying a country’s territory, its government, its people, its commerce, its general goings-on for the year. The year 1918 was a pivotal one, marking the end of “the war to end all wars.” And Japan was an interesting country: Just 60 years past its forced opening to the rest of the world, Japan’s Taishō Democracy had replaced the Meiji Era in which the country enthusiastically assimilated Western ways, both good and bad.

And, wouldn’t you know, in 1989 I came upon a fine copy of this book not in Japan, but in Daytona Beach, Florida. Such are the vagaries of book hunting.

Tidbits, 1918. The Japan Year Book’s detailed Index offers productive tidbit gleaning ranging from ABT SYSTEM (“Japanese railways are much behind those in Europe or America.”) to Zinc (“This is quite a revolution, for Japan was formerly an ore-exporting and metal-importing country as regards this metal.”).

Also, “Motor-car Corps and Subsidy” describes, “In May 1918, law for granting bounty to motors strong enough for purposes of transportation in time of need was enacted…. It is said that at present there will be only ten cars or so throughout the land qualified to receive the bounty.” There’s no mention whatsoever of private motorcars.

Aviation. Similarly, “Aviation by civilians is still a thing of the future in Japan. There are some 20 airmen who have got training, most of them abroad, and eight of whom have been allowed to join the French military aviation service. With few exceptions the rest may be said yet leading the life of martyrs.”

“With no regular means of support,” The Japan Year Book continues, “they can hardly maintain themselves as aviators, for they have no machines good enough for public performances, the machines being poor things of only 50 or 60 h.p. that have become a byword from repeated failures. Some of the airmen have been obliged, therefore, to turn chuffeurs [sic] as means of livelihood.”

By the way, these previous two paragraphs reappear, to a great extent word for word, in Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft 1919.

See also Baron Asahi Mirahara’s “Aircraft in Japan, 1910–1945.” Perhaps it’s his father Baron Jiro Miyahara included in The Japan Year Book’s “Who’s Who in Japan.”

The Great War. Mr. Takenob, of the J.Y.B. Office, writes in its Preface, “The War has proved quite unexpectedly beneficial to Japan’s industries, shipping, trade and finance. The fact is, in spite of the best wishes of Japan to render her utmost in pushing with the Allies the common cause of punishing the German militarism, her geographical position practically restricts her operation to sea, as far as the European field of operation is concerned.”

The Great War Activities. The Japan Year Book’s Diary recounts that on July 19, 1917, “A Japanese Squadron arrives in the Mediterranean to co-operate with the Allies.” On July 26, “The Japanese warships in the Mediterranean sinks [sic] a German submarine.”

On January 9, 1918, “King George of Great Britain presents the Emperor with the title of British field marshal.” On April 15, “An American-Japanese Agreement relating to the chartering of Japanese vessels to the U.S. is signed.” On May 18, “The Sino-Japanese Military Agreement is duly concluded.” On June 12, “Dr. Sun-yatsen visits Japan with Mr. Hu-Han-min and others.” On June 18, “Prince Arthur of Connaught arrives in Tokyo on behalf of King George to present the baton of a British Field Marshal to the Emperor.”

Yes, But Also…. Yet, as Wikipedia notes, “The early 20th century saw a period of Taishō democracy (1912–1926) overshadowed by increasing expansionism and militarization. World War I allowed Japan, which joined the side of the victorious Allies, to capture German possessions in the Pacific and in China.”

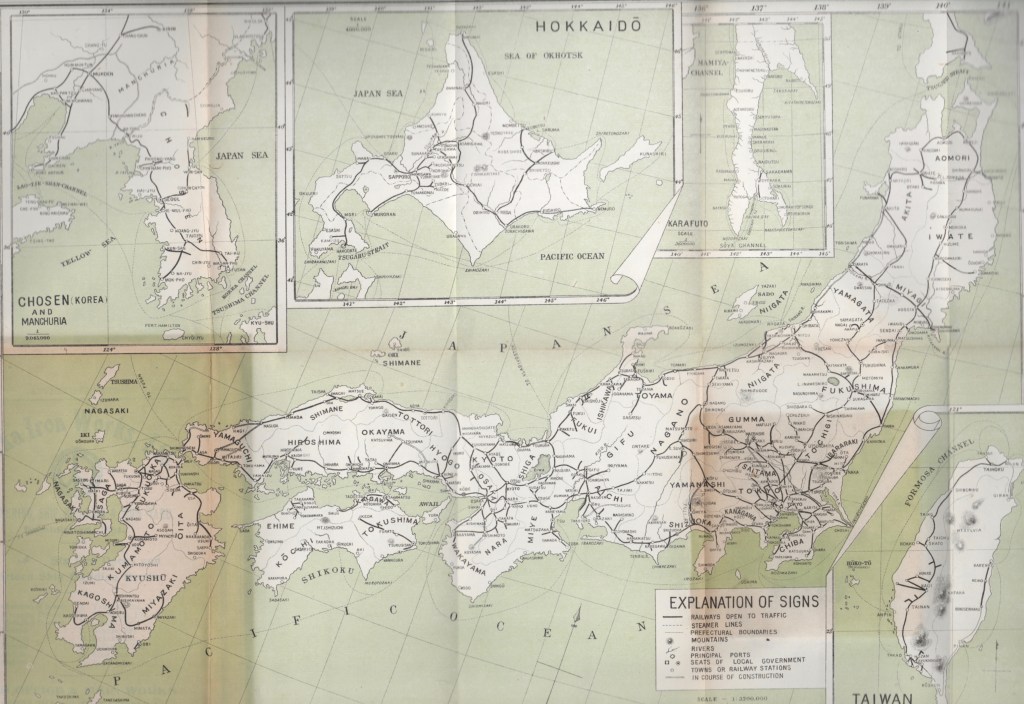

“History”? In Appendix D. Japan and the European War, pgs 757–770, The Japan Year Book gives details of these and other Great War interactions, though not without nationalistic jargon. For example, Chapter XXXV, pgs 682–700, describes the “annexation” of Chosen (Korea).

Chapter XXXVI, pgs 701–712, Taiwan (Formosa) ends with this chilling bit of pseudohistory: “The 1915 affair originated chiefly from superstition of ignorant natives who were silly enough to put credence in the wild story of some ringleaders that they could easily create storms by means of the special charms they possessed and expel the Japanese with the aid of Chinese troops, and that the faithful upholders of the movement would be amply rewarded with the land now owned by the Japanese. In the summer of the year the plot was discovered and arrests began.”

Not the guidebook that tourists would tote around, but compelling accounts of a country’s devolution into the Shōwa era’s Empire of Japan, 1926–1945, the country’s defeat in World War II, and its evolution into the State of Japan, 1945 to today. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023

Related

Information

This entry was posted on August 2, 2023 by simanaitissays in Just Trippin' and tagged "The Japan Year Book 1918" biased views on Taiwan and Korea, "The Japan Year Book 1918" Y. Takenob, Baron Jiro Miyahara "Who's Who Japan 1918", English King George appoints Japanese emperor as Field Marshal (baton delivered), Japan 1918: Korea and Taiwan included, Japan an ally of The Allies in World War I, Japan's few aviators had less than reliable equipment, Japan's railway system inferior to Europe's or America's in 1918.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-gklCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012